Whether people are baseball fanatics or just Brad Pitt fans, they’ve most likely seen the film Moneyball. It’s based on the true story of the Oakland A’s, a Major League Baseball team that changed sport recruitment by using statistics to scout talent, choose players, and establish a winning team. But it takes more than statistics to build a successful team. It takes careful integration of players’ skills and personalities. Learn more in the SIRC blog.

Sport organizations produce more data than most organizations, ranging from athlete training and performance tracking to memberships and participation data. But how often is this data used to inform decision-making? Learn more about how Row Ontario is using existing data to inform decisions that will help to grow the sport in the SIRC Blog.

Technology can help coaches with decision-making, but actually getting the necessary data may be unreasonably cumbersome. When evaluating whether a technology is appropriate for your needs, ask for a trial. Trials can help coaches discover if they can access the necessary information and evaluate whether the technology meets their needs.

With limited resources for research initiatives, partnering with external research or community groups can increase a sport organization’s capacity to conduct concussion injury prevention work. Developing initiatives with these partners, such as universities and hospitals, can help sport organizations gain access to trained staff capable of taking on some of the research burden.

Over the past 6 months, we’ve seen ongoing news of alleged maltreatment of athletes who compete at national and international levels. These reports of maltreatment in artistic swimming, gymnastics, bobsleigh and skeleton, and most recently boxing have sparked increased discussion by both the sport sector and the public. These reports also led to action by the Government of Canada and countless calls to meaningfully engage stakeholders, specifically athletes, to collaboratively evolve the sport system for the better.

Sport administrators are working in earnest to ensure that sport is safe, welcoming and inclusive. They’re working to that end despite facing heightened demands in terms of increased mandates, podium expectations, stagnant funding, dropping participation rates and intensified public scrutiny. To make positive changes, we must understand our organizational environments and the needs and interests of our stakeholders. Program evaluation and analysis methods are traditionally used by sport and recreation organizations to gain this understanding. However, real-world data and real-world evidence offer another format for understanding the environment and responding to these needs.

Applying real-world data to sport

The health sector has begun to use real-world data (RWD) to inform its practices. RWD is an umbrella term for healthcare data collected from various sources in the routine delivery of care, as opposed to what’s collected from strictly conventional randomized control trials (Birkmeyer, 2021; Makady et al., 2017). These RWD sources include patient, clinical and hospital data, public health and social data, and others (Makady et al., 2017). By looking across these data sources, they can use analytics to transform that aggregated data into real-world evidence (RWE) through analytics. In turn, that results in rich and holistic insights that can be used to inform changes in policy and make meaningful decisions about daily practice (Birkmeyer, 2021).

The health sector has begun to use real-world data (RWD) to inform its practices. RWD is an umbrella term for healthcare data collected from various sources in the routine delivery of care, as opposed to what’s collected from strictly conventional randomized control trials (Birkmeyer, 2021; Makady et al., 2017). These RWD sources include patient, clinical and hospital data, public health and social data, and others (Makady et al., 2017). By looking across these data sources, they can use analytics to transform that aggregated data into real-world evidence (RWE) through analytics. In turn, that results in rich and holistic insights that can be used to inform changes in policy and make meaningful decisions about daily practice (Birkmeyer, 2021).

Sport organizers have traditionally used demographics, registration and retention data to inform decision making. They’ve also conducted formal evaluations after finishing programs and events. Although this information is useful, analysis can take considerable time. Plus, the analysis may only happen annually or at a few key points throughout the year, such as between seasons of play. To this end, the concepts of RWD and RWE offer a different perspective in how the sport sector could interpret data and respond to stakeholders’ needs and trends. Incorporating new and different types of data into analysis could allow sport organizers to bridge the real-world experience of stakeholders and respond in real time.

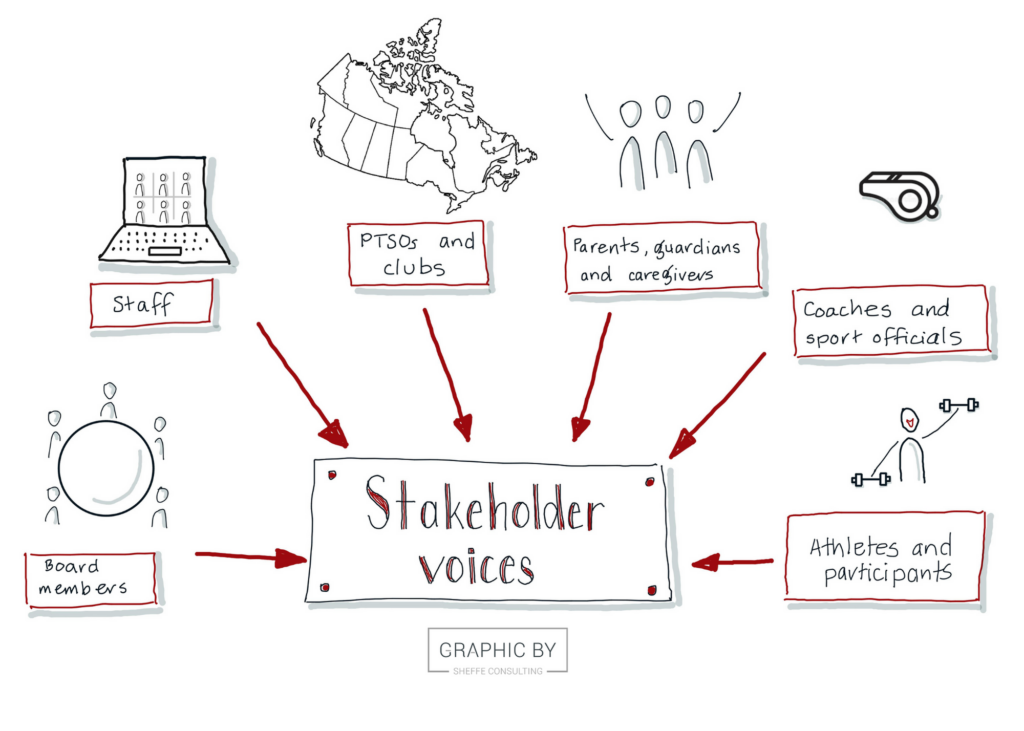

Stakeholder engagement is one RWD source that could present sport organizers a fuller picture of their organization. Stakeholder engagement is the process of listening to, collaborating with or informing stakeholders. These stakeholders would be the groups of people who have an investment in the organization, such as participants and athletes, parents, guardians, caregivers, coaches, officials, volunteers and administrators, partners and sponsors (Ferkins & Shilbury, 2013). This engagement could happen in various informal and formal ways. For example, those ways could include but not be limited to, surveys, focus groups, interviews, personal conversations, polls or simple one-question check-ins.

