Highlights

- At its core, the Safe Sport movement is about optimizing the sport experience for all—athletes, coaches, sport administrators, officials, support staff, and others in the sport environment.

- Broader societal changes have influenced the Safe Sport movement:

- Changing approaches to child and youth development

- The #MeToo/Time’s Up movements

- Increased attention to equity, diversity, and inclusion

- Highly publicized cases of athlete maltreatment

- For sport leaders, understanding the process of change (i.e., denial, resistance, exploration, and commitment) can be useful to successfully embedding Safe Sport practices within their sport.

This article addresses the next steps in the Safe Sport journey; specifically, how to move from a focus on prevention of harms to a focus on optimizing the sport experience for athletes and sport leaders alike. This journey involves a cultural change in sport—one that challenges some traditionally accepted assumptions and practices and encourages the adoption of new methods. Building on my work with National Sport Organizations (NSOs), this article has three aims:

- To show that Safe Sport extends beyond the prevention of harms to the optimization of sport experiences;

- To highlight some of the broader societal influences on Safe Sport, which are also affecting other sectors in Canada and abroad;

- To address some of the common concerns and questions about Safe Sport.

Designed to be helpful for sport leaders—administrators, coaches, officials, and support staff—as well as athletes, this article will begin with the defining characteristics of Safe Sport, then move to the broader societal influences on sport, and will conclude by addressing some common questions posed about Safe Sport.

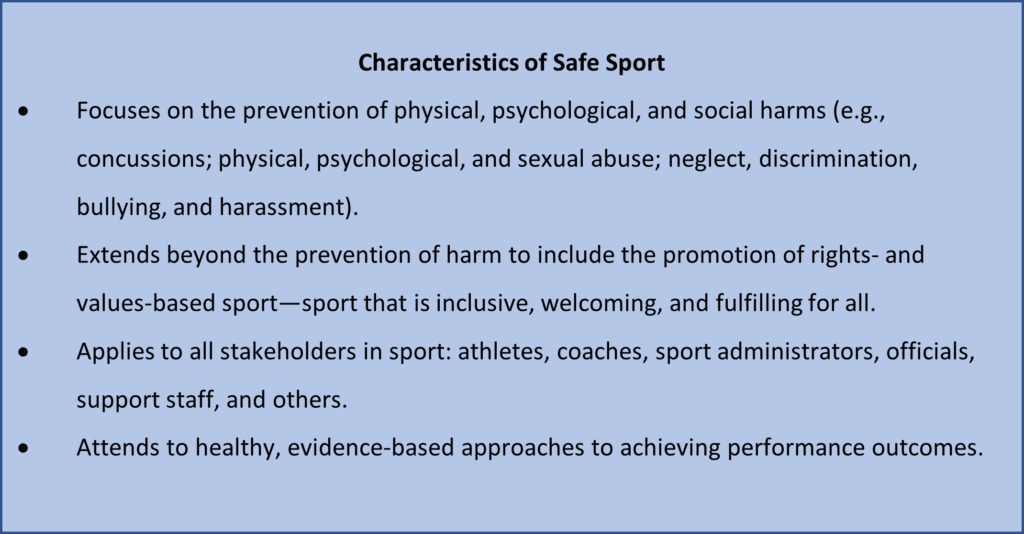

Safe Sport is More than Prevention of Harms

At its core, the Safe Sport movement is about optimizing the sport experience for all—athletes, coaches, sport administrators, officials, support staff, and others in the sport environment. To optimize the experience, stakeholders should have the reasonable expectation that the sport environment will not only be free from all forms of maltreatment (i.e., abuse, neglect, bullying, harassment, and discrimination), but that it will also be accessible, safe, welcoming, and inclusive; will contribute to wellbeing; be enjoyable and respectful of personal goals; and provide a sense of achievement. This is true for athletes and sport leaders, alike.

