Highlights

- There are several evidence-informed approaches to sport delivery that researchers and sport organizations encourage, and that you can engage with, to promote positive experiences and combat harmful cultures in sport and society

- Quality sport, values-based sport and safe sport are 3 approaches to sport program delivery that are gaining traction and popularity at all levels of sport

- Although they have their differences, each approach recognizes sport as a context where communities and sport participants can gain valuable benefits like promoting morals and principles, healthy development, and fulfilling basic human needs

- In this article, SIRC takes a deep dive into each of these approaches: how researchers and organizations are using them, what the evidence says about them, and tools to help you leverage them

Quality sport. Values-based sport. Safe sport. Positive youth development. Person-centred sport. Athlete-centred sport. Holistic approaches.

These are just a few of the many terms used within the sport sector to discuss the different ways in which sport delivery, programs, and culture are approached. Whether you are new to working in sport or an experienced staff member, participant, or even sport parent, it’s not uncommon to hear these terms used and feel a sense of confusion. What do they mean? Why are they important? And most importantly, how can you implement them?

In this article, we explore 3 approaches to sport program delivery that sport researchers and practitioners alike recommend for their potential to optimize the sport experience: Quality sport, values-based sport and safe sport. We define these approaches, what the evidence says about them, and map out how they are similar or different from one another.

Quality sport

Within academic literature, a quality approach to sport participation means ensuring participants view their experiences as enjoyable and satisfying based on their own preferences and values (Evans et coll., 2018). More specifically, researchers define quality participation in sport as repeated exposure to positive experiences, programming, or environments that promote long-term athlete development and participation (Côté et coll., 2014, Yohalem & Wilson-Ahlstrom, 2010).

There is evidence to suggest when an individual’s needs are satisfied and participants are enjoying their sport experiences, they are considerably more likely to continue to participate in sport (Caron et coll., 2019; Ryan & Deci, 2017). With repeated exposure to positive experiences, they will also be more likely to reap the physical, social, and mental benefits of sport participation (Caron et coll., 2019; Martin Ginis et coll., 2017). This means that prioritizing the quality of programming is important for long-term participation and healthy development.

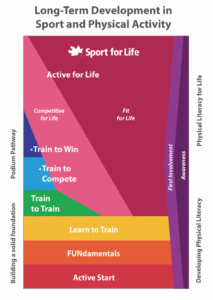

It is important to acknowledge that organizations apply these definitions in their own way or use slightly different language to express their specific quality sport goals. For instance, Sport for Life uses “quality sport” and promotes the Long-Term Development in Sport and Physical Activity (LTD) framework as a guide for achieving positive experiences in sport and physical activity for individuals over the lifespan. According to Sport for Life, quality sport “is developmentally appropriate, safe and inclusive, and well run.” In other words, quality sport is “good programs, led by good people, in good places.”

On the other hand, the Canadian Disability Participation Project (CDPP) promotes “quality participation” in sport and physical activity for people with disabilities. According to the CDPP, “quality participation is achieved when athletes with a disability view their involvement in sport as satisfying and enjoyable, and experience outcomes that they consider important.” To achieve quality participation, participants need repeated and sustained exposure to “quality experiences” over time. Six elements contribute to a quality experience (Martin Ginis et coll., 2017):

- Belongingness (sense of belonging and acceptance from a group)

- Engagement (motivated and focused on activities)

- Achievement (experiencing sense of accomplishment)

- Challenge (feeling appropriately challenged in activities)

- Choice (having independence and input)

- Personal and social meaning (contributing toward meaningful goal)

To support these elements, appropriate conditions in the physical (for example, accessible facilities, access to equipment), social (for example, coach or instructor knowledge, friendships, family support), and program (for example, program size, funding support) environments need to be in place (Evans et coll., 2018). While the CDPP’s framework was developed for people with disabilities, it can be applied to sport participants in all contexts.

