For community sport organizations, understanding what members value, their suggestions for improvement, and desires for future programming, is essential for long-term success. For the Rocky Point Sailing Association, findings from a membership survey helped inform return to play strategies and engaged members in setting the organization’s vision for 2021.

Integrated physical activity programs for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities not only offer benefits for participants, they can also influence the attitudes and behaviours of others. Learn how the APEX program is impacting support workers, program volunteers, and other members of the University of Windsor community, in the SIRCuit.

In the winter of 2020, the Rocky Point Sailing Association (RPSA) in Port Moody, BC was preparing for the upcoming season. RPSA is primarily run by volunteers and employs ten seasonal full-time staff who deliver long-term athlete development (LTAD) programming to more than 600 participants annually. When the COVID-19 pandemic was announced, summer programs were nearly sold-out and dozens of school field trips were booked for the spring.

RPSA’s Executive Committee immediately established a taskforce to help understand the pandemic restrictions and their implications. Initially, we were optimistic. We thought perhaps by summer the pandemic would pass. When it became clear COVID-19 was here to stay, anxiety set in about RPSA’s future. Ultimately, RPSA’s volunteers and staff developed return to sport policies, safely ran physically distanced programs, and effectively managed finances to ensure the organization’s long-term financial health. For our Executive Committee, it was a humbling experience, albeit a bit of a paradox – although COVID-19 kept our community physically apart, it also brought our community closer together through a shared passion and hope in a mutual future. This blog shares some of our learnings and actions.

Engaging the community

In March we reached out to our membership and asked for help. A volunteer taskforce was created and met weekly virtually. The taskforce engaged the broader sport community and beyond (e.g., BC Sailing, viaSport, other sport organizations, and the City of Port Moody) to learn more about what was going on and what to do. Being a part of a broader sport community and having access to COVID-19-related resources was invaluable. The taskforce engaged coaches and parents to ensure they had a voice in RPSA’s COVID-19 planning. Coaches were keen to be involved and parents overwhelmingly wanted summer programs to run, physically distanced of course. Many parents wrote letters of support which contributed to a successful BC Community Gaming grant application. We also engaged RPSA’s founding members, who are now in their 70s and 80s. In the 1990s, these leaders started RPSA from scratch thanks to a small municipal grant, equipment donations, and a lot of volunteer support. We believed it was important that we check in and learn from their experiences.

Being a part of a broader sport community and having access to COVID-19-related resources was invaluable. The taskforce engaged coaches and parents to ensure they had a voice in RPSA’s COVID-19 planning. Coaches were keen to be involved and parents overwhelmingly wanted summer programs to run, physically distanced of course. Many parents wrote letters of support which contributed to a successful BC Community Gaming grant application. We also engaged RPSA’s founding members, who are now in their 70s and 80s. In the 1990s, these leaders started RPSA from scratch thanks to a small municipal grant, equipment donations, and a lot of volunteer support. We believed it was important that we check in and learn from their experiences.

Developing health & safety policies

Developing and operationalizing COVID-19 health and safety policies seemed like a daunting task. viaSport and BC Sailing’s return to sport guidelines provided a comprehensive and helpful framework. RPSA was fortunate to have some members who are workplace health and safety professionals. They guided us in operationalizing polices. We assigned a Health and Safety Officer to ensure policy compliance and to whom members, participants/parents, and coaches could report any issues or concerns. In addition to adhering to the standard COVID-19 precautions, participants were assigned equipment for the duration of a program, equipment and high-touch points were cleaned after each use, and masks were required on land. The coaches were creative in adapting programs. They fundamentally shifted the way LTAD programs were taught at RPSA while maintaining a safe and quality experience for participants. Games still happened (although socially distanced), and smiles were still had. Lessons that were usually taught on double-handed dinghies (e.g., sailboats for two people) were taught on single-handed boats.