Considerations for doing stakeholder engagement well

- Receive feedback openly, without response

To engage in stakeholder engagement well, it’s essential to truly hear stakeholders’ perspectives. It’s equally important to gain a full understanding about all that the stakeholders have to share. It’s best to listen with open hearts, without judgment, and not respond to what’s offered. It can be difficult to receive constructive or critical feedback. It’s also tempting to correct what seems misunderstood. However, reserving comments and rationale for a later point in the process builds an open environment. In an open environment, all perceptions, both positive and negative, are welcomed. That environment lets stakeholders feel heard, which ultimately builds trust.

- Consider the format carefully

Consider who will conduct the stakeholder engagement and what their relationship is to the topic of engagement or the organization. Some stakeholders perceive direct involvement of an organization as a conflict of interest or an influence of power. Others won’t feel safe sharing their honest opinions without assurance of anonymity. Therefore, it can be wise to seek facilitators who are independent to the topic or organization.

- Develop a plan for reporting back

An important part of doing stakeholder engagement well is to develop a process for reporting back on the feedback received. This can happen in a variety of ways, including circulating a summary report, publishing an article in the organization’s newsletter or on its website, posting videos on social media, holding a town hall, or directly contacting those who participated in the engagement.

An important part of doing stakeholder engagement well is to develop a process for reporting back on the feedback received. This can happen in a variety of ways, including circulating a summary report, publishing an article in the organization’s newsletter or on its website, posting videos on social media, holding a town hall, or directly contacting those who participated in the engagement.

An engagement report should include a summary of what was heard and the resulting decisions that have been made. It should also discuss if stakeholders shared feedback that didn’t lead to changes being made. It may also be an excellent opportunity to correct any misconceptions that were raised during the stakeholder engagement. Be sure to also report on timelines of any resulting actions, especially if they’re longer-term timelines.

Without completing this step, stakeholders may assume the organization never intended to act on the feedback received. Reporting back demonstrates transparency and integrity to the process.

Final thoughts

Stakeholders have rich insights to share based on their backgrounds, lived experiences and positions within sport. Compared to traditional data, stakeholder engagement offers the ability to glean insights that may not have been available otherwise. Engagement offers a way to answer the call to become more collaborative and to co-create the sport experience with those who are invested in it. Incorporating stakeholder engagement into data collection and engagement may be a real-world data source that enhances our ability to deliver a better sport environment for all. That is, a sport environment where everyone feels safe, welcomed and included.

Highlights

- The “who” is as important as the “what” when sport organizations are planning for data, analytics and evidence-based change related to equity, diversity and inclusion.

- When it comes to race and intersectionality, the power of data practices is its ability to help an organization better understand the realities and experiences of those too often neutralized by the majority.

- Sport practitioners, policymakers and funders who don’t embrace intersectional data strategies carry a heightened risk of their decisions and actions perpetuating a status quo they want to change.

“You can’t manage what you don’t measure” is a popular saying in leadership circles. However, knowing what to measure to inform change is a craft altogether.

To advance equity and inclusion in sport, the “who” of measurement is fundamentally as important as the “what.” Indeed, it’s important to understand the perspectives, realities and lived experiences of the people who experience sport as well as those who are pushed away, left on the sidelines, or chose to opt out. And that understanding has never been more important as sport organizations from coast to coast work to reinvent themselves to be safe, inclusive spaces for all.

This article draws on research findings from the Change the Game research project, by the MLSE Foundation with the University of Toronto. The project aims to clarify the value of embracing data practices concerning race and other identity factors for organizations working to achieve greater equity for youth in sport. At the same time, while calling attention to the systemic and many decision-making risks of not doing so.

Sport, society and social justice

MLSE LaunchPad is a youth Sport for Development (SFD) facility in 1 of Canada’s most socioeconomically and culturally diverse neighbourhoods. The facility is located steps from a university that’s undergoing a renaming exercise, because its namesake was an architect of Canada’s Residential Schools system. Just steps away in another direction, a major thoroughfare’s street name is under review for its namesake having worked to delay abolishing slavery.

Social justice movements actively reflect communities’ and individuals’ lived experiences with institutions. A long overdue, social justice reckoning across society has been sparked, within and beyond sport. That spark comes in the cumulative aftermath of: George Floyd’s murder, the discovery of thousands of unmarked graves of residential school children, and the compounding effect of racist incident after incident.

Organizations across Canada have released many statements, hashtags, and commitments to change. These have come from professional sports to national sport organizations and from SFD programs to municipal, physical activity opportunities for youth. Equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) roles and committees are commonplace. “Build Back Better” is a popular mantra on social media with implicit acknowledgement that the status quo is no longer acceptable if sport is really going to live up to the promise and potential of sport as a force for good, and for all.

Changing the game: For whom?

If this is truly a watershed moment, where it’s possible to reinvent sport equitably, then the issue before sport providers is how to operationalize such change. How do we dismantle systems of inequality and centre our sport sector around people it’s intended to serve? And crucially, what data exists to guide where to begin and how best to allocate increasingly limited resources? The unfortunate truth to the question of data sources is there isn’t much available. Although data on sport is routinely analyzed through the lenses of age and gender equity, there’s limited (if any) publicly accessible demographic data to support meaningful insights related to race, geography, household income and other intersecting aspects of marginalization.

These are some of the issues that MLSE Foundation explored when launching its Change the Game research program on access, engagement and equity in youth sport. MLSE Foundation collaborated on this research program with Simon Darnell, Ph.D., and the University of Toronto’s Centre for Sport Policy Studies. Amidst slogans and voices calling for change, the fundamental ethos guiding the Change the Game research team was a clear-eyed commitment to understanding the reality of who we’re aiming to change the game for and what practical and concrete success looks like to them.

Informally referred to behind the scenes as a “youth sport census,” nearly 7000 youth, and parents and guardians of youth, responded from across Ontario as a representatively diverse sample for the research program. The sample spanned race, gender, household income level, ability, geography, immigration status and other demographic variables. It became the largest demographic survey of youth sport access and engagement to date in Canada. The survey explored barriers to participation and ideas for building a better and more equitable sport system for the diversity of Ontario’s youth, in the words of youth. A publicly accessible, open-data portal contains a summary report, interactive results dashboard, and an anonymized data set. Stakeholders who are interested in mining the data, may download the data set for their own learning, planning, funding decisions and policymaking.