A variety of practical tools and resources have been created to guide sport organizations and program leaders in fostering quality sport programs. For example, Sport for Life creating a Quality Sport Checklist and a Quality Sport Guide for communities and clubs. Alternatively, the CDPP created the Blueprint for Building Quality Participation in Sport as a tool to help sport programmers foster quality experiences for children, youth and adults with disabilities, which leads to quality participation over time. The Blueprint has also been tailored for children and youth with intellectual disabilities and Autism Spectrum Disorder. Ultimately, creating quality sport experiences involves understanding your programs and athletes’ unique needs to help identify what values and program components you should focus on and prioritize.

Values-based sport

The aim of sport delivery that is values-based is to create an environment that encourages values like (but not exclusive to) good character, physical literacy, community and belonging. Another goal of values-based sport is to create good citizens and well-rounded individuals through sport. However, this approach to sport delivery is more explicit in its use of values and morals to achieve its goal when compared to the other approaches described in this article.

Adopting and promoting values in Canadian sport has been advocated by communities and organizations like Collaborative Community Coaching (C3)™, the Sport Law & Strategy Group, the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES), and True Sport.

Of particular note, the CCES is an independent, national, not-for-profit organization committed to making sport better. The CCES does so by working collaboratively to activate a values-based sport system, protecting the integrity of sport from the negative forces of doping and other unethical threats, and advocating for sport that’s fair, safe and open to everyone. True Sport is an initiative of the CCES designed to give people, communities and organizations the means to leverage the benefits of good sport from a platform of shared values and principles. As a values-based sport network leader, the CCES believes that activating the True Sport Principles, on and off the field of play, will contribute to a positive shift in Canadian sport culture.

Values-based approaches operate on the belief that sport has many physical, social and mental benefits but these benefits are not guaranteed by simply participating in sport (Bean et coll., 2018). The 2022 True Sport Report, commissioned by the CCES, recommends that in order for sport to be “good sport,” values and principles need to be put into action (for example, incorporated into policy, practice, and programs) and work together at all times. Informed by recent research, the report suggests that when this occurs, participants and communities alike will benefit.

Despite being advocated for and implemented in organizations for many years, values-based approaches have not yet been investigated extensively in the academic literature. Nevertheless, the goal remains similar to previous approaches discussed—that is, meeting the basic human and developmental needs of participants.

While researchers are still investigating whether the explicit teaching of values is necessary for participants to acquire them (as opposed to them being obtained organically from “good sport”), the morals and principles promoted through values-based sport are universally positive (Bean et coll., 2018).

The key characteristic of values-based approaches to sport programming is that they are intentional and clear with the values and purpose of the activities participants are taking part in. According to Jones and McLenaghen, a good starting point for an organization or club looking to take this approach is to develop a “values-based agreement.” In other words, come together and agree upon your organization’s values and principles and promote them throughout your programming. Part of the CCES values-based education programming also includes a values-based agreement as an essential step in guiding and clarifying your community’s purpose for athletes, coaches and leaders, and meeting the goal of fostering values through your programming.

The CCES provides additional suggestions for those wanting to make a positive difference in their sport and community:

- Know and evaluate your own values and principles

- Purposefully align your decisions and actions with core values and principles

- Make decisions consistent with your personal values and principles, and build accountability to yourself and others

- Be a model of prosocial values and principles, and promote the inclusion of all sport participants

Safe sport

The safe sport movement aims to optimize the sport experience for everyone in sport, including but not limited to administrators, officials, and support staff. To optimize the experience, stakeholders should have the reasonable expectation that the sport environment will not only be free from all forms of maltreatment (for example, abuse, neglect, bullying, harassment, and discrimination), but that it will also:

- be accessible, safe, welcoming, and inclusive

- will contribute to wellbeing

- be enjoyable and respectful of personal goals, and

- provide a sense of achievement.

Safe sport extends beyond the prevention of physical, psychological and social harm to include the promotion of participant rights (Gurgis & Kerr, 2021). According to Gretchen Kerr, an academic expert and a leader in the safe sport movement, the safe sport movement does not intend to abandon athletic results altogether, but rather places emphasis on healthy, safe, and inclusive methods for achieving performance results.