Understanding the financial situation

RPSA has been fortunate to have a series of dedicated Treasurers who diligently managed the finances. Nonetheless, COVID-19 introduced a layer of complexity that no volunteer should bear alone. We had to cancel all regular scheduled programming and issue mass refunds, rethink budgets, apply for emergency funding, and reopen registration for limited capacity adapted programs. The taskforce supported the Treasurer by gaining a collective understanding of COVID-19’s impact on RPSA’s finances. For example, programs were to run at 10% of usual capacity which represented a 79% reduction in revenue. By quantifying and understanding both the short-term and potential long-term impacts, the taskforce was able to make informed decisions on spending and plan for scenarios in 2021.

Succession and legacy planning

Needless to say, mitigating the impacts of COVID-19 was a lot of work. We were conscious of volunteers’ personal and professional lives and the general stress caused by the pandemic. We performed a SWOT analysis and identified succession planning as a “weakness”. As such, we actively recruited new members with diverse backgrounds and experiences who were keen to help RPSA navigate the “new normal” in 2021. We also engaged a coach to survey members and participants/parents from the past two years. We learned what members and participants/parents valued, where RPSA could improve, and what participants/parents would like to see for future programming. The insights were shared in a report which made a series of recommendations and set a planning framework. The report was helpful in engaging volunteers in contributing towards a vision for 2021. More so, COVID-19 accelerated the “digitization” of RPSA. We had record attendance at monthly virtual general meetings, scheduled automatic payments for fixed costs, and all planning documents and funding applications were stored and organized in Microsoft SharePoint. A file sharing platform was essential in facilitating and preserving organizational knowledge.

Final thoughts

Volunteers are vital to the Canadian sport system. RPSA would not have been able to navigate COVID-19 without the help of dedicated volunteers and staff, support from the broader community, and access to sport-related COVID-19 resources from various regional sport organizations. Having a clear understanding of RPSA’s mission, vision, and impact on the community helped to guide the taskforce’s decisions and recruit new members. RPSA’s success this summer has been a morale booster and strengthened our community. Moreover, the pandemic accelerated change and forced RPSA to innovate and ultimately enhance its operations. The incredible amount of work was powered by our belief that community sport is an important part of our social fabric. It gives youth the opportunity to learn a new skill, make new friends, build confidence and develop a passion that will hopefully stay with them as adults. I hope our experiences contribute to the growing body of knowledge of sport in the era of COVID-19.

Giving Tuesday is a global movement for giving and volunteering, harnessing the potential of social media and the generosity of people to bring about real change in their communities. Research on the social responsibility activities of community sport organizations (CSOs) discovered members who are aware of the good things their CSO does beyond their sport programs are more likely to speak positively about the organization to others, and are more likely to stay involved in the future. Check out the SIRCuit for tips to increase the social impact of your organization.

Virtual volunteering can reduce some of the barriers to volunteering with more schedule flexibility, micro assignments requiring shorter time investment, and allowing people to contribute from home. Learn more in the SIRCuit.

Thinking of developing a new program or initiative? Before you start, research suggests completing a “capacity audit” to identify any gaps in available resources. The audit could include human resources (e.g., number of volunteers, level of expertise among executive members), financial resources (e.g., availability and stability of funds), existing relationships (e.g., quality of partnerships), planning (e.g., alignment with strategic plan), and existing infrastructure (e.g., access to facility space, equipment).

Community sport organizations (CSOs) occupy an important place in our communities by providing sport and recreation opportunities for all ages, as well as serving a wider social role within our communities (see, for example, Taking Action: Community Sport Organizations and Social Responsibility by Misener, 2018). Previous research has pointed to the challenges these organizations face, including growing demands for services, competition for resources, and greater accountability to stakeholders and funding partners (Musso et al., 2016; Nichols et al., 2015). These challenges are not unique to CSOs but are perhaps accentuated in Canadian sport context given the reliance on a volunteer workforce, modest budgets, and the relatively informal nature of their organizational structures (Doherty et al., 2014). Perhaps now, more than ever, with unique challenges and uncertainty introduced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, a strategic approach to capacity building may be particularly useful (see recent “Return to Community Sport” commentary). This article introduces a model of capacity building, providing an approach for CSOs to address challenges and leverage strengths in order to achieve program and service delivery goals.

What’s involved in a strategic approach to capacity building?

