Highlights

- Along with current educational and technological initiatives, sport organizations have the opportunity to introduce specific strategies to protect against the risks of concussion within their respective sports.

- To develop effective prevention strategies, it’s necessary to understand the extent of the concussion problem and research the factors and mechanisms that contribute to concussion risk.

- Interventions, such as rule changes for reducing concussion risks, should be both targeted and sport-specific. Since resources are often limited, sport organizations should focus on evidence-based approaches to develop and implement interventions.

- Even after introducing an intervention, continually gathering epidemiological data and re-evaluating concussion risks is vital for assessing the effectiveness of a sport organization’s concussion prevention strategy.

“You have a concussion.” These are words that no athlete wants to hear. What exactly does it mean? Perhaps a full stop to sport-related activities. Or, no longer being able to practise, train or compete. Maybe uncertainty around recovery times or a return to play, and questions about future risks and implications.

In recent years, the conversation around concussion and its short-term and long-term effects has become a larger part of the sport injury prevention landscape (Davis et al., 2020; McCrory et al., 2017). In a departure from historical associations, the dialogue about brain injuries is no longer limited to high-risk, impact sports. Sport-related concussion and brain trauma is now in the forefront of the modern sporting world, with high-profile cases in professional leagues, players’ class-action litigations, and emerging concerns about potential risks for neurodegenerative disease (for example, chronic traumatic encephalopathy).

For many sport organizations, this heightened focus on concussion has meant increasing efforts to develop and implement preventative strategies, which can help protect participants from suffering concussions in their sport. Athletic careers can be paused or permanently ended because of concussion injuries and related consequences (Bergeron et al., 2015; Sedney et al., 2011). Therefore, it’s important to improve all sport stakeholders’ knowledge about concussion signs, symptoms and management strategies. That applies to participants, families, coaches, trainers and other sport personnel (Tator, 2012).

But beyond educating stakeholders, what other steps can sport organizations take to reduce the risk of concussion across all levels of sport and recreation? Similar to other types of sport injuries, it’s important to first understand the burden of injury that athletes face, and focus on evidence-informed injury prevention strategies. Such strategies combine the best research practice with real-world practice and expertise (Pike et al., 2015).

How should sport organizations continue to address this issue and focus their efforts on developing interventions for concussion injury prevention in their respective sports? Ineffective strategies often continue to be practised at great expense to existing resources (Pike et al., 2015), without successfully protecting athletes from concussion risks. With limited resources available, it’s critical that sport organizations invest in strategies that are most likely to effectively reduce the risk for injuries. Taking an evidence-informed approach to injury prevention is vital to planning and implementing interventions targeted at reducing concussion in sport.

In this article, we describe the processes that have informed Volleyball Canada’s approach to concussion prevention research, how we’ve used data to inform our concussion prevention strategy, and what we’ve learned along the way.

The E’s of sport injury prevention

Parachute, a Canadian national charity dedicated to injury prevention, highlights “The Three E’s of Injury Prevention” in The Canadian Injury Prevention Resource. The E’s (education, enforcement and engineering) were first developed for industrial safety. They’re frameworks that can help guide the development of community-based, injury prevention programs and initiatives.

- Education involves reducing injury risk by providing stakeholders with educational information or training, or both. For example, the Coaching Association of Canada offers coaches the “Making Head Way” Concussion eLearning module. Developed as part of the National Coaching Certificate Program (NCCP), “Making Head Way” is for assisting coaches in identifying and managing sport-related concussion. Many sport organizations, including Volleyball Canada, have mandated that coaches must complete Making Head Way as part of their coach certification pathways and professional development.

- Enforcement involves implementing preventative rules, policies, and regulations to reduce the risk of injury. For instance, in Ontario, Rowan’s Law legislation mandates that sport organizations establish Removal-from and Return-to-sport protocols. As well, all participants must review the Concussion Awareness Resources and Concussion Code of Conducts every 12 months. The Ontario Volleyball Association has an excellent example of a concussion policy and protocol that meets this legislation. Another example of a major policy change at the National Sport Organization (NSO)-level was Hockey Canada’s removal of body-checking from Pee Wee-level hockey in 2013. While that decision was somewhat controversial at the time, it has since been shown to effectively reduce the incidence of concussions among young hockey players across Canada (Emery et al., 2017).

- Engineering means developing products and technologies that will reduce the risk of injury. This can include advances in protective equipment, such as helmets, to better protect against brain injury in sport. The adoption of helmets has been effective in reducing catastrophic or traumatic brain injuries (such as skull fractures and brain bleeds). However, the helmet designs currently being used are limited in their ability to protect against concussion (Hoshizaki et al., 2014; McCrory et al., 2017; Tator, 2012).