The Coaching Association of Canada (2020) reflects this perspective in its definition of Safe Sport: “Our collective responsibility is to create, foster and preserve sport environments that ensure positive, healthy and fulfilling experiences for all individuals. A safe sport environment is one in which all sport stakeholders recognize and report acts of maltreatment and prioritize the welfare, safety and rights of every person at all times.” When the priority is optimizing the sport environment, the prevention of maltreatment or harms becomes a natural by-product.

Reflection: When sport is safe, welcoming, inclusive, and fulfilling, and is respectful of individuals’ rights and welfare, prevention of harms occurs naturally.

A question that often arises in discussions about Safe Sport is “what about performance outcomes?” For sport to be a fulfilling experience, individuals, including athletes and sport leaders, must feel a sense of achievement. Athletic results remain important in Safe Sport; the focus, however, is on healthy, safe, and inclusive methods of achieving performance results. More will be said about this later in the article.

A Cultural Shift

In many ways, Safe Sport has stimulated a cultural change. Some previously accepted practices, such as having coaches share hotel rooms with athletes to save costs, is no longer acceptable. Similarly, for decades, practices such as using exercise as punishment were simply an accepted part of sport; but now, we know more about the problems associated with using punishment, and even more importantly, we know that disciplinary strategies are far more effective (Nelsen, 2011). Among others, these changes have required all of us in sport to adapt and learn new strategies and ways of interacting with one another. In some ways, these calls for new ways of doing things are part of the long history of cultural changes in sport to make sport more equitable, inclusive and safe. It was not that long ago that women were permitted to run the marathon or that criminal prosecutions were introduced for violence in sport. Historically, we’ve seen enhanced protection of the health and safety of athletes through the introduction of mandatory protective gear in many sports, changes in rules and eligibility requirements, and return-to-play concussion protocols. Sport has continuously evolved to protect the safety, wellbeing, and rights of participants—and the Safe Sport movement is a key part of this trajectory of cultural change.

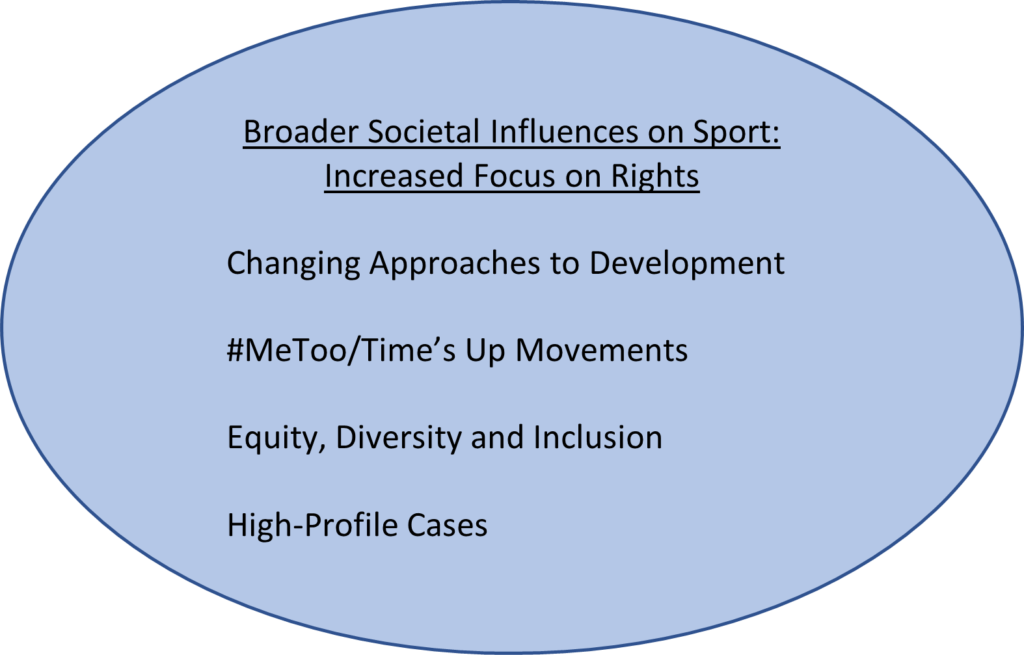

Influences on the Safe Sport Movement: A Focus on Human Rights

The Safe Sport movement has been influenced by broader societal changes, especially the heightened attention to the rights of children and youth, women, and other equity-seeking groups. It is true that norms, standards, and expectations for sport leaders’ conduct have changed. This is also true of others in positions of power and authority in Canadian society, from teachers, doctors, and lawyers to those in business and politics—even parents. And, that’s a good thing! It’s a good thing that teachers no longer physically strike children or that employers can no longer sexually harass employees without consequence. Society expects those in sport to align norms and practices with those in other sectors that involve young people.