The rest of this article isn’t meant to repeat the overall findings. Instead, this article will showcase the value of embracing data practices concerning race and other demographic factors, in pursuit of advancing equity and inclusion goals for youth in sport. By making a case for how race and identity-based data can help drive meaningful action toward a more equitable future, let’s pay homage to the great long-form basketball analysts. To do so, we’ll take a deep dive into 2 specific questions from the original Change the Game study and the insights we can draw.

Understanding blind spots

A series of “I” statements formed a 4‑item, Likert-style questionnaire about youth experiences with racism and discrimination in sport. The questionnaire was aligned with MLSE LaunchPad’s MISSION measurement model for youth data collection. Respondents were asked to select whether they strongly disagreed, disagreed, agreed or strongly agreed with each statement.

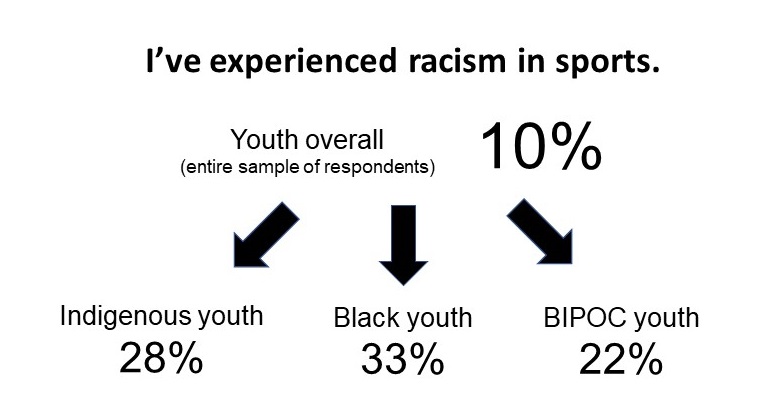

For example, 1 of the statements read: I have experienced racism in sports. Overall, 10% of youth in the study agreed or strongly agreed to having directly experienced racism in sport. Although perhaps meaningful in a dialogue about equity, is 10% on a survey enough for a sport organization, funder or policymaker to meaningfully change course in their decision-making or strategic plan? Hard to say.

Consider now the same statement through the perspective of specific segments of youth in the study.

How does your interpretation of the data change with this additional perspective? If a sport organization is genuinely interested in addressing anti-Black racism or forging right relations with Indigenous communities, does this new story unfolding help to convey a different level of urgency for action?

This is the power of demographic data: enabling one to look in-depth to better understand vital stories and perspectives that are otherwise at risk of being neutralized by the majority.

Now let’s consider a different example.

The fallacy of averages

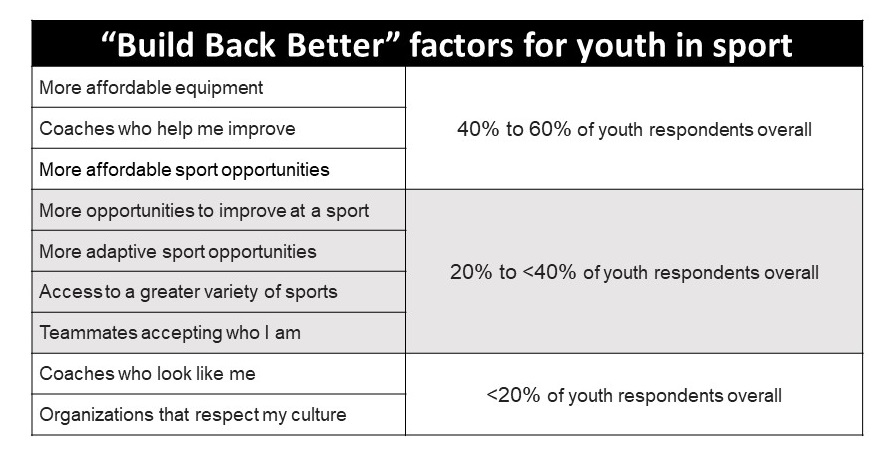

Against the backdrop of “Build Back Better” becoming an increasingly popular slogan or hashtag, youth were asked to shed light in practical terms on what that might look like in their reality. A total of 9 thematic areas (or factors) received greater than 10% of support among youth overall, as follows:

To be clear, each of these 9 factors is an important and sound investment area to improve accessibility and experiences in sport, including the 3 factors that polled the highest.

However, equity isn’t a first-past-the-post concept. In many respects, the opposite is true. To get real about advancing racial equity for youth in sport in an authentic way, one must align their data practices accordingly. Doing so can help by enabling a deeper awareness of the issues and perspectives of constituencies whose relative size may not be large enough to move the overall averages.

With that in mind, let’s explore 2 of the factors in more detail. “Coaches who look like me” and “Organizations that respect my culture” were each called out as important by less than 20% of youth in the overall sample. Do any interesting insights emerge when race-based and Indigenous-identity data lenses or filters are applied?

With that in mind, let’s explore 2 of the factors in more detail. “Coaches who look like me” and “Organizations that respect my culture” were each called out as important by less than 20% of youth in the overall sample. Do any interesting insights emerge when race-based and Indigenous-identity data lenses or filters are applied?

As it turns out, yes.

Having “coaches who look like me” was identified by approximately 10% of youth overall, the lowest among the 9 factors. However, a closer look affirms this item as having outsized importance to specific demographics within the sample, notably South Asian youth (more than 20%) and Black youth (more than 30%). When reflecting on this 9‑factor list of Build Back Better, how do these additional details inform your own decision-making or perspective on the most critical issues to prioritize addressing?

Exploring who selected “Organizations that respect my culture” through a race-based and Indigenous-identity lens is also interesting, for a different reason.

The distribution pattern is obvious, especially when compared to the Build Back Better table in Figure 3. More than 1 in 5 youth from all 8 of the unique BIPOC categories in this survey called for respect for their culture, even though that rated proportionally much lower in the overall sample of youth.

Decision-making risks

Neither of these examples discredits the importance of any of the other Build Back Better factors cited above. They’re all vital components of a healthy future for youth sport and need attention from providers, policymakers and funders. These examples are provided to reinforce the value of intentionally including demographics in an organization’s data collection plans. Those demographics can shed light more meaningfully on how different experiences and ideas can show up for different segments of the population. If instead of race, the variable of interest had been gender, household income, ability or other intersectional factors of identity, then the results displayed may have told a different story. The core purpose or value proposition is for an organization’s EDI strategy and decision-making process to be informed by the people they intend to serve.