Other injury prevention and public health researchers have expanded upon these key concepts with 2 additional E’s to consider (epidemiology and evaluation) when taking evidence-informed strategies to injury prevention interventions (Pike et al., 2015; Tator, 2012).

- Epidemiology involves conducting research to gain precise knowledge of how injuries like concussion happen within a given sport. While some characteristics like age, biological sex or previous concussion history have been shown to affect risk and recovery times, understanding these “non-modifiable risk factors” is still important for guiding interventions and strategies (Tsushima et al., 2019).

- Evaluation involves monitoring, assessing and reviewing injury prevention programs and strategies to ensure their effectiveness, make adjustments, and show impact. This critical step includes collecting information that can improve and sustain the use of the intervention.

A “sequence of prevention” model for injury research

In 1992, Van Mechelen et al. described a “sequence of prevention” model for injury research, which others have built and expanded upon to guide modern public health initiatives for injury prevention (Pike et al., 2015). Grounded in this sequence of prevention model, the Canadian Injury Prevention Resource outlines 5 functional elements to successfully help prevent injuries:

In 1992, Van Mechelen et al. described a “sequence of prevention” model for injury research, which others have built and expanded upon to guide modern public health initiatives for injury prevention (Pike et al., 2015). Grounded in this sequence of prevention model, the Canadian Injury Prevention Resource outlines 5 functional elements to successfully help prevent injuries:

- Step 1: “Surveillance,” to identify and describe the extent of the sport injury problem.

- Step 2: “Risk and protective factors,” to identify the causes and mechanisms contributing to the risk of injury.

- Step 3: “Selecting and designing an intervention,” to develop measures that are likely to reduce the risk or severity of the sport injury.

- Step 4: “Program and policy implementation,” to apply evidence-based prevention strategies to reduce the risk of injury.

- Step 5: “Evaluation and monitoring,” to plan tangible ways in which to analyze and determine the effectiveness of the intervention.

Step 5 is often overlooked. However, it’s extremely important in figuring out whether an intervention has been successful in reducing injury risk. This frequently means revisiting Step 1 to re-identify the extent of the injury (Tator, 2012, Van Mechelen, 1992). This evaluation process is, ideally, an ongoing component of the initial Step 1 process rather than a separate step altogether.

It’s also important to note that these 5 steps don’t have to be completed in order. Since sport organizations often have limited resources, they may need to adapt to real-world circumstances to make efficient use of their time and efforts. To do so, sport organizations should focus on developing strategies and interventions that are both targeted and sport–specific for reducing the risk of concussion (Pike et al., 2015; Tator, 2012).

Concussion prevention research with Volleyball Canada

Although concussions happen in volleyball, there’s been little evidence-based research informing prevention strategies in this sport. Using the sequence of prevention model, Volleyball Canada set out to understand injury rates (Step 1) and identify specific risk factors and injury mechanisms (Step 2) for concussion among its youth club athletes (aged 14 to 19).

Club athletes compete provincially and nationally, with the season beginning in the fall, and ending each May with Volleyball Canada’s National Championships. With the help of researchers from the Sport Injury Prevention Research Centre (SIPRC) at the University of Calgary, a survey on Canadian youth volleyball athletes, from 2016 to 2018, helped identify rates of concussion, risk factors and injury mechanisms (Meeuwisse et al., 2017). Additionally, the 2018 Volleyball Canada National Championships brought together 9500 athletes and 2000 coaches from all age classes, to one location, presenting us with a unique opportunity to gather extensive epidemiological data on concussion injuries and risk factors.

The SIPRC study’s results showed that most concussions in youth volleyball were caused because of ball-to-head contacts (57%) and the majority (62%) of these occurred during practice or warm-ups. This meant that a large proportion of concussions were from non-competitive, controlled environments, which could be specifically targeted for intervention (Meeuwisse et al., 2017). Using this information, Volleyball Canada developed measures (Step 3) to minimize the risk of ball-to-head contact during these controllable environments (specifically, pre-game warm-up routines).

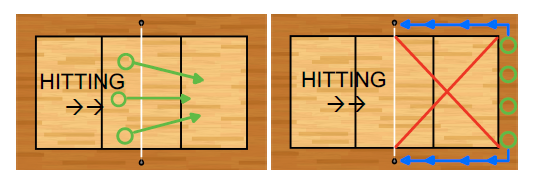

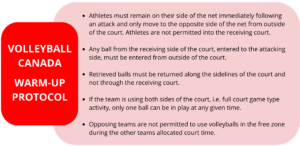

For example, during the standard hitting warm-up routine, a player would attack a ball over the net and immediately run under the net to retrieve the ball. This created a high-risk situation since it was more than likely that this athlete would be struck in the head by the next ball being hit by a teammate. To reduce the incidence of concussions during warm-up, Volleyball Canada introduced a new rule in 2018, which disallowed athletes from running under the net and over to the opposite side of the court to retrieve their ball during the standard hitting warm-up routine (Step 4).

