Canadian track cyclist Georgia Simmerling is the first, and only, Canadian to compete in three different sports at three different Olympic Games: alpine skiing (Vancouver 2010), ski-cross (Sochi 2014) and track cycling (Rio 2016). After claiming bronze in the women’s cycling team pursuit in Rio, Simmerling will take to the track once again in Tokyo.

Can the Olympic and Paralympic Games influence the sport participation of youth in the host communities? Research suggests that participation impacts may be most likely among youth populations, active and inspired spectators, and within communities that are home to event venues and medalists.

Although Olympic athletes are known for their meticulous pre-competition routines, many aspects of competition are out of their control. For example, research shows that Olympic swimmers have 0.32% improved performance when they race in the evening compared to in the morning—showing that time of day could be enough to make or break a podium performance.

“As athletes, we’re being taken more seriously and senior leaders are asking for our opinions – not because they feel they have to check a box, but because they believe we have something important to bring to the table.” – Seyi Smith, Chair of the COC’s Athletes’ Commission and two-time Olympian, reflects on the rise of the athlete voice in a special edition of the SIRCuit.

Fourteen-year-old Toronto-based swimmer Summer McIntosh is Canada’s youngest Olympian in Tokyo. In June, the Grade 9 student won the 200m freestyle at the Canadian Olympic Trials, beating out 2016 Olympic champion Penny Oleksiak. Make sure to watch this rising star and the rest of Canada’s Olympic swim team in action until August 1 in Tokyo!

The Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games officially open today and continue through Sunday, August 8. With 370 athletes and 131 coaches attending, this is the largest contingent of Canadian athletes at an Olympic Games since Los Angeles 1984.

Tokyo last hosted the Olympic Games in 1964. At that edition of the Games, Canada’s only gold-medalists were men’s pair rowers Roger Jackson and George Hungerford. As Canada’s largest rowing team in 25 years gears up for Tokyo 2020, Kai Langerfeld and Conlin McCabe will be looking to repeat history in the same event. The Olympic rowing regatta kicks off on July 23rd.

Highlights

- Despite its status as an Olympic city, attitudes towards sport and recreation initiatives in Calgary have been mixed.

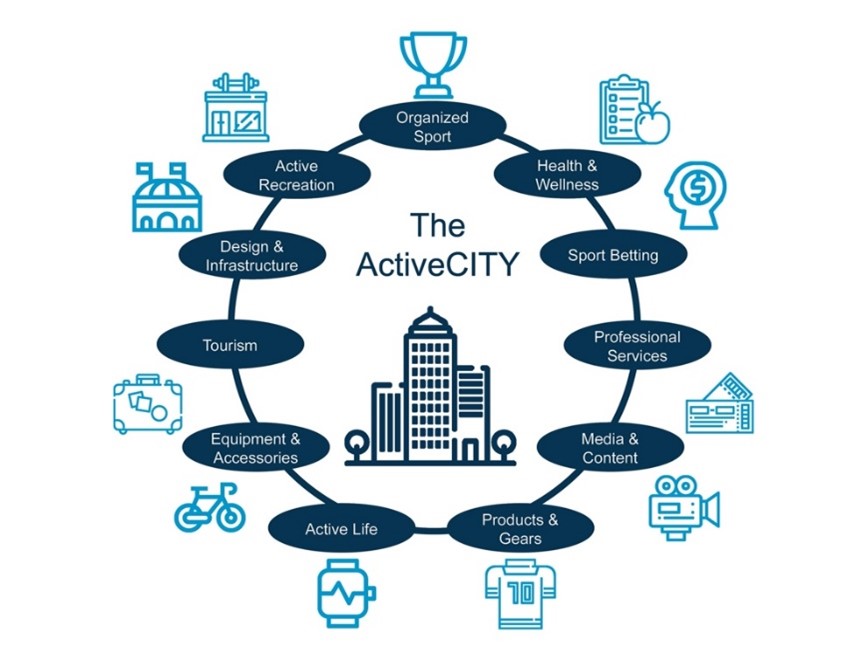

- A city’s active economy includes all organizations and individuals who directly or indirectly contribute to the development and delivery of sport and active recreation experiences.