Applying demographic data collection in your organization

Before you can improve an organization’s measurement and evaluation plans, you require some baseline competencies in data management, including privacy, ethics and analysis. Those competencies can help you apply some of the methods and tactics to integrate intersectional demographic lenses to your organization’s plans. Here are tips an organization can consider when getting started. They’re grounded in 4 pillars of transparency, trust, trying it out and talking it out.

- Transparency

If you’re collecting demographic information from staff, coaches, athletes, families or other stakeholders essential to your organization’s success, it’s key to be open and honest with them. For example, openly share why you’re collecting identity-based information, how you’ll handle the information, who will see it, and what you’ll do with the insights you learn. Engaging your core constituencies in these ways can help demonstrate respect, enable meaningful and informed consent to share data, and encourage active partnership on a shared journey to shape a more equitable future.

- Trust

Trust often makes all the difference between complete and incomplete information on a survey or profile page. Whether a respondent has a trusting relationship with the sport organization or its staff will often determine whether that respondent fills out all the fields on their registration or profile forms. Without that trust, they may only complete the required fields. It’s the difference between responding fulsomely to a multiple-choice question on a survey versus just selecting the “prefer not to answer” option. Individual respondents (data contributors) must believe the organization has their back and will use their data to make meaningful improvements. Sometimes this can take time, and it’s OK to be patient.

For example, at the MLSE LaunchPad SFD facility, this is a pattern seen when new members sign up for the first time. Youth, parents and guardians often fill out the minimum required information to get started on attending programs. Then, what and how much they’re willing to share changes over time. Their feedback and sharing practices grow after having built a trusting relationship with staff and the organization. When new members have gained an understanding of how data contributes to understanding and improvements, then that also contributes to enhanced sharing.

- Try (it out)

To echo Courtney Szto, Ph.D., of Queen’s University at the 2021 Anti Racism in Hockey Incubator: Do something! Too many ideas for change get left on the sidelines. Trying to do right typically trumps inaction, even if a concept is imprecise or not fully formed. Even if it’s a small step forward, take a shot. If you don’t achieve your intended outcome, learn from it, regroup, change your approach and try again. Progress can take unusual paths, but there’s tremendous value in letting stakeholders see that you’re actively trying to make a difference.

- Talk (it out)

Data practices don’t come naturally to everyone. If you’re considering a new idea, direction or practice, we encourage you to reach out to someone in the field to help critically assess your approach. If you’re a sport or SFD organization interested in having a sounding board on what an intersectional approach to demographic data collection could look like in your setting, then reach out to a member of the MLSE LaunchPad Research and Evaluation Team.

In closing, sport providers, funders and policymakers want to prioritize meaningful action toward equity, their toolkit to shape the future of sport should include embracing intersectional data collection practices, including race and other equity-related demographic factors. However, keep in mind that there’s potential risk if sport leaders are relying on data featuring top line averages and rankings without an intersectional approach. The data informing their decisions carries a heightened risk of being influenced by the majority and increases the likelihood of actions that perpetuate the very systems they’re supposedly seeking to reshape.

Recommended resources

Centre for Sport Policy Studies, University of Toronto

Indigeniety, Diaspora, Equity and Anti-racism in Sport (IDEAS) Research Lab

About MLSE LaunchPad

MLSE LaunchPad is a 42000 square foot Sport For Development facility in downtown Toronto built and supported by the MLSE Foundation to advance positive developmental outcomes for youth, aged 6 to 29, who face barriers.

This blog post recaps the second webinar in the 4‑part Engaging Girls and Women in Sport mini-series. SIRC and Canadian Women & Sport co-hosted the mini-series, which you can access and learn more about by visiting our SIRC Expert Webinars page.

—

With the rise of big data and analytics, organizations across all industries are looking to use data when making decisions. There are many reasons why sport organizations may want to collect and use data. For example, data can help plan quality sport programs with gender equity at the centre. In this blog, we highlight the key takeaways from our discussion with academics and sport leaders on the importance of data collection to design and improve programs.

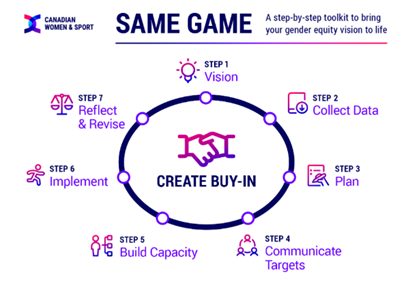

For many people, the idea of working with data can be intimidating. Canadian Women & Sport created Same Game as one way to make people more comfortable with data. Same Game is a free, online, step-by-step toolkit to help sport leaders use data to turn gender equity ideas into reality.

Introducing the toolkit, webinar panelist Shannon Kerwin, a Brock University researcher with the E-Alliance Gender and Equity in Sport Research Hub, explained that it breaks down the process into 7 steps. The toolkit begins with a vision to help organizations understand their “why,” then moves on to data collection, planning, communicating targets, building capacity, implementation, and, finally, reflection and revision to make lasting and impactful change.

The other 2 panelists, Paula McKenzie and Crystal Watson, shared their experiences with using the Same Game toolkit. McKenzie, the executive director of one of the largest track and field clubs in Canada, Caltaf athletic association, explained the framework of 4D’s: Discovery, Data collection, Detailed planning or implementation, and “Down-the-road” thinking.

Then Watson, a volunteer board member with the Alberta Sport Development Centre, shared her experiences of collecting data through a province-wide study with over 400 high-school participants. Both Watson and McKenzie emphasized that the toolkit was user-friendly and designed to help organizations navigate the complex world of data.

Why is data collection important?

Data helps you look at a situation objectively. It tells a story based on facts and provides organizations with numbers that they can use to make decisions. Instead of relying on what you “think” is happening, using data allows you to make decisions based on what you “know” is really happening.

“When we’re looking at data, it helps inform our decisions. Data shows you the picture of what you’re looking at. As human beings we have our own biases. If I come into my own research projects, I’m thinking something might happen, but when I collect my data, I look and think perhaps there’s something different going on.”

Shannon Kerwin

- Data helps with efficiency and resource allocation

Lacking enough time or resources can be common barriers for sport organizations. But, using data can help organizations focus on the right thing. And, as a result, data helps them use their time and resources more efficiently and make better decisions.