Most provincial sport organizations adopted this new “Warm-up Protocol” rule for their 2019 competitive club season. Volleyball Canada enforced it at its national championships.

Most provincial sport organizations adopted this new “Warm-up Protocol” rule for their 2019 competitive club season. Volleyball Canada enforced it at its national championships.

To tackle Step 5, Volleyball Canada has been actively conducting new studies to evaluate how effective this hitting warm-up rule change has been on reducing concussion rates. The COVID-19 pandemic and lack of competition since 2019 has delayed data collection and analyses. However, initial results suggest that the odds of reporting a concussion during the pre-game hitting warm-up routine remain unchanged since implementing the 2018 rule change.

In re-evaluating the risk of concussion sustained during warm-ups, interestingly, youth volleyball athletes have reported more concussions occurring during the unstructured portion of the pre-game team warm-up. This usually involves players using a ball to rally one-on-one with a partner, or more commonly known in volleyball as “pepper.” This highlights the importance of collecting data and re-evaluating the effectiveness of injury prevention interventions, as new information can continue to fill the knowledge gaps in concussion injury risks and inform future strategies.

Lessons learned and next steps

Though the process is ongoing, Volleyball Canada remains committed to using data and evidence-informed approaches to develop strategies for reducing concussion risks. However, this process is often difficult and resource-intensive for sport organizations. For example, competing priorities, possible resistance to change or new methods, or simply a lack of time, capacity or expertise, are all challenges that face sport organizations when investing in an evidence-informed approach to injury prevention (Pike et al., 2015).

What were some of the important lessons Volleyball Canada learned from its concussion prevention strategies to date?

1. Get creative and innovate

The gathering of quality epidemiological data is both time-consuming and difficult, especially at a national level. As this describes Step 1 of the 5-step process, investing in the resources to help understand the entire scope of the problem, can be a daunting first step.

Consistent data collection allows for assessment of historical trends, or retrospective analysis of the effects that other equipment, rule or policy changes may have on concussion rates (whether the changes are intentional or not)!

Therefore, it’s ideal to collect this type of epidemiological data as part of the membership or event registration process. Starting in fall 2021, Volleyball Canada’s new virtual registration systemwill give the organization another way to potentially help facilitate future information-gathering processes.

2. Build partnerships

With limited resources for research initiatives, partnering with external research or community groups can increase a sport organization’s capacity to conduct concussion injury prevention work. Developing initiatives with these partners, such as universities and hospitals, can help sport organizations gain access to trained staff capable of taking on some of the research burden.

These external groups may even have similar mandates as the sport organization’s injury prevention goals. For example, the University of Calgary SIPRC focuses on working with community partners to reduce the risk of injury in sport and recreation, with a particular emphasis on preventing youth injuries.

3. Engage in ongoing evaluation

By gaining sport-specific knowledge about how concussions occur and where the highest risks exist will guide and direct the development of specific interventions and strategies. Learning that concussions primarily occurred from ball-to-head contact within controlled environments helped Volleyball Canada adopt rule changes to reduce the risk of exposure to that mechanism.

However, equally important is the ongoing re-evaluation process, which continues to provide data on the effectiveness of this rule change. Interventions may or may not work, or may take some time to deliver tangible results. Without this re-evaluation process, sport organizations can’t know whether an intervention has been effective or successful in reducing the risks for concussion injury.

It’s important to consider incorporating this re-evaluation process right from the start of Step 1. That way the continual evidence-based approach can be supported by the initial efforts and infrastructure of setting up data collection and information-gathering measures.

Conclusion

“Although we have come a long way in understanding concussions in volleyball, there is still much more to do. We are still working diligently on the establishment of an effective and efficient surveillance system. Once we get to that in place, developing and assessing interventions strategies will be the easy part.”

Kerry Macdonald, Director of Sport Science, Medicine and Innovation at Volleyball Canada

Understanding the extent of the problem and identifying the factors that create concussion injury risk is key to implementing effective prevention strategies. For sport organizations, these strategies should be targeted and sport-specific, because every sport may have unique injury mechanisms that contribute to concussion risk. Alongside existing educational and technological strategies, an evidence-informed approach is the most effective way of developing further preventative measures that protect athletes and reduce the burden of concussion injury.