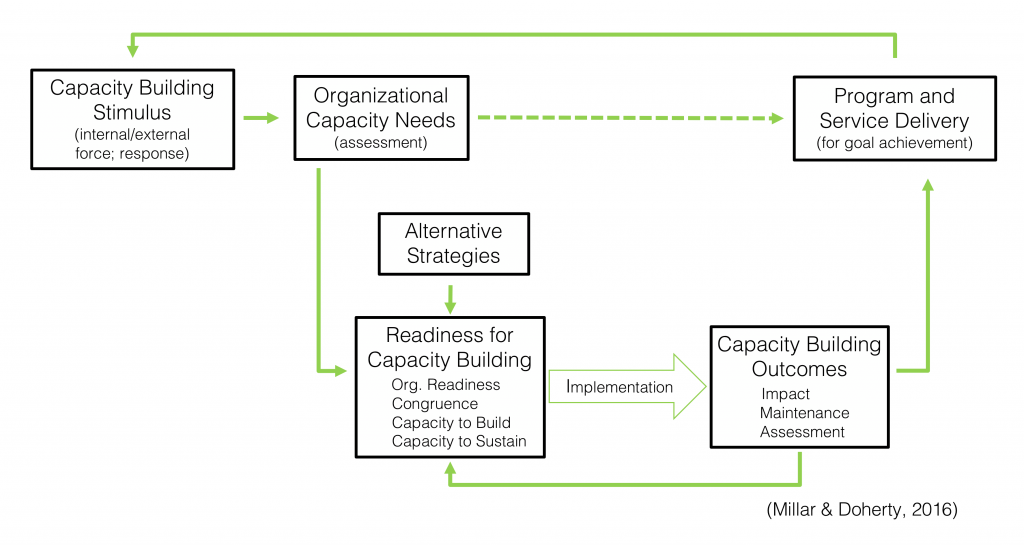

Capacity building refers to developing an organization’s resources (e.g., human, financial, infrastructure, planning, external relationships) and improving its ability to use those resources to successfully respond to new or changing situations (Aref, 2011). Based on learnings from two case studies and 144 cases of capacity building in CSOs, and existing research in this area, we developed, and subsequently examined, a process model that provides a step-by-step roadmap for organizations engaging in capacity building (see figure below; Millar & Doherty, 2016). Within the Canadian sport context, we believe the use of a targeted approach to capacity building that addresses the unique strengths and challenges of individual organizations will be most effective.

Step 1 – Identify the reason for engaging in capacity building

Our findings revealed that successful capacity building begins when a stimulus is placed on an organization. Therefore, in order to begin the capacity building process with a clear vision and a strategic focus, CSOs should pay particular attention to the forces within their internal and external environments. These forces trigger the organization to determine an appropriate response – one that will address the nature of the specific force and that is reasonable for the organization to pursue. Together, the force and associated response represent the stimulus for capacity building. Capacity building in the CSOs involved in our research was most often triggered by decreasing club membership, new programming demands, or conflict with club partners. In response to these forces, CSOs chose a range of strategic responses, such as introducing new programs or initiatives to attract members, targeting recruitment efforts, altering registration fees, and introducing recruitment and training initiatives for volunteers, coaches, and board members. Clearly understanding the stimulus that drives capacity building will ensure CSOs invest their time and energy effectively.

Tip: Organizations do not (and should not) engage in capacity building efforts simply for the sake of doing so – there should be some external or internal force that requires a response from the organization.

Step 2 – Conduct a thorough capacity assessment and identify capacity building objectives

Whether or not an organization responds to an environmental force depends on its capacity to do so. The particular capacity needs associated with a given stimulus will vary depending on the current state of the organization. For instance, a CSO experiencing decreasing membership may choose to respond by introducing a membership development program. The organization would then assess its current capacity to move forward with this initiative, identifying any capacity needs or assets that may hinder or facilitate that action. Capacity needs or assets may be related to the organization’s human resources (e.g., number of volunteers, certified coaches, level of expertise among executive members), financial resources (e.g., available funds, stability of revenue sources), existing relationships (e.g., quality of partnerships), planning (e.g., alignment with strategic plan), or existing infrastructure (e.g., access to facility space, equipment) (Doherty et al., 2014; Hall et al., 2003). If no capacity gaps exist, then the club moves forward with the proposed response (in this case, the membership development program). However, if gaps are present, the extent and nature of those capacity needs become the basis for the organization’s capacity building objectives. This is a critical step in ensuring that the capacity building process will address the specific needs of the organization – if the objectives are not clear and specific, capacity building efforts are likely to lack focus and, ultimately, be unsuccessful.