1. Changes in Approaches to Child, Youth, and Emerging Adult Development

In Canada, childhood and adolescence are viewed as critical stages of life because experiences during these years influence later health, wellbeing, and developmental outcomes. As a result, both parenting and education have shifted to emphasizing child/youth-centred approaches. These approaches do not mean that the adults in positions of power and authority give up control or hand over decision-making to the younger person. But, it does mean that these adults base their decisions and actions on the rights and developmental needs of the younger person. As an example, developing a sense of competence (i.e., feeling proficient or “good” at something) is very important for those in middle and late childhood years (approximately 7- to 11-years-old) (Erikson, 1968). For a coach, this translates into ensuring children feel good about themselves by encouraging and praising them for their performance of an athletic task, or for their attitudes, effort or sportspersonship. Children who receive little or no encouragement and praise from coaches may struggle to develop this sense of competence, leaving them with less self-confidence, a reluctance to try new things, less enjoyment, and therefore less likelihood of continuing with sport.

For sport leaders, a person-centred approach also extends to athletes over the age of 18 years. The age group of 18- to 24-years-old, historically considered adulthood, is now considered “emerging adulthood” (Arnett, 2000). By virtue of extended periods of education, and delays in ages of financial independence, marriage, and child-bearing, this new age group is considered a key developmental period influenced by adults in positions of power and influence. Importantly, as many high performance athletes are within this age group, coaches retain significant influence on the athlete’s health, and on the development of that athlete in sport and as a person. While the coach maintains a position of power and authority over athletes in this age group, a person- or athlete-centred approach that engages athletes in decisions that affect them would be developmentally appropriate.

2. #MeToo/Time’s Up Movements

The #MeToo and Time’s Up movements have permeated virtually every sector of Canadian society, including business, industry, politics, education, and of course, sport. Although the focus of both movements is sexual harassment and abuse, at their foundation is a push for the right to be physically and psychologically safe. This requires a change in the ways power is used. No longer is it acceptable or tolerable for people in positions of power and authority to use these positions to harass, threaten, exploit or otherwise take advantage of others. These movements have provided clarity about how power should and should not be used and have raised the bar for acceptable behaviours. Safe Sport encompasses the rights for everyone to experience physical and psychological safety in the sport environment, calling for power to be used in positive ways.

3. Increased Attention to Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

Canadian organizations, including those in sport, have been challenged to reflect on advancing equity, diversity, and inclusion. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission and Black Lives Matter, as two examples, have heightened our awareness of historic and persisting systemic oppression and discrimination that translate into the denial of rights. The same can be said of gender and sexually diverse individuals, new Canadians, and Canadians with a disability. Safe Sport, which includes a focus on preventing and addressing discrimination, aims to advance respect of human rights and our practices of inclusion.

4. High-Profile Cases of Athlete Maltreatment

Highly publicized cases of athlete maltreatment, in Canada and internationally, have also increased awareness of the need for Safe Sport. The public eye is on sport with clear expectations to “do better” to prevent and address athlete maltreatment. In the past few years, the sport community has devoted significant time, energy, careful thought, and financial resources to developing measures to address this problem. Some of these changes were stimulated by the support of the former Minister of Science and Sport, Kirsty Duncan, who made the eradication of athlete maltreatment a priority and claimed that “a systemic culture shift is required to eliminate maltreatment, including sexual, emotional, and physical abuse, neglect, harassment, bullying, exploitation and discrimination” (Canadian Heritage, 2019). Since then, initiatives such as the creation of the Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) and the Coaching Association of Canada’s Safe Sport Training have been implemented to advance Safe Sport.