“…data increases the effectiveness of targeting the right initiative, program or strategy, so that’s key. We know all clubs are working in a space where you don’t have infinite resources so where you allocate the resources becomes so much more important.”

Shannon Kerwin

- Data creates stakeholder buy-in

Finally, data has the power to elicit support from stakeholders, including board members, coaches and athletes. Data can be helpful when making immediate changes within an organization. Data can be useful externally too, when applying for grants.

“It helps to create buy-in. Buy-in from parents [or guardians], athletes, coaches, athletic directors, different people in your organization, the board to ensure they’re understanding what you’re doing and why you’re doing it. And even to redirect you if you need to zig and zag which often happens.”

Crystal Watson

Collecting and using data

Challenges can arise during the data collection stage. If you’re getting few responses, take a step back and try to understand your target demographic. Then, find the channels that will get their attention, incentivize participants and find ways to keep them engaged.

Challenges can arise during the data collection stage. If you’re getting few responses, take a step back and try to understand your target demographic. Then, find the channels that will get their attention, incentivize participants and find ways to keep them engaged.

“We used our social media channels. At the beginning, I was sending emails and it finally dawned on me that if I’m younger than I am, I’m probably not reading all the emails, but if I put something out on Instagram, I’m probably reading that.”

Paula McKenzie

Another approach is to identify influential individuals and turn them into champions to promote participation and change:

“The big thing that worked for us, the reason we could collect so many responses [was] because we had a personal connection within the school. We had a couple of teachers who were going to champion our survey tool and get it approved.”

Crystal Watson

Finally, the sports community can be a great resource. As Kerwin pointed out, community connections within clubs are strong. Reaching out to others can result in support or a referral that will guide you in the right direction.

After collecting data, it’s common for organizations to not know what to do next. The first step in understanding your data, according to Kerwin, is to form a summary. This helps identify trends, challenge or support existing assumptions, and understand what other pieces of data you need to explore or collect. Beginning with a summary lays out the foundation for your next steps.

Using data for gender equity

At the end of the webinar, the panelists shared their ideas for using data to realize organizations’ gender-equity goals.

At the end of the webinar, the panelists shared their ideas for using data to realize organizations’ gender-equity goals.

The first step is to understand your organization’s “why.” This can help you understand what you want to achieve as an organization, says Kerwin. As the Same Game toolkit shows, having such a vision for your organization builds the foundation for the next steps, including collecting, analyzing and using data.

Being open-minded is another important element of working with data. Watson emphasized the importance of keeping an open mind and not letting pre-determined expectations or assumptions influence your conclusions.

Finally, McKenzie explained that data doesn’t have to be scary. Although there’s often a steep learning curve to working with data, there are also many resources available. These include academic researchers and peers within the sports community. Working together to share best practices can make working with data fun rather than scary.

Sport organizations are beginning to realize that data is powerful and can have many benefits. Importantly, resources such as the Same Game toolkit can help organizations to start on their data collection and analysis journey. With time, practice, and by leaning on others for support, organizations can start using data to realize a common vision of gender equity.

About the panelists

To learn more about the Engaging Girls and Women in Sport Mini-Series and the webinar panelists, check out the SIRC Expert Webinars page.

About Canadian Women & Sport

Canadian Women & Sport is dedicated to creating an equitable and inclusive Canadian sport and physical activity system that empowers girls and women—as active participants and leaders—within and through sport. With a focus on systemic change, we partner with sport organizations, governments, and leaders to challenge the status quo and build better sport through gender equity.

Most concussions in youth volleyball are the result of ball-to-head contacts during practice or warm-ups. To improve athlete safety on the court, Volleyball Canada introduced a new rule in 2018 to prevent athletes from going under the net to retrieve the ball during warm-up drills, a high-risk situation for ball-to-head contact.

Highlights

- Along with current educational and technological initiatives, sport organizations have the opportunity to introduce specific strategies to protect against the risks of concussion within their respective sports.

- To develop effective prevention strategies, it’s necessary to understand the extent of the concussion problem and research the factors and mechanisms that contribute to concussion risk.

- Interventions, such as rule changes for reducing concussion risks, should be both targeted and sport-specific. Since resources are often limited, sport organizations should focus on evidence-based approaches to develop and implement interventions.

- Even after introducing an intervention, continually gathering epidemiological data and re-evaluating concussion risks is vital for assessing the effectiveness of a sport organization’s concussion prevention strategy.

“You have a concussion.” These are words that no athlete wants to hear. What exactly does it mean? Perhaps a full stop to sport-related activities. Or, no longer being able to practise, train or compete. Maybe uncertainty around recovery times or a return to play, and questions about future risks and implications.

In recent years, the conversation around concussion and its short-term and long-term effects has become a larger part of the sport injury prevention landscape (Davis et al., 2020; McCrory et al., 2017). In a departure from historical associations, the dialogue about brain injuries is no longer limited to high-risk, impact sports. Sport-related concussion and brain trauma is now in the forefront of the modern sporting world, with high-profile cases in professional leagues, players’ class-action litigations, and emerging concerns about potential risks for neurodegenerative disease (for example, chronic traumatic encephalopathy).

In recent years, the conversation around concussion and its short-term and long-term effects has become a larger part of the sport injury prevention landscape (Davis et al., 2020; McCrory et al., 2017). In a departure from historical associations, the dialogue about brain injuries is no longer limited to high-risk, impact sports. Sport-related concussion and brain trauma is now in the forefront of the modern sporting world, with high-profile cases in professional leagues, players’ class-action litigations, and emerging concerns about potential risks for neurodegenerative disease (for example, chronic traumatic encephalopathy).

For many sport organizations, this heightened focus on concussion has meant increasing efforts to develop and implement preventative strategies, which can help protect participants from suffering concussions in their sport. Athletic careers can be paused or permanently ended because of concussion injuries and related consequences (Bergeron et al., 2015; Sedney et al., 2011). Therefore, it’s important to improve all sport stakeholders’ knowledge about concussion signs, symptoms and management strategies. That applies to participants, families, coaches, trainers and other sport personnel (Tator, 2012).

But beyond educating stakeholders, what other steps can sport organizations take to reduce the risk of concussion across all levels of sport and recreation? Similar to other types of sport injuries, it’s important to first understand the burden of injury that athletes face, and focus on evidence-informed injury prevention strategies. Such strategies combine the best research practice with real-world practice and expertise (Pike et al., 2015).