- Calgary’s active economy includes 95% of the 1.5 million people living in the Calgary region, incorporating 4000 enterprises, employing 43 000 people, and contributing $3.3 billion to the regional economy.

- The ActiveCITY Collective is a collaboration of not-for-profit, for-profit, and public-sector organizations as well as individuals engaged in Calgary’s regional active economy. It was created to leverage Calgary’s active economy for regional growth and prosperity.

- ActiveCITY Collective’s Playbook 2030 aims to establish a framework to maximize the impact of Calgary’s regional active economy on both individual and community well-being, and in doing so, transform Calgary into Canada’s most livable region.

In November 2018, Calgarians participated in a plebiscite to decide if the city should proceed with a bid to host the 2026 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Calgary’s shot at hosting its second Olympics and first Paralympics came to an end as 56.4% opposed bidding. This was perhaps the final straw in what we, Calgary-based academics at Mount Royal University, had seen as a trend: sport and recreation were being minimized and underappreciated in Calgary.

Another example was the ongoing debate and public pushback about whether Calgary should fund a field house, a conversation that started in the 1960s. Calgary is the only major Canadian city without such a facility. Other examples included the moral outrage over the expansion of separated bike lanes, the city considering closing public golf courses, and WinSport shuttering the bobsled, skeleton and luge run, a legacy track of the 1988 Olympic Games.

The past few years have been volatile for Calgary’s sport and recreation sector. Every week, it seemed, we debated and questioned our commitment to being a city that promoted and supported an active life. We considered Calgarians as members of an Olympic city, one that embraced, celebrated and aspired to lead in sport and recreation, as well as health and wellness. But was this still true?

Defining a ‘great sport city’

In January 2019, we assigned a question to undergraduate students who were studying sport and recreation management: Is Calgary a great sport city? We gave students latitude in how they defined a great sport city, with ideas ranging from the number of fans attending professional sport events to the number of world-class events hosted by the city. Students presented their findings to local sport leaders at the Canadian Sport Institute Calgary. When asked to rank Calgary against these findings, the results of the student analyses were mixed. Despite its status as an Olympic city, Calgary fell in the middle of most rankings.

After further considering this question, we gathered 50 sport leaders from Calgary and the surrounding area for (what we called) the Sport Business Roundtable, in the Mount Royal University library. Delegates were from grassroots clubs to high-performance sport, including representation from ski hills, eSport, and postsecondary athletics and recreation. We spent the morning debating the future of sport. This included a welcoming plea from City Councillor and mayoral candidate Jyoti Gondek asking the sport community to provide a meaningful business case for why taxpayers should support and engage in sport.

Three takeaways emerged:

- We concluded that “sport business” was the wrong term to describe ourselves. We collectively decided to start using “active city.”

- The people we invited didn’t really know each other. We had assumed they would already know one another.

- This group genuinely wanted to connect and collect, which was reaffirmed when most delegates stayed well past the session’s ending time. And lunch wasn’t even provided!

From this meeting, we concluded that Calgary’s rich regional active ecosystem was fragmented and inefficient. The result was its contribution to Calgary’s economic, human, social and environmental prosperity was being underleveraged.

The ActiveCITY Collective

The response was to create the ActiveCITY Collective: a collaboration of not-for-profit, for-profit and public-sector organizations as well as individuals engaged in Calgary’s regional active economy. Our goal was to transform Calgary into Canada’s most livable region through its active economy, and do this by facilitating collaboration, debate, learning and connection. The Collective would need to be independent and inclusive. It should be anchored in a systems perspective and work towards generating community prosperity. Finally, the Collective must use evidence and not anecdotes.