Step 3 – Select strategies that align with capacity building objectives

It is important for organizations to choose capacity building strategies that align with their specific capacity needs. An organization may identify a number of potential strategies to address its capacity building objectives, whether those strategies are internal (e.g., re-allocating existing funds, recruiting coaches from existing membership) or external (e.g., applying for government funding, recruiting new volunteers, enrolling in workforce training) to the organization.  Our findings revealed that a key difference between the successful and unsuccessful cases of capacity building were the specific strategies chosen by each organization. Successful capacity building efforts often considered new and untried alternatives that were supported by members, aligned with the organization’s priorities, and were inline with what the CSOs had the capacity to pursue. In contrast, unsuccessful efforts often relied on those strategies that were “easiest and cheapest to do” and, as a result, failed to effectively address the identified capacity gaps. Capacity building strategies are only as strong as the planning that precedes their implementation (Cornforth & Mordaunt, 2011).

Our findings revealed that a key difference between the successful and unsuccessful cases of capacity building were the specific strategies chosen by each organization. Successful capacity building efforts often considered new and untried alternatives that were supported by members, aligned with the organization’s priorities, and were inline with what the CSOs had the capacity to pursue. In contrast, unsuccessful efforts often relied on those strategies that were “easiest and cheapest to do” and, as a result, failed to effectively address the identified capacity gaps. Capacity building strategies are only as strong as the planning that precedes their implementation (Cornforth & Mordaunt, 2011).

Step 4 – Consider whether your organization is ready to engage in capacity building

Effective capacity building relies on overall readiness to engage in those efforts. Our research showed that readiness is based on three factors;

- Organizational readiness – the degree to which board members and volunteers are willing, able, and motivated to support capacity building;

- Congruence – the alignment of capacity building objectives and strategies with existing organizational processes, systems, and day-to-day operations; and

- Existing capacity – the availability of existing capacity that can be leveraged to support and sustain capacity building efforts.

We found that the willingness and commitment of individuals within the successful case study was a key factor leading to that success; while animosity, lack of commitment from organizational members, and general disinterest in the capacity building efforts were key factors in the capacity building “failure” witnessed in the unsuccessful case study. Our findings also showed that congruence in the context of capacity building can be understood in two ways – at the micro-level, where day-to-day operations align with the workload involved with capacity building; and at the macro-level, where the club’s objectives, values, and mandates align with the capacity building efforts undertaken.

Our study of 144 cases of capacity building in CSOs across Ontario examined how ready they were for capacity building, and whether that level of readiness had an impact on the outcomes of those efforts (Millar & Doherty, 2020). Three key findings emerged:

CSOs were most ready for capacity building in terms of the alignment of those efforts with existing club objectives, mandates, and values. Clubs are engaging in capacity building efforts that are congruent with their unique organizational contexts.

CSOs were most ready for capacity building in terms of the alignment of those efforts with existing club objectives, mandates, and values. Clubs are engaging in capacity building efforts that are congruent with their unique organizational contexts.

CSOs were ready for capacity building in terms of having willing, committed, and motivated organizational members to drive the efforts forward. Clubs are relying on the willingness and commitment of their members (volunteers and board members) to drive capacity building efforts forward.

CSOs were ready for capacity building in terms of having willing, committed, and motivated organizational members to drive the efforts forward. Clubs are relying on the willingness and commitment of their members (volunteers and board members) to drive capacity building efforts forward.

CSOs were least ready for capacity building in terms of having existing resources and assets that could be used to facilitate those efforts. Existing capacity also had a unique impact on capacity building outcomes, meaning that the resources an organization possesses are particularly critical in ensuring successful capacity building.