How should sport organizations continue to address this issue and focus their efforts on developing interventions for concussion injury prevention in their respective sports? Ineffective strategies often continue to be practised at great expense to existing resources (Pike et al., 2015), without successfully protecting athletes from concussion risks. With limited resources available, it’s critical that sport organizations invest in strategies that are most likely to effectively reduce the risk for injuries. Taking an evidence-informed approach to injury prevention is vital to planning and implementing interventions targeted at reducing concussion in sport.

How should sport organizations continue to address this issue and focus their efforts on developing interventions for concussion injury prevention in their respective sports? Ineffective strategies often continue to be practised at great expense to existing resources (Pike et al., 2015), without successfully protecting athletes from concussion risks. With limited resources available, it’s critical that sport organizations invest in strategies that are most likely to effectively reduce the risk for injuries. Taking an evidence-informed approach to injury prevention is vital to planning and implementing interventions targeted at reducing concussion in sport.

In this article, we describe the processes that have informed Volleyball Canada’s approach to concussion prevention research, how we’ve used data to inform our concussion prevention strategy, and what we’ve learned along the way.

The E’s of sport injury prevention

Parachute, a Canadian national charity dedicated to injury prevention, highlights “The Three E’s of Injury Prevention” in The Canadian Injury Prevention Resource. The E’s (education, enforcement and engineering) were first developed for industrial safety. They’re frameworks that can help guide the development of community-based, injury prevention programs and initiatives.

- Education involves reducing injury risk by providing stakeholders with educational information or training, or both. For example, the Coaching Association of Canada offers coaches the “Making Head Way” Concussion eLearning module. Developed as part of the National Coaching Certificate Program (NCCP), “Making Head Way” is for assisting coaches in identifying and managing sport-related concussion. Many sport organizations, including Volleyball Canada, have mandated that coaches must complete Making Head Way as part of their coach certification pathways and professional development.

- Enforcement involves implementing preventative rules, policies, and regulations to reduce the risk of injury. For instance, in Ontario, Rowan’s Law legislation mandates that sport organizations establish Removal-from and Return-to-sport protocols. As well, all participants must review the Concussion Awareness Resources and Concussion Code of Conducts every 12 months. The Ontario Volleyball Association has an excellent example of a concussion policy and protocol that meets this legislation. Another example of a major policy change at the National Sport Organization (NSO)-level was Hockey Canada’s removal of body-checking from Pee Wee-level hockey in 2013. While that decision was somewhat controversial at the time, it has since been shown to effectively reduce the incidence of concussions among young hockey players across Canada (Emery et al., 2017).

- Engineering means developing products and technologies that will reduce the risk of injury. This can include advances in protective equipment, such as helmets, to better protect against brain injury in sport. The adoption of helmets has been effective in reducing catastrophic or traumatic brain injuries (such as skull fractures and brain bleeds). However, the helmet designs currently being used are limited in their ability to protect against concussion (Hoshizaki et al., 2014; McCrory et al., 2017; Tator, 2012).

Other injury prevention and public health researchers have expanded upon these key concepts with 2 additional E’s to consider (epidemiology and evaluation) when taking evidence-informed strategies to injury prevention interventions (Pike et al., 2015; Tator, 2012).

- Epidemiology involves conducting research to gain precise knowledge of how injuries like concussion happen within a given sport. While some characteristics like age, biological sex or previous concussion history have been shown to affect risk and recovery times, understanding these “non-modifiable risk factors” is still important for guiding interventions and strategies (Tsushima et al., 2019).

- Evaluation involves monitoring, assessing and reviewing injury prevention programs and strategies to ensure their effectiveness, make adjustments, and show impact. This critical step includes collecting information that can improve and sustain the use of the intervention.

A “sequence of prevention” model for injury research

In 1992, Van Mechelen et al. described a “sequence of prevention” model for injury research, which others have built and expanded upon to guide modern public health initiatives for injury prevention (Pike et al., 2015). Grounded in this sequence of prevention model, the Canadian Injury Prevention Resource outlines 5 functional elements to successfully help prevent injuries:

In 1992, Van Mechelen et al. described a “sequence of prevention” model for injury research, which others have built and expanded upon to guide modern public health initiatives for injury prevention (Pike et al., 2015). Grounded in this sequence of prevention model, the Canadian Injury Prevention Resource outlines 5 functional elements to successfully help prevent injuries:

- Step 1: “Surveillance,” to identify and describe the extent of the sport injury problem.

- Step 2: “Risk and protective factors,” to identify the causes and mechanisms contributing to the risk of injury.

- Step 3: “Selecting and designing an intervention,” to develop measures that are likely to reduce the risk or severity of the sport injury.

- Step 4: “Program and policy implementation,” to apply evidence-based prevention strategies to reduce the risk of injury.

- Step 5: “Evaluation and monitoring,” to plan tangible ways in which to analyze and determine the effectiveness of the intervention.

Step 5 is often overlooked. However, it’s extremely important in figuring out whether an intervention has been successful in reducing injury risk. This frequently means revisiting Step 1 to re-identify the extent of the injury (Tator, 2012, Van Mechelen, 1992). This evaluation process is, ideally, an ongoing component of the initial Step 1 process rather than a separate step altogether.

It’s also important to note that these 5 steps don’t have to be completed in order. Since sport organizations often have limited resources, they may need to adapt to real-world circumstances to make efficient use of their time and efforts. To do so, sport organizations should focus on developing strategies and interventions that are both targeted and sport–specific for reducing the risk of concussion (Pike et al., 2015; Tator, 2012).

Concussion prevention research with Volleyball Canada

Although concussions happen in volleyball, there’s been little evidence-based research informing prevention strategies in this sport. Using the sequence of prevention model, Volleyball Canada set out to understand injury rates (Step 1) and identify specific risk factors and injury mechanisms (Step 2) for concussion among its youth club athletes (aged 14 to 19).

Club athletes compete provincially and nationally, with the season beginning in the fall, and ending each May with Volleyball Canada’s National Championships. With the help of researchers from the Sport Injury Prevention Research Centre (SIPRC) at the University of Calgary, a survey on Canadian youth volleyball athletes, from 2016 to 2018, helped identify rates of concussion, risk factors and injury mechanisms (Meeuwisse et al., 2017). Additionally, the 2018 Volleyball Canada National Championships brought together 9500 athletes and 2000 coaches from all age classes, to one location, presenting us with a unique opportunity to gather extensive epidemiological data on concussion injuries and risk factors.