The ActiveCITY Collective was built upon the idea of an active economy that was grounded in 2 models. First, the New Zealand Model of Community Prosperity (also known as Living Standards Framework), which recognizes that benefits can be felt in the human, economic, environment and social spheres (New Zealand Treasury, 2018). The second model was Dr. Richard Florida’s idea of a creative class. In the early 2000s, Florida noted that “Beneath the surface, unnoticed by many, an even deeper force was at work—the rise of creativity as a fundamental economic driver, and the rise of a new social class, the Creative Class” (Florida, 2002). Could a similar argument be made about an active economy? Could Calgary and region mimic the growth of cities such as Nashville, which hung its hat on the idea of a creative class?

Nashville wasn’t an accident. Its creative ecosystem was built and nurtured for more than 100 years. It harnessed all its resources, from universities to musicians to entrepreneurs, to build a city and region that would attract and retain the best and the brightest. In 2006, Nashville included 80 record labels, 100 music publishers, 150 recording studios, 17 of the top 25 country music artists, and 39 fully integrated collaborative organizations (Raines & Brown, 2006). Could Calgary and region do the same thing but from an active economy lens?

Therefore, we began the process of trying to map and understand the breadth and depth of the active economy.

Mapping the active economy

The process of mapping the active economy included a series of steps that started with the creation of categories of organizations. This was followed by groupings of individual participants and concluded with a mapping of their interrelationships.

The first step was to create groupings that would enable measurement and a better understanding about what types of organizations constitute an active economy. We created 11 categories including organized sport, health and wellness, sport betting, professional services, media and content, products and gear, active life, equipment and accessories, tourism, design and infrastructure, and active recreation.

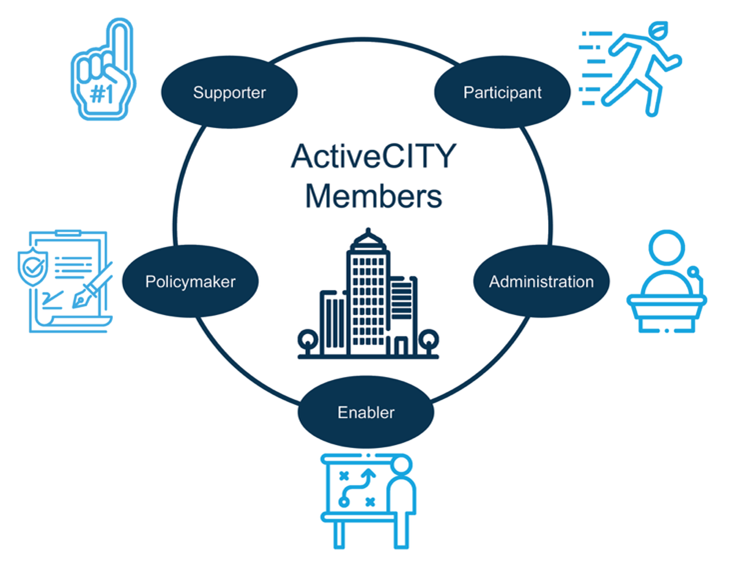

The second step was trying to understand the people in the active economy. Every individual or organization with an interest in or impacted by the active economy was considered an important player. This includes all forms of engagement, including professional or volunteer. Therefore, the ActiveCITY Collective defined engagement in 5 categories: participant, administration, enabler, policymaker and supporter. An individual or organization may encompass one or more forms of engagement.

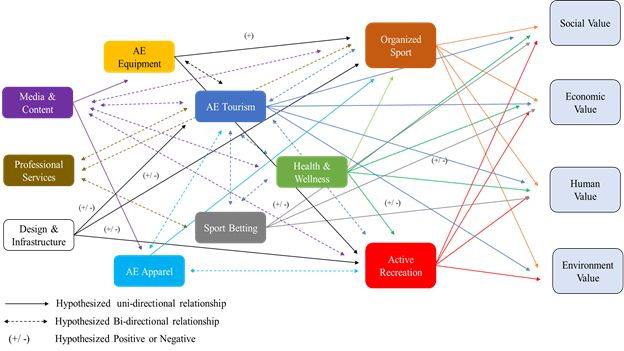

In the third step, we attempted to map the interrelationships of the various factors of the active economy. The categories that we noted earlier didn’t operate in isolation. The potential benefits from the active economy would require interrelationships among the categories. While conceptual, our map showed the series of hypothesized links between different aspects of the ecosystem. For example, environmental value can be gained through the connections from design and infrastructure through active recreation. While complex, this map was central to our understanding of where and how to allocate resources that would generate maximum return on the public’s investment. This was answering City Councillor Gondek’s call for action at the Sport Business Roundtable.