CSOs were least ready for capacity building in terms of having existing resources and assets that could be used to facilitate those efforts. Existing capacity also had a unique impact on capacity building outcomes, meaning that the resources an organization possesses are particularly critical in ensuring successful capacity building.

Capacity building efforts should only be undertaken when they align with the organization’s mission and existing operations, and when the organization can rely on existing resources to support those efforts. Any incongruence or overstretching of organizational resources will likely result in unsuccessful attempts at building capacity or will leave the organization in a less desirable position in the end. Our results showed that the more ready an organization is to engage in capacity building (across all three factors), the more likely they are to achieve their desired capacity building outcomes. In other words, organizations with willing and motivated people, who embark on capacity building initiatives that fit with how the organization operates, and who have resources that they can lean on, are more likely to be successful in their efforts to build capacity and to successfully address the needs of their organization.

Step 5 – Evaluate the short and long-term outcomes of capacity building

Successful capacity building results in both immediate and long-term changes to an organization’s capacity that ultimately contribute to program and service delivery. Whether an organization experiences the desired short and long-term outcomes depends on whether the above steps are followed in a strategic manner. In addition to assessing the impact of capacity building efforts, the attainment of capacity building goals, and addressing the initial environmental force, evaluation of capacity building outcomes is also likely to uncover additional capacity needs and may trigger a reassessment of the organization’s readiness to engage in the capacity building efforts, as depicted by the feedback loop in Figure A (above).

Capacity building during times of change

This articles summarizes our research findings to provide a step-by-step process for CSOs as they engage in capacity building, which may be particularly timely as sport organizations across the country navigate the new sport realities that we are facing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. As sport resumes across the country, and with the risk of future lockdowns, organizations will be facing new challenges and pressures from their environment that require capacity building in one way or another. The approach and insights outlined here provide a framework for organizations as they work to balance, address, and prioritize capacity building efforts, and to determine whether they are ready to engage in those efforts prior to doing so.

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Virtual volunteering is a novel way to engage volunteers during persisting COVID-19 restrictions, but it doesn’t need to stop post-pandemic. Online opportunities can help sport organizations build their pool of volunteers, attract volunteers with diverse skill sets, and become a more flexible and inclusive organization.

As community sport clubs begin their return to play phases, the short and long-term impacts of COVID-19 – on the field and in the office – are unmistakable. Physical distancing measures and stay-at-home protocols have illuminated how technology can keep people connected and involved in their local communities. These new ways of working provide an opportunity for community sport clubs to tap into existing and new volunteers in innovative ways. This article will discuss the concept of virtual volunteering and its benefits. Suggestions are provided below for incorporating virtual volunteering into community sport now and as an ongoing practice to increase capacity and engagement.

What is virtual volunteering?

Virtual volunteering simply refers to volunteer tasks “…done online, via computers, tablets or smartphones, usually off-site from the non-profit organization being supported” (Volunteer Canada, 2019). This form of volunteering is also known as online volunteering, digital volunteering, and e-service. Virtual volunteering is by no means a new concept, and has been around since the start of the internet itself (Cravens & Ellis, 2014). In many cases, on-site and virtual volunteers are the same people, but virtual volunteering can also be used as a strategy to engage people who would otherwise be unlikely or unable to volunteer.

The sport sector is a vibrant context for volunteering in Canada, accounting for almost one quarter of all volunteers (Volunteer Canada, 2015). While many volunteer positions within the sector are considered “on-site” roles such as coaches, officials, and event hosts, sport clubs also rely on volunteers for administration and management support behind the scenes. During the global pandemic, clubs are being required to re-imagine how sport is delivered and how to best support athletes during this time. Many clubs are struggling with new or increased demands requiring technical, administrative, communication and advocacy expertise. Given the uncertainty remaining for the various phases of return-to-sport plans in many sports, it may be helpful to consider how existing and new volunteers can contribute to addressing immediate club needs, and support long-term engagement.