The SIPRC study’s results showed that most concussions in youth volleyball were caused because of ball-to-head contacts (57%) and the majority (62%) of these occurred during practice or warm-ups. This meant that a large proportion of concussions were from non-competitive, controlled environments, which could be specifically targeted for intervention (Meeuwisse et al., 2017). Using this information, Volleyball Canada developed measures (Step 3) to minimize the risk of ball-to-head contact during these controllable environments (specifically, pre-game warm-up routines).

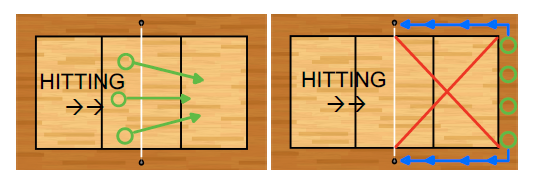

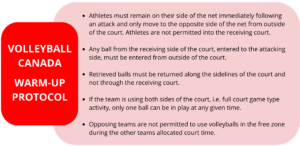

For example, during the standard hitting warm-up routine, a player would attack a ball over the net and immediately run under the net to retrieve the ball. This created a high-risk situation since it was more than likely that this athlete would be struck in the head by the next ball being hit by a teammate. To reduce the incidence of concussions during warm-up, Volleyball Canada introduced a new rule in 2018, which disallowed athletes from running under the net and over to the opposite side of the court to retrieve their ball during the standard hitting warm-up routine (Step 4).

Most provincial sport organizations adopted this new “Warm-up Protocol” rule for their 2019 competitive club season. Volleyball Canada enforced it at its national championships.

Most provincial sport organizations adopted this new “Warm-up Protocol” rule for their 2019 competitive club season. Volleyball Canada enforced it at its national championships.

To tackle Step 5, Volleyball Canada has been actively conducting new studies to evaluate how effective this hitting warm-up rule change has been on reducing concussion rates. The COVID-19 pandemic and lack of competition since 2019 has delayed data collection and analyses. However, initial results suggest that the odds of reporting a concussion during the pre-game hitting warm-up routine remain unchanged since implementing the 2018 rule change.

In re-evaluating the risk of concussion sustained during warm-ups, interestingly, youth volleyball athletes have reported more concussions occurring during the unstructured portion of the pre-game team warm-up. This usually involves players using a ball to rally one-on-one with a partner, or more commonly known in volleyball as “pepper.” This highlights the importance of collecting data and re-evaluating the effectiveness of injury prevention interventions, as new information can continue to fill the knowledge gaps in concussion injury risks and inform future strategies.

Lessons learned and next steps

Though the process is ongoing, Volleyball Canada remains committed to using data and evidence-informed approaches to develop strategies for reducing concussion risks. However, this process is often difficult and resource-intensive for sport organizations. For example, competing priorities, possible resistance to change or new methods, or simply a lack of time, capacity or expertise, are all challenges that face sport organizations when investing in an evidence-informed approach to injury prevention (Pike et al., 2015).

Though the process is ongoing, Volleyball Canada remains committed to using data and evidence-informed approaches to develop strategies for reducing concussion risks. However, this process is often difficult and resource-intensive for sport organizations. For example, competing priorities, possible resistance to change or new methods, or simply a lack of time, capacity or expertise, are all challenges that face sport organizations when investing in an evidence-informed approach to injury prevention (Pike et al., 2015).

What were some of the important lessons Volleyball Canada learned from its concussion prevention strategies to date?

1. Get creative and innovate

The gathering of quality epidemiological data is both time-consuming and difficult, especially at a national level. As this describes Step 1 of the 5-step process, investing in the resources to help understand the entire scope of the problem, can be a daunting first step.

Consistent data collection allows for assessment of historical trends, or retrospective analysis of the effects that other equipment, rule or policy changes may have on concussion rates (whether the changes are intentional or not)!

Therefore, it’s ideal to collect this type of epidemiological data as part of the membership or event registration process. Starting in fall 2021, Volleyball Canada’s new virtual registration systemwill give the organization another way to potentially help facilitate future information-gathering processes.

2. Build partnerships

With limited resources for research initiatives, partnering with external research or community groups can increase a sport organization’s capacity to conduct concussion injury prevention work. Developing initiatives with these partners, such as universities and hospitals, can help sport organizations gain access to trained staff capable of taking on some of the research burden.

With limited resources for research initiatives, partnering with external research or community groups can increase a sport organization’s capacity to conduct concussion injury prevention work. Developing initiatives with these partners, such as universities and hospitals, can help sport organizations gain access to trained staff capable of taking on some of the research burden.

These external groups may even have similar mandates as the sport organization’s injury prevention goals. For example, the University of Calgary SIPRC focuses on working with community partners to reduce the risk of injury in sport and recreation, with a particular emphasis on preventing youth injuries.

3. Engage in ongoing evaluation

By gaining sport-specific knowledge about how concussions occur and where the highest risks exist will guide and direct the development of specific interventions and strategies. Learning that concussions primarily occurred from ball-to-head contact within controlled environments helped Volleyball Canada adopt rule changes to reduce the risk of exposure to that mechanism.

However, equally important is the ongoing re-evaluation process, which continues to provide data on the effectiveness of this rule change. Interventions may or may not work, or may take some time to deliver tangible results. Without this re-evaluation process, sport organizations can’t know whether an intervention has been effective or successful in reducing the risks for concussion injury.

It’s important to consider incorporating this re-evaluation process right from the start of Step 1. That way the continual evidence-based approach can be supported by the initial efforts and infrastructure of setting up data collection and information-gathering measures.

Conclusion

“Although we have come a long way in understanding concussions in volleyball, there is still much more to do. We are still working diligently on the establishment of an effective and efficient surveillance system. Once we get to that in place, developing and assessing interventions strategies will be the easy part.”

Kerry Macdonald, Director of Sport Science, Medicine and Innovation at Volleyball Canada

Understanding the extent of the problem and identifying the factors that create concussion injury risk is key to implementing effective prevention strategies. For sport organizations, these strategies should be targeted and sport-specific, because every sport may have unique injury mechanisms that contribute to concussion risk. Alongside existing educational and technological strategies, an evidence-informed approach is the most effective way of developing further preventative measures that protect athletes and reduce the burden of concussion injury.

Over a coffee, we recently reminisced about different sporting environments we’ve worked in and how many times we’ve seen expensive technological solutions sit in a corner, collecting dust. Perhaps you can relate to the pattern. A new technology hits the market, and a few marquee teams or athletes adopt it. You truly believe that the technology will help you in the same way that it’s helping them. You purchase the technology and anticipate how great it’s going to be. Then, for whatever reason, it doesn’t go as you anticipated. Using the technology is cumbersome. Athletes or staff resist the technology. You don’t know what the data means or what you should do differently now that you have the data. Eventually, the value isn’t as apparent as you first anticipated, and you eventually stop using the technology. The dust collection begins.