During the mapping phase, we cajoled and recruited a broad cross-section of leaders in which to debate, discuss and consider how the sector could better work together. Due to overwhelming interest from would-be participants in the lead-up to a fall 2019 summit, the venue had to be changed 3 times! The summit was eventually held at WinSport with 300 participants and a waiting list.

Clearly, the idea of an active economy had struck a nerve. After launching an ActiveCITY website, we began to measure the active economy through research. With a team of students and colleagues, we enacted Calgary’s largest public engagement strategy, collecting input from more than 23 000 individuals. In addition, we hosted 20 virtual ‘FutureMaking’ Forums on topics ranging from eSport to First Nations and Indigenous persons in the active economy. We recorded more than 25 podcasts with community leaders discussing the future of Calgary’s active economy. We also helped coordinate province-wide longitudinal research on the intersection of arts, culture, and sports and recreation in a pandemic and post-pandemic environment. We determined that the active economy includes 95% of the 1.5 million people living in the Calgary region, incorporating 4000 enterprises, employing 43 000 people, and contributing $3.3 billion to the regional economy.

This led to the creation of Playbook 2030 and provided direction for Calgary’s support of the active economy.

From pandemic to Playbook 2030

The impact of COVID‑19 can’t be understated. The pandemic is causing seismic economic, human, and social costs to our city and region. Since travel and large gatherings are restricted, our outdoor recreation facilities face unprecedented capacity pressure. This has only accelerated the urgency of creating an integrated master plan for our regional active economy. The resulting master plan is known as Playbook 2030. It’s anchored in a strategic framework that will harmonize resources from across the commercial, social, and public sectors to strengthen our economic, human, social, and environmental prosperity. While Calgary is facing unforeseen challenges, Playbook 2030 identifies unrealized opportunities and unique advantages. The time is right to deliver a renewed vision of our city and region that leverages our greatest natural resource, an active economy.

We presented Playbook 2030 to the community during a virtual online summit on December 2 and 3, 2020. The theme was From Pandemic to Playbook 2030. At the summit, we reviewed the path from the devastation of COVID‑19 to the vision of a world-leading active economy as detailed in the Playbook.

In the press release following the summit, Cynthia Watson, the newly named co-chair for ActiveCITY and Chief Evolution Officer of Vivo for Healthier Generations, noted that “Calgarians challenged us in November 2018 to think differently. They wanted us to look forward, not backward. With the guidance of thousands of Calgarians and insight and inspiration from global leaders, we have defined a city that is not only a player, but a leader in the $3 trillion active economy.”

The Playbook 2030 plan was based on 6 pillars: a shared vision, embedded in life, built on community, innovate and grow, drive sustainability, and inspire others. The plan also returned to the New Zealand Model of Community Prosperity, including links to the human, social, economic, and environmental impacts. For example, under economic impact we referenced a study for the British Columbia Ministry of Health Planning that estimates an annual cost savings of $49.4 million if physical inactivity could be reduced 10 percent.

Conclusion

We’ve attempted to create an ActiveCITY that is inclusive. It brings together volunteers, coaches, entrepreneurs, educators, policymakers, parents and guardians, in areas ranging from tai chi and gardening to soccer and emerging sport technology. What we share is a passion for the unique role that the active economy can play in moving our city and region forward.

For other cities and regions attempting to mirror this process, we offer the current steps being taken to implement our Playbook. The first is to transition the ActiveCITY Collective into a more formal structure. The second is to establish a harmonized governance model for implementing the program. The third step is to deliver a few quick wins with research studies showing benefits of how collaboration has worked. And the final step is to prioritize high-impact, ecosystem projects for Playbook 2030.