Adapting to Change

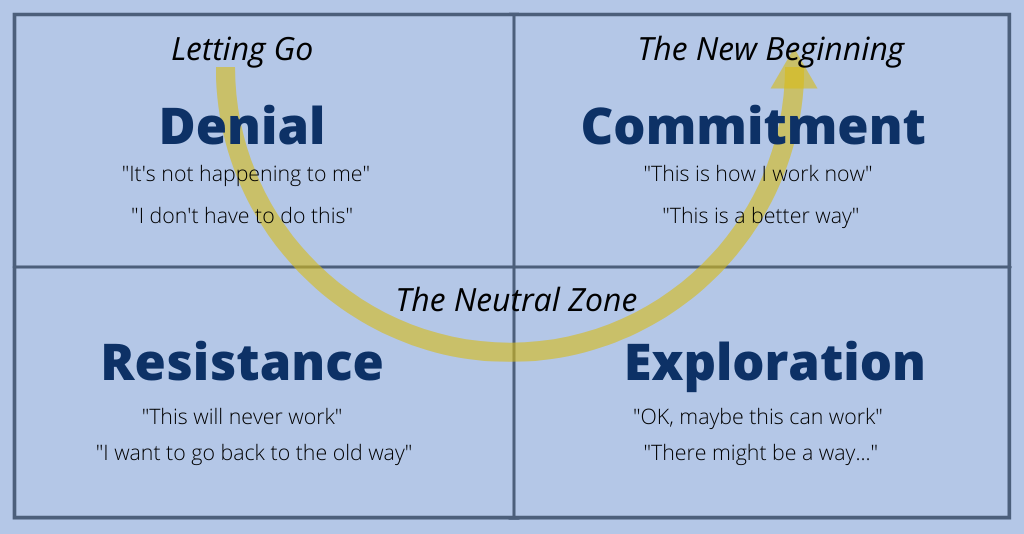

Whenever broad-based changes are introduced in a society, sector, or an organization, a range of responses can be anticipated, including anxiety and uncertainty, resistance, reluctance, tensions, backlash, acceptance and commitment. (We have observed this recently during the pandemic with various and evolving responses to public health standards for physical distancing, mask-wearing and vaccinations.) With respect to Safe Sport, it’s helpful for leaders to understand the process of change and associated emotions to help others better adapt to the Safe Sport journey. Below are the psychological Stages of Change (Scott & Jaffe, 1988) that are common when individuals are confronted with significant calls for change.

These Stages of Change are relevant to Safe Sport. The pursuit of Safe Sport is a journey characterized by challenges to long-held assumptions and practices, new learnings and calls to adapt one’s behaviours. While some individuals are already in the commitment stage and have been using Safe Sport practices all along, for others, denial and resistance may exist.

To help sport stakeholders move through this process of change, it is important to understand and address concerns, questions, doubts, and potential reasons for resistance. The next section will address some of the common questions sport stakeholders have asked about Safe Sport.

Addressing Common Questions about Safe Sport

Why do practices need to change if they have worked in the past to produce podium finishers?

For some individuals, the response to calls for changes to traditionally accepted or “old school” sport practices may arouse reactions of denial like “I don’t have to change.” This may be especially true of those who have produced successful athletes: “My athletes were podium finishers so my practices obviously worked.”

Yes, “old school” methods can work if “working” means putting athletes on the podium—but at what cost? Aggressive, berating, punishing coaches’ practices were at one time accepted as part of tough coaching, but today this conduct may be deemed as emotionally abusive (Stirling & Kerr, 2008). These behaviours are viewed differently now because research evidence shows the detrimental short- and long-term harmful effects of these behaviours on athlete’s mental health and wellbeing (Kerr et al., 2020; Stirling & Kerr, 2013; Vertommen et al., 2016). In addition, these practices run contrary to the huge body of research on how people best learn and grow. Finally, young athletes who experience these behaviours are more likely to leave sport (Battaglia et al., 2021; 2020, 2017), thus harming sport’s reputation, depriving young people of opportunities to grow and develop, and reducing Canada’s talent pool. Getting through the denial phase involves letting go of some “old” practices and assumptions.