The benefits of virtual volunteering

In a time when so much in our life has changed and feels uncertain, contributing to your community from your home and helping others is important for mental health and overall wellbeing (Lu et.al, 2019). Times of crises can strengthen people’s pro-social behaviours such as volunteering. Some volunteer agencies such as Volunteer British Columbia have noticed an increase in the number of people wanting to volunteer during the pandemic, which the organization attributes to an increase in people’s amount of free time (Zillich, 2020). In particular, volunteering in community sport can build a sense of community and connection between like-minded individuals (Dickson, Hallman & Phelps, 2017). Typical forms of sport volunteering can generate the perception that volunteer involvement requires face-to-face interaction and set schedules. However, virtual contributions to community sport organizations can benefit volunteers by allowing for more schedule flexibility and completion of tasks from home.

Virtual volunteering also reduces some barriers to volunteer involvement such as geographic location, physical ability constraints, or inflexible work hours (Volunteer Canada, 2019). For example, 64% of Canadians ages 75 and older expressed that physical ability impaired their ability to participate in traditional volunteering activities (Volunteer Canada, 2015). Virtual volunteering can be an inclusive way to engage busy professionals, older adults with experience in sport clubs, or others with varying physical abilities in the sport community, and foster connections to sport. In return, virtual volunteers can enhance the capacity and resources of the club through contributing their skills and time in a variety of different roles.

Pivoting to Virtual Volunteering

For sport organizations seeking ways to adapt to new circumstances, virtual volunteering could provide a means to gain much needed assistance in advancing club operations. Like other volunteer strategies, success depends on having a clear purpose and strong support for the program (Bezmalinovic Dhebar & Stokes, 2008). Sport organizations should start by conducting a needs analysis to determine where help is required and where virtual volunteer investments could best be focused. Remember that these individuals are part of your overall volunteer team and volunteer management policies and procedures should be applied consistently without distinguishing between virtual and on-site volunteers. Established practices should be applied relating to screening, interviewing, training, and orientation (see Cravens & Ellis, 2014).

Virtual volunteers can be identified through a call to current volunteers and broader membership outlining the opportunities, or by posting virtual volunteer opportunities through your local volunteer agency or on other sites like charityvillage.com and SIRC.ca. In these posts, be clear about the time commitment and any specific skills and technology required for virtual volunteers. As with all volunteers, organizational support is crucial and has benefits for both the volunteer (e.g. decreased stress, increased commitment) and the organization (e.g. reduced turnover, enhanced productivity levels) (Eisenbeger et al., 2011). In order to ensure volunteers feel supported, volunteer orientation is key. Orienting volunteers to the organization, its policies, platforms and training them on any specifics related to their position will help volunteers feel comfortable and competent from the get go. Be transparent as to whether or not it is feasible or not for your organization to provide financial compensation for software or subscriptions to secure virtual platforms that they need to complete certain project or tasks prior to the volunteer agreeing to take on the role. In addition, it may be helpful to decide on and communicate a record system to ensure organization has a consolidated place to store related documents to help virtual volunteers and your organization stay organized.

Ways to Engage Virtual Volunteers

Volunteers can contribute virtually in a variety of roles while social distancing measures are still in place and may continue within these roles as restrictions ease. Such roles could include social media specialist, digital marketing coordinator, administrative assistant, scheduler, video analyst, web designer, community outreach coordinator, online mentor, inclusion education. Volunteer roles assigned in the short-term may help to minimize organizational costs; however virtual volunteering programs designed from a perspective of strategic growth can help achieve program scale (Bezmalinovic Dhebar & Stokes, 2008). As pandemic restrictions continue to lift, consider the potential for virtual volunteering roles to contribute to ongoing minimization or recuperation of funds, as well as opportunities for virtual volunteers to increase capacity and augment organizational growth.

The list below offers 12 ways to engage virtual volunteers in your sport organizations during physical distancing:

1. Implementing return to sport plans

Create a return to sport committee to help customize and implement plans and policies that respect guidance from public health departments and sport governing bodies. Volunteers can help to refine contingency plans for training and competition to their specific local context, while ensuring all plans support a safe and quality experience for members. Volunteers can monitor the communications from relevant sport governing bodies for direction in this process to ensure the club is complying with guidelines and decision making.