To support the implementation of Playbook 2030, the ActiveCITY collective has received a 2-year grant from the Government of Alberta’s Civil Society Fund. The goal of Playbook 2030 is to establish a framework to maximize the impact of Calgary’s regional active economy on both individual and community well-being, and in doing, transform Calgary into Canada’s most livable region. At times, the scope and depth of Playbook 2030 may feel daunting. For this reason, we think it is best to consider Playbook 2030 as a critical step in a ten-year master business plan for Calgary’s regional active economy. As a complex $3.3 billion business that incorporates 4000 enterprises across 10 sectors and impacts 1.3 million people, the business plan must be systematic, rigorous and evidence-based.

Playbook 2030 is uniquely Calgary. Its approach combines academic rigour, community spirit, entrepreneurial optimism, and a belief that this is a promotable differentiator that defines our civic culture and identity for a generation. We’re facing challenges unforeseen and unprecedented. This is a necessary and opportunistic time to be contemplating a new vision for our city and region, based on collaboration and leveraging our greatest natural resource, our active economy.

Highlights

- After a one-year postponement, the 2020 Summer Olympic and Paralympic Games in Tokyo, Japan will be held just 6 months before the 2022 Winter Games kick off in Beijing, China.

- The postponement of Tokyo 2020 created a unique set of challenges for the Canadian Olympic Committee and Canadian Paralympic Committee, who are also preparing for Beijing 2022.

- Strict COVID-19 guidelines and countermeasures are in place to ensure health and safety are top priority at the Games.

- Finding new ways to communicate and connect has been an important strategy for members of the Canadian Olympic Committee and Canadian Paralympic Committee.

- There will be a greater focus on mental health and well-being for all attending the Games.

SIRC asked former sports journalist Teddy Katz to sit down (virtually) with leaders from the Canadian Olympic Committee (COC) and Canadian Paralympic Committee (CPC) for a behind-the-scenes look at the challenges of preparing for 2 Olympic and Paralympic Games amid a global pandemic. After a one-year postponement, the Summer Games, set to be held in Tokyo, Japan, will be held just 6 months before the Winter Games kick off in Beijing, China.

During the conversations with COC and CPC officials, a few key themes emerged for these Games like none we’ve ever seen before. This article shares that athletes, coaches and staff have faced enormous challenges and have had to deal in new ways with risk, uncertainty, safety, communication, and mental health.

The risks: To go or not to go

Ever since the Games were postponed in 2020, there have been lingering questions about carrying on with them and whether it was worth the risk. The International Olympic Committee and International Paralympic Committee have been working closely with experts from the World Health Organization guiding them to find a way to have the Games take place safely. But the Japanese public has been jittery. The roll-out of vaccinations has been slow in Japan, and polls show many people oppose the Games happening mid-pandemic. With 15 000 Olympic and Paralympic athletes due to arrive this summer, along with thousands more media, sponsors and other stakeholders, some have concerns that the Games will become a petri dish for the virus.

Grace Dafoe, a member of Canada’s national development team for skeleton, understands those concerns better than most. Dafoe contracted COVID‑19 in April from a close contact while she was training in Calgary. She says it “walloped” her. She felt incredible fatigue, and had a horrible dry cough and raging headaches. “It was scary and unlike anything I’ve ever felt before.”

Still Dafoe isn’t worried about the Games going ahead. “There’s a risk in going to the grocery store at home in Calgary. There’s risk everywhere. We just have to accept that.” She says her concerns were eased when the Canadian Olympic and Paralympic Committees made the dramatic move last year to withdraw from the Games in 2020.

“One of the most comforting things for me was actually when Canada was the first to pull out of Tokyo. I think that sent a message to me as a winter athlete as well that they’re going to have our best interests in mind when it comes to our health.”

Uncertainty: A pre-Games like no other

It’s never been a more challenging time for Canada’s Olympic and Paralympic athletes, what with the Tokyo postponement, athletes scrambling to train from home and unable to travel, cancelled qualifying events, and athletes with disabilities unable to get classified. Karen O’Neill, Chief Executive Officer (CEO) of the CPC, says everybody is feeling unprecedented stress. “I don’t think there’s ever been such a sustained period where our coaches, our athletes and sport members have been tested so much and been asked to perform so many accommodations.”