As testimonies continue to surface of discrimination, harassment, abuse, and other forms of maltreatment in sport, the body of literature focused on safe sport and safeguarding in sport has grown substantially. In particular, recent studies have demonstrated how unsafe sport environments and maltreatment are contributing to participants’ mental health concerns and withdrawal from sport (Battaglia et coll., 2022).

For example, in a recent SIRCuit article, a team of researchers (Eric MacIntosh, Alison Doherty and Shannon Kerr) described the findings of a study exploring athletes’ perceptions of safe and unsafe environments in high performance sport. The researchers identified coach and teammate behaviour (like aggression, exclusion, and overstepping boundaries), as well as a lack of resources and inattentive sport system (meaning, lack of accountability, attention, and/or action) as primary contributors to unsafe sporting environments. In contrast, athletes shared that they felt safest when they had a knowledgeable coach, athlete interests were prioritized, regulations were followed, they had access to ancillary support (like, physiotherapy and counselling), and when there was a sense of community among athletes and coaches.

According to experts, adopting a values-based framework where inclusion, safety, fairness, and accessibility are promoted alongside strategies to prevent harm and abuse appears critical to optimizing the experiences of sport participants (Gurgis, 2021). With safe sport in mind, Donnelly and Kerr (2018) recommend that sport organizations engage in the following strategies:

- Ensure everyone in your community is aware that prevention of harassment and abuse is everyone’s responsibility

- Communicate clear and consistent policies and procedures

- Introduce and enforce the legal and moral duty to report for all sport organizations

- Make third party investigation and adjudication mandatory

- Establish pools of trained Sport Welfare, Investigating and Hearings Officers to implement the policies

- Shift the focus to prevention of harassment and abuse

The Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) was developed in 2019 by the CCES with SIRC and in collaboration with national and multi-sport organizations, athletes, coaches, researchers and experts in the areas of child protection and safety in sport. The UCCMS 6.0 underwent a recent update by the SDRCC and is a vital tool for communities and organizations when it comes to implementing safe sport practices. The latest version includes prevention strategies for all levels of Canadian sport organizations and guidelines on how to address maltreatment if it occurs.

UCCMS violations are investigated and sanctioned by the Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner (OSIC). The OSIC is the central hub within Abuse-Free Sport, Canada’s independent system for preventing and addressing maltreatment in sport. The Sport Dispute Resolution Centre of Canada (SDRCC) launched the Abuse-Free Sport program in 2022 after extensive research and a national consultation with more than 75 different organizations. The government of Canada selected the SDRCC to develop and deliver this new safe sport mechanism at the national level in 2021.

Abuse-Free Sport provides access to a wide range of resources, all of it available in English and French, including:

- Canadian Sport Helpline

- Safe Sport Education Accreditation Program

- Legal Aid Program

- Research Grant Program

- Mental Health Services

- Policy Support

You can visit SIRC’s safe sport web hub for more safe sport resources, including policy documents and relevant research. For safe sport education and training, the Coaching Association of Canada offers Safe Sport Training, a free online training module. The Respect Group also offers Respect in Sport Training targeted at coaches and program leaders, as well as parents.

Conclusion

There are several evidence-informed approaches to sport delivery that researchers and sport organizations encourage, and that you can engage with, to promote positive experiences and combat harmful cultures in sport and society. Quality sport, values-based sport and safe sport are 3 common approaches promoted by sport researchers and practitioners to optimizes experiences and outcomes for sport participants. Although they have their differences, each of these approaches recognizes sport as a context for communities and participants to gain valuable benefits. These approaches promote morals and principles that aim to fulfill basic human needs like belonging, safety, and confidence, which encourage healthy development and overall wellbeing for all sport participants. At the end of the day, the goal of each approach is to encourage positive sport experiences that build thriving people and communities.