2. Tap into new funding streams

Engage a volunteer with expertise in fundraising, sponsorship and/or grant writing to apply for relevant COVID-19 government subsidies, seek new funding opportunities, or develop a strategy to diversify the organization’s funding.

3. Coordinate communications for all return to play related inquiries

While much of the future of sport remains unknown, club members need to feel supported with clear communication related to the future of their sport club and its programs. Designate a group of volunteers to create a webpage and contact line for any return to sport related inquiries to ensure answers are consistent and members feel heard.

4. Support athlete training and skill development

Support current or new coaches in hosting online strength and conditioning or sport skill development sessions for their athletes. Volunteers could facilitate opportunities for coaches to share ideas, curate credible resources, create weekly fitness challenges to support activities, or coordinate an online session with a certified professional for multiple teams. Check out an example from the Oakville Soccer club’s program here.

5. Deliver educational content for members

Tap into expertise amongst your membership or the broader community to deliver educational seminars for your athletes, parents, coaches and others. Topics could include mental health, conflict resolution, bullying prevention, concussion awareness, nutrition or inclusion (consider what is most relevant to your members or club objectives!), with volunteers delivering content based on expertise, and coordinating the sessions. Alternatively, recruit volunteers to identify credible content to share with members, such as TED Talks.

6. Expand the credentials of your volunteers by encouraging participation in an online certification program

Encourage volunteers to engage in online education or certification programs specific to their role. For example, encourage coaches to complete the NCCP Multi-Sport Training Modules or the Coaching Association of Canada’s new Safe Sport Training. Other national sport organizations also provide a range of training and professional development opportunities that can be explored and shared among volunteers such as the Keeping Girls in Sport module and Sport for Life course offerings.

7. Update the club website

A volunteer with website development experience can assess the functionality, accessibility and content of the sport organization’s website and make improvements. The website should be made accessible for persons with disabilities, and new features can be added such as closed-captioned videos. The site should accurately share the latest news on return to sport plans.

8. Build a social media campaign to reinforce club values or follow a specific initiative

Social media campaigns can be developed by volunteers for present or future use to enhance the club’s communication efforts related to specific initiatives or values. Other campaigns could recognize the efforts of current volunteers and promote opportunities for others to get involved. To learn more about how to enhance your organization’s reputation via communications check out Building a pandemic communications strategy must start with this one-word question.

9. Develop an athlete mentorship program

Senior athletes can volunteer as mentors for younger athletes and check in regularly to help them with goal setting, motivation for training at home, and overall wellbeing. Experienced athletes can be introduced to volunteerism in sport in new ways and fuel their interest in coaching and other youth development pursuits.

10. Develop a regular social calendar for your sport club

Assign volunteers to a social committee to create opportunities for members and other volunteers to connect socially, even if they’re not yet on the field or in the pool. Online socials could include activities such as sport trivia nights, bingo, fun skill or activity challenges, cooking bake offs, and more!

11. Engage in the concept of micro- volunteering

Micro-volunteering is another fantastic option to keep volunteers engaged, but not overwhelm them. Some people may be more likely to volunteer their time in short and convenient, bite-sized chunks (i.e. 30 minutes or less). Micro-volunteering offers volunteers a series of easy tasks that can be done anytime, from their own homes, on their own terms. The concept isn’t new; it has historically been done mostly in the UK. Check out the UK-based Help from Home website for ideas and opportunities and download their exceptional free guide. Sport related micro-volunteering examples could include micro-consulting initiatives in the form of posing a question or generating a poll for your social media audience to garner feedback, creative input and ideas on things like club logo, creative artwork or marketing ideas.

12. Partner with other causes and organizations to give back to the community

COVID-19 has impacted many of society’s most vulnerable communities. Volunteers could reach out to local non-profit organizations outside of sport that might need support at this time and coordinate efforts to help among the club membership. Some clubs, such as the TriMuskoka Triathlon Club, have already contributed to hospitals and foodbanks to provide volunteer support and resources during this time of need. Research has shown that members are paying attention to and support their club’s efforts to engage in