David Shoemaker, CEO of the COC, and Marnie McBean, former Olympic rower and the Canadian Olympic Team’s Chef de Mission in Tokyo, co-hosted a Canadian Club luncheon, held virtually in May. They took turns asking each other questions and speaking to the difficult lead-up for the Games.

“Tokyo was going to be these really easy Games when they got them,” McBean reminded Shoemaker and the audience. The IOC was turning the Games over to what they referred to as “a safe pair of hands.” She added, they wanted to avoid some of the chaos they dealt with in previous Games in Russia, with exorbitant costs, and Brazil, with its financial troubles, Zika virus and other issues.

“Tokyo was going to be these really easy Games when they got them,” McBean reminded Shoemaker and the audience. The IOC was turning the Games over to what they referred to as “a safe pair of hands.” She added, they wanted to avoid some of the chaos they dealt with in previous Games in Russia, with exorbitant costs, and Brazil, with its financial troubles, Zika virus and other issues.

The reality is that the pandemic has turned these Games into one of the most challenging ever. “These bumps in the road, in some cases huge potholes, are things that we need to assume are going to happen on this journey to Tokyo,” Shoemaker says.

Every athlete, every sport, has been impacted in their own way. McBean says the swimmers, for example, have been out of the water and unable to train the way they normally would for 120 days because of the lockdown of facilties during the pandemic. “There’s an Olympic thing happening every day. And there’s Olympic things not happening every day. It’s been really challenging.”

“But that’s what Olympism is, right? That’s the whole idea of why people go, ‘Oh, that’s a Herculean or an Olympic sized task’. It’s always been hard. It’s never been a straight line to Olympic gold.”

The uncertainty that’s been difficult to manage will continue throughout the Games, says Catherine Gosselin-Després, who is the Executive Director of Sport for the CPC. At Games time, Tokyo organizers are employing strict COVID‑19 guidelines to limit everybody’s movement. They’ll go to their events and then back to the Olympic Village. “We’ve been working with the national sport organizations trying to explain the environment. But obviously, none of us have lived this before.”

The uncertainty that’s been difficult to manage will continue throughout the Games, says Catherine Gosselin-Després, who is the Executive Director of Sport for the CPC. At Games time, Tokyo organizers are employing strict COVID‑19 guidelines to limit everybody’s movement. They’ll go to their events and then back to the Olympic Village. “We’ve been working with the national sport organizations trying to explain the environment. But obviously, none of us have lived this before.”

At the time of the interviews with fewer than 60 days to go to the Games, Canada’s Olympic and Paralympic planners usually know almost every detail right down to the size of the doorknobs for the 400 or so athletes who will be going for the Olympics and 130 athletes headed to the Paralympics. Typically, planners would have made many trips to the site to prepare for the Games. But that hasn’t been the case during the pandemic. With the Winter Games in Beijing kicking off just 6 months after the Summer Games in Tokyo, planners will cut and paste to try to reuse many of their Tokyo plans for Beijing.

Céline DesLauriers, Senior Manager of Games at the COC, says the master plan is 20 000 lines long. Her logistics team has gone from using Excel spreadsheets to an online software program where they can track changes on the fly. Instead of shipping the teams’ necessary sports gear and equipment, the way they have in the past, they’re chartering a cargo plane.

Another tricky part comes with travel arrangements. With the new COVID‑19 guidelines, athletes can only check into the Athletes’ Village up to 7 days before they compete. They must leave within 48 hours after their competition ends. For a team sport, that will require juggling for everyone involved when teams get eliminated.

“Normally, a couple of months out to the opening of the Village, the national sport organizations pretty much know who’s coming and everything. They’re just waiting for the final qualification. What we’re seeing is right now it’s being pushed till the very last seconds. We’re just learning to be nimble and adaptable,” DesLauriers says.

The priority: Health and safety

The COC and CPC aren’t releasing their usual performance benchmarks that normally proceed the Games. While they know most athletes will be aiming to get on the podium, they don’t want anybody feeling any added pressure. According to the CPC’s O’Neill, the overall well-being of Team Canada is the primary goal in Tokyo.