Does Safe Sport mean that coaches need to be “soft” on athletes?

Optimal athletic performances (at all levels of sport) require athletes to move out of their comfort zones and sometimes this means the coach needs to encourage the athletes to do so. Safe Sport does not mean that coaches cannot encourage athletes to move outside of their comfort zones. But, what it does do is stimulate reflection on whether the coach takes control and ‘pushes’ the athlete, or leaves responsibility with the athlete by ‘encouraging’ the athlete. Safe Sport also means that practices to encourage athletes to train harder (e.g., do another rep or another skill in spite of fatigue or soreness) are safe, physically and psychologically, and evidence-informed. Coaches can be demanding and firm, and hold high expectations, without engaging in abusive behaviours.

Does Safe Sport mean that coaches cannot develop a close relationship with their athletes?

Safe Sport does not mean that coaches cannot develop a close, trusting relationship with their athletes. In fact, research on achieving optimal athletic performance cites the importance of have a close, trusting coach-athlete relationship (Jowett, 2017). From a Safe Sport perspective, such relationships can and should occur for wellbeing and optimal performance, but that relationship boundaries need to be maintained, and interactions, to the extent possible, should occur in public.

How will Safe Sport practices affect medal counts on the world stage? Safe Sport may work at lower levels of sport but not at the high-performance level.

The most commonly reported behaviours of maltreatment are harsh personal criticisms; statements that are threatening, belittling, or degrading; body shaming; the use of exercise as punishment; and sexist jokes and remarks (Kerr, Willson, & Stirling, 2019). There is no evidence that these behaviours produce optimal athletic performance. However, there is evidence that these practices lead to drop out from sport (Battaglia et al., 2021; 2020, 2017), thus reducing our talent pool. There is also evidence that these practices lead to mental health challenges such as anxiety, depression, and eating disorders among athletes (Kerr et al., 2020; Stirling & Kerr, 2013; Vertommen et al., 2016), none of which assist with sport performance. Finally, these harmful practices run contrary to everything we know about how people best learn and are motivated (Deci & Ryan, 2008). Safe Sport and performance outcomes are not at odds with one another.

Reflection: When do any of us perform at our best—in our relationships, in our jobs, in our parenting? When we feel good about ourselves. When we feel competent, and when we feel supported. The same is true for performance in sport.

Doesn’t Safe Sport open the door for athletes and parents to complain about abuse when athletes are not selected to teams or when they receive less playing time?

Making decisions, sometimes unpopular decisions, such as de-selection, are fundamental to the work of sport leaders. As long as the criteria for making these decisions are transparent and known to those affected in advance, decisions adhere to these criteria, and the decisions are communicated in a respectful manner, those at the receiving end have no grounds for claiming abuse. The Safe Sport approach encourages sport leaders to use their positions of power in respectful ways but does not preclude leaders from making the decisions for which they are responsible.

How can sport leaders apply consequences to athletes without being accused of abuse?

Safe Sport enables sport leaders to apply consequences for inappropriate conduct while encouraging respectful ways of doing it. Outside of sport, in parenting and education for example, the use of positive discipline and natural consequences have replaced the use of punishments for behaviours that don’t meet expectations (Nelsen, 2011). Positive discipline refers to teaching and guiding athletes by letting them know what behaviour is acceptable, helping them understand why behaving in an acceptable manner is important, and articulating how to achieve the acceptable behaviour. For example, a coach may communicate the expectation that a team curfew is in place, that curfews are important because they help to ensure athletes are rested and prepared for the next day’s training/competition, and that to meet curfew they’ll need to leave the appropriate amount of time to return to where the team is staying. Positive discipline is preferred over punishment because it teaches self-control, a sense of responsibility, builds a sense of competence and self-confidence, and maintains the integrity of relationships.