These days, coaches are inundated with technological options claiming to offer “solutions” for athletes and teams. However, many coaches have limited budgets and don’t want technological investments to fail. Based on experiences implementing technology in different applied sport settings, we’ve proposed using a critical decision-making framework before implementing technology in sport (Windt et al., 2020).

In this blog, we review 4 key questions for coaches and other decision-makers to ask if they want new technology to help, not hinder, their ability to coach effectively.

Question 1: Is the data useful?

Everyday, it seems a new technology hits the market with bold claims and fancy marketing. Many technologies are intriguing, and as a coach, it’s easy to be curious or interested. However, the first thing to consider isn’t whether the technology is exciting, but whether it’ll deliver on its promises to inform decisions.

Practically, coaches should “start with the end in mind” (Covey, 2004) by envisioning their decision-making process, and how the technology could contribute. The technology’s data should inform coaches’ decision-making, not “make” the decision for the coach (Gamble et al., 2020).

Practically, coaches should “start with the end in mind” (Covey, 2004) by envisioning their decision-making process, and how the technology could contribute. The technology’s data should inform coaches’ decision-making, not “make” the decision for the coach (Gamble et al., 2020).

Another important consideration is whether coaches could access the same information in another, but more affordable way, especially when budgets are tight. For example, global positioning systems (GPS) can provide information about players’ training volumes and physical capabilities, such as maximum velocity, and the information can be aggregated to understand a team’s training progression throughout a micro or macro cycle. If the latter (team load progression) is the coach’s priority, consistently collecting the session rating of perceived exertion (sRPE) responses from each athlete could provide insight into how the team’s training sessions vary across the training cycle. This would reduce the need for GPS to answer this specific question. If players’ maximum velocities during match play are the most important question, then GPS will prevail as the answer.

If coaches can’t imagine how the information would make life easier with more effective decision-making, or if they can already access similar information through other means, then there’s no need to further consider the technology.

Question 2: Is the data trustworthy?

Technology companies have a bottom line: their own. Often, they ultimately care more about selling their product to increase profits than about openly sharing their products’ imperfections. Given that commercial products vary in accuracy, and none capture information perfectly (Linke et al., 2018; Stone et al., 2020), coaches must consider if marketing promises are to be “sufficiently believed.”

This question has 2 parts. First, can the technology be believed? In the scientific realm, this is about validity and reliability. Broadly, validity assesses if the technology is measuring what it promises to measure, while reliability speaks to its consistency and degree of error when providing measurements (Impellizzeri & Marcora, 2009). To answer this believability question, coaches can search for academic, peer-reviewed papers about the technology such as the 2 papers referenced in the previous paragraph. Coaches can also speak to someone in a related academic field to recap available literature on the company. No news or no papers is often not a good sign.

This question has 2 parts. First, can the technology be believed? In the scientific realm, this is about validity and reliability. Broadly, validity assesses if the technology is measuring what it promises to measure, while reliability speaks to its consistency and degree of error when providing measurements (Impellizzeri & Marcora, 2009). To answer this believability question, coaches can search for academic, peer-reviewed papers about the technology such as the 2 papers referenced in the previous paragraph. Coaches can also speak to someone in a related academic field to recap available literature on the company. No news or no papers is often not a good sign.

The second question is about sufficiency, after the validity and reliability have been evaluated. Since no measure is perfectly valid or reliable, one must judge whether the errors are small enough that the data can still be sufficiently used for the coaches’ particular purpose. For example, while errors are always present, if a GPS unit is off by an average of 10 metres each day, you’ll be more comfortable relying on it for reviewing a training session’s physical demands than if it’s off by 1000 metres per day. Ultimately, trusting technology is a judgement call, based on understanding a technology’s limitations and weighing them against how precise the data must be to inform your decision.

Question 3: Can coaches access and use the data effectively?

While a main goal of technology is to provide data to help with decision-making, actually getting the necessary data may be simple or unreasonably cumbersome. When evaluating whether a technology is appropriate for your needs, ask for a trial. Trials can help coaches discover if they can access the necessary information and evaluate whether the technology meets their needs. For example, how long does it take to get the data? Is it available live or post-session? Can data be accessed on a cell phone or only on a computer? Is there enough detail? Can data be customized, and how is it displayed? Can the data be exported to compare it to other available information? The importance of each question depends specifically on each coach’s context. Trialing a technological solution can help coaches to answer each of these questions (Torres-Ronda & Schelling, 2017).

While a main goal of technology is to provide data to help with decision-making, actually getting the necessary data may be simple or unreasonably cumbersome. When evaluating whether a technology is appropriate for your needs, ask for a trial. Trials can help coaches discover if they can access the necessary information and evaluate whether the technology meets their needs. For example, how long does it take to get the data? Is it available live or post-session? Can data be accessed on a cell phone or only on a computer? Is there enough detail? Can data be customized, and how is it displayed? Can the data be exported to compare it to other available information? The importance of each question depends specifically on each coach’s context. Trialing a technological solution can help coaches to answer each of these questions (Torres-Ronda & Schelling, 2017).

Question 4: Is the technology usable in real-life situations?

When implemented, what burden will the technology impose on coaches, athletes, and support staff? This may be among the most overlooked questions when considering technological options for sport. Using technology costs 1 or more people their time, energy or convenience. For example, implementing GPS with a soccer team could easily take up to 4 hours a day: 1 hour to prepare the equipment, 2 hours to monitor the session and assign players to the proper drills, and 1 hour to process data, create reports, and provide interpretation. When deciding if a technology is worth it, don’t just weigh the price, but also factor in the cost it’ll demand of everyone involved.

Conclusion

It’s easy to think that new technology will solve the problems we’re having in sport. Coaches and practitioners (especially in amateur sport or in sporting organizations with fewer resources and smaller budgets) may believe that technologies already used in professional environments are the solution. In fact, while professional sport environments often have lucrative budgets and excess technologies at their disposal, technologies can distract from the real performance process and collect dust when implementation fails. Many teams succeed with low budgets and few technologies. In turn, many incredibly well-funded teams fail, even with many technological toys. We hope that by encouraging practitioners to ask these 4 questions, we’ll help others avoid this trap, ensuring that technology they adopt is a help, not a hindrance.