“What keeps me up at night, it’s my personal and professional commitment to the responsibility of ensuring that Team Canada is supported. The primary objective is that everyone is safe, healthy, both heading into Tokyo, during the Games and coming back afterwards.”

The COC’s Shoemaker says that includes keeping people in the host country safe as well. Until now, Japan has done a pretty good job of minimizing infections from the virus. With more than three times Canada’s population, Japan has had half our number of cases and deaths. And there are many COVID‑19 countermeasures to keep things that way during the Games. These include two negative tests prior to going, testing everybody daily upon arrival, and keeping everybody contained in the Village or at competition venues.

“Everyone should wipe clean from their minds what they think an opening ceremony or what a competition will look like. There will be no overseas spectators. There won’t be friends and family. We won’t have a Canada Olympic House in Tokyo. That doesn’t guarantee the complete safety but we’re doing our absolute best to prioritize the health of everybody involved,” Shoemaker says.

The CPC’s Gosselin-Després says many athletes have received their first vaccine and breathed a sigh of relief with the news in May that Pfizer would donate 2 doses for every athlete who wants to be vaccinated. “For us, that was key. I think the athletes would have probably had questions if there was just one dose. But now with the announcement, I think that’ll help everyone.” However, the Pfizer vaccine isn’t approved in all countries and there still could be positive COVID‑19 tests even among those who have been vaccinated.

Stephanie Dixon, who is a former Paralympic star athlete and now Chef de Mission for the CPC in Tokyo, says COVID‑19 just adds to the usual stress of performing at the Games. “I don’t think we can underestimate that level of stress,” Dixon says. “People are going to be nervous, if they feel a tickle in their throat. Every single one of us in the world has suddenly given new meaning to having a tickle in the throat or to a runny nose.”

The CPC and COC always plan for many different scenarios. For Tokyo, that includes a number of plans specifically for COVID‑19. For example, what to do if there’s a positive case? And what happens if there’s a false positive that forces somebody to miss their event? These are among the new questions they need to consider.

Finding new ways to communicate and connect

Every media story out of Japan has raised doubts about the Games and added to the uncertainty. It’s been hard to separate fact from fiction. That’s why a fundamental part of the CPC and COC plans for Tokyo and Beijing has become communicating and providing constant updates with the latest facts for all stakeholders. Since the fall, both committees have adopted a crisis communications approach.

In a crisis, communications experts say it’s important for leaders to clearly state what they know, what they don’t know, and when they hope to provide an update on what they don’t know. DesLauriers of the COC says, “That’s exactly the strategy we’ve taken in all of our communications.”

As Chef de Missions, Dixon and McBean have been meeting virtually every few weeks with athletes and other stakeholders. “This is the most engagement with athletes that I’ve ever seen prior to the Games,” says Dixon. “I think it’s important we’re getting them into a virtual, figurative room together because they can hear from each other what each has been going through. It helps us as a support staff really see into the minds of the athletes and see what they need from us.”

Before the pandemic, McBean expected to be travelling the country and providing a different kind of motivation. “Suddenly my interactions with the team and the conversations we were having with the athletes weren’t about this fun ambitious management to the podium. It was more life management.”

McBean advised the different teams and athletes that the fear and doubt they might be feeling are part of every athlete’s path. She told them not to worry about the big things. Focus on the little things that make you better and that’s when great things happen.

Dixon says at Games time, one of the issues they’re dealing with revolves around the team being told they must social distance when they aren’t competing. “One of the primary measures is to stay away from each other. If we can’t physically get close to one another, we can’t be cheering and singing. How do we get a sense of team unity?”

She says they’re looking for creative ways to connect the team. They’re thinking of having athletes post sticky notes with messages for one another, or doing virtual team recognition and medal ceremonies every day in Tokyo.

“At the end of the day, when athletes isolate after their events and go back to their rooms, we’re thinking about how we can break down those isolation walls in a virtual way.”