So, what do you do when rules are breached or conduct is unacceptable? Natural consequences are now favoured instead of punishments. Natural consequences are those things that happen in response to behaviour that are imposed by nature, society, or another person. Examples of natural consequences include getting cold hands in the winter when we don’t wear mitts, a child failing a test because they chose not to study, or receiving a speeding ticket when we drive too fast. These natural consequences encourage compliance with normative, expected conduct. In the example above, if the athletes know in advance that missing curfew is associated with not playing in the next day’s game, not being played in the next day’s game is a natural consequence. The benefits of using natural consequences is that decision-making remains with the athlete, they teach self-control and a sense of responsibility, and maintain the integrity of the relationship between athletes and coaches.

Reflection: We often refer to the benefits that young people glean from sport, including skills and competencies that will assist them later in life (e.g., self-responsibility, self-control, decision-making, perseverance). Using evidence-informed practices such as athlete-centred approaches, positive discipline, and natural consequences assist us in teaching life skills.

With all of this attention on athlete maltreatment, how can we avoid creating a culture of fear?

We must remember that far too many Canadian athletes have lived in fear for far too long. There is no shortage of accounts of athletes being afraid to speak up, afraid to have a voice, and not disclosing or reporting their experiences of maltreatment. We must create a safer environment for athletes, and in the process of doing so, we must not create an unsafe environment for other stakeholders. Achieving both will require clear communication and a shared understanding of expected conduct, maintenance of relationship boundaries, and help in adapting to new ways of doing things. This is one reason why training and education are so important. All sport stakeholders need to learn about expected conduct and standards for behaviour and if we adhere to these, we’re far less likely to be the recipient of a complaint. The best thing we can do to prevent a culture of fear is to create physically and psychologically safe environments that are welcoming, inclusive, and rights-based.

Why is the focus of Safe Sport on everyone instead of only those who have behaved inappropriately?

The vast majority of sport leaders are not abusers, but Safe Sport is important for all leaders for several reasons. First, leaders may observe or hear about experiences of maltreatment. By virtue of being in a position of power and authority as leaders, there is a responsibility to care for the wellbeing of young people and each other, and in some circumstances, there is a duty to report abuse to the authorities. It is therefore important to know what behaviours constitute maltreatment, how to intervene as a bystander, and when there is a duty to report. Learning more about Safe Sport also enables us to better support one another in adapting to culture changes. All of us in sport have a collective responsibility to create and ensure safe sport environments.

Next Steps in the Safe Sport Journey

In recent years, the national sport community in Canada has responded to the high-profile cases of athlete abuses with the development of the UCCMS and associated Safe Sport training offered by CAC and others. These are critical steps as members of the sport community need to know which behaviours are prohibited and which practices, even if historically accepted, need to be replaced.

However, the next step in the Safe Sport journey is equally important. The UCCMS stipulates ‘what not to do’ but does not address ‘what to do.’ Coaches have often been heard saying “I get that I can’t do XX anymore, but what do I replace it with?” or “If I can’t use these practices, what do I use instead?” These are legitimate questions and education on evidence-based practices will be particularly important in the coming years to help members of the community comply with Safe Sport expectations, and to maximize sport experiences for athletes and sport leaders alike. These are some of the challenges that lie ahead for the Safe Sport movement.

In summary, Safe Sport serves as a reminder of the potential and promise of sport to contribute in positive and important ways to the overall health, learning, and development of individual participants and the public good. With a focus on the provision of safe, inclusive, welcoming environments that respect individual rights and welfare for all, harms will be prevented, more participants (athletes, coaches, officials, etc.) will remain in sport, and athletic performance will improve. Safe Sport has necessitated changes to traditionally accepted assumptions and practices, particularly with respect to the development of athletic talent. This process of change, which other sectors of society are also experiencing, can cause uncertainty, anxiety, and resistance. The keys to bringing people along this journey are to reinforce the goals and vision of Safe Sport and provide education and support to make the needed changes. By doing so, all stakeholders in sport will benefit. The public expects this of sport!