A focus on mental health

The prolonged sense of uncertainty added to the usual stress of the Games has created fertile ground for anxiety. It’s taking a toll on athletes as it has for the rest of society. Susan Cockle is a psychologist who is working with the CPC. She’ll be on site in Tokyo as the Mental Health Lead. It’s the first time the CPC has ever had one at the Games.

She says anxiety is actually the body and brain’s way of protecting us as humans. When things are uncertain, we go on high alert. “It’s like our emotional psychological furnace has been running on high for a while. When, our anxiety – our furnace – has been running on high, it doesn’t take much for it to break down,” says Cockle. “That’s why we need some ongoing service to the furnace, why we want to do some mental health mitigation. We want to do some prevention so that we can have that furnace run on a lower temperature, and not burn out.”

Normalizing the conversation and creating social support around mental health and wellness are 2 of the most important ways to do that. Shoemaker says it’s been a key focus for the COC too. “We have found it’s very important for us as we are delivering our team to two Games in six months to be very focused on how people are doing. I have found myself asking questions I would have never dreamt of asking a couple of years ago: ‘How are you doing and how are you feeling?’ and getting people to talk and open up.”

Cockle says checking in is important and recommends asking specific questions to help people focus their responses. “How are you doing with COVID‑19 is a big question. If you can make that question a little more contained, then people are more likely to answer more genuinely,” she says. “If you actually say, ‘how are you doing today’, you’re more likely to get an emotion. That’s what we want. We want those types of responses to be real and out in the open. Normalizing that can make people feel less alone.”

It’s not just the athletes who they’re concerned about for mental health, according to the COC’s DesLauriers. “It’s also for all the support staff and the mission team that will be on site. As an example, I’ll be in Tokyo 44 days. I’m not used to wearing a mask every day, having to do a test every day, doing the work that is normally pretty hard, amplified with all of the COVID‑19 countermeasures and restrictions that will be put on us.”

If things go sideways, both the COC and CPC have put plans in place with extra support, more reaching out and more points of contact. Athletes will know about extra resources from Game Plan or from the Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport.

Cockle says mental performance consultants are also helping with mental health preparation. Penny Werthner is one of them. She’s assisting both the Olympic Athletics Team and the Paralympic Athletics Team among other athletes. Werthner always works with athletes and teams on distraction control and focus, emotional agility, dealing with disappointment and embracing chaos and uncertainty.

Werthner says COVID‑19 has added a few new areas. “There will presumably be distractions from people testing positive whether you’ve been vaccinated or not. That’s a whole added layer that we’ve never faced before.” Werthner says talking about it ahead of time helps athletes prepare if it does happen.

She says managing isolation is another new area. “In previous Olympics, athletes would have friends and family there. For many, that’s a comforting thing. They can actually escape the Olympics for a day or so.” But athletes won’t have that same luxury in Tokyo. “There’s presumably no escape. You’re not going to be able to go around the city in Tokyo and do something fun,” says Werthner.

That’s a concern for the CPC’s Dixon. “There’s so much stress and tension that builds up in the lead-up to the Olympics and Paralympics. Whether it is the performance you were looking for or not, you always need a release afterwards.” After years of preparation, Dixon worries many athletes may miss out on the vibe and hype that normally comes from connecting with teammates and performing in front of fans in the stands. That’s why she says the team needs to address mental health before, during and after the Games, and she is happy to see the support being offered. “We’ve never been so focused on mental health and wellness at the Games,” she says.

But despite the challenges of preparing for these atypical Olympic and Paralympic Games, Dixon believes the world will see strength, grit and determination of the human spirit in a way we’ve never witnessed before.

“We will see great performances brought and fueled from these great challenges and adversity. It’s incredible what we can accomplish when we’re given no choice.”

The Summer 2021 SIRCuit is now available!

The SIRCuit is designed to highlight important research and insights to advance the Canadian sport system. With the summer Olympic and Paralympic Games in Tokyo on the horizon and the winter Games in Beijing just around the corner, this edition of the SIRCuit dives into issues and trends that will be centre stage at (and after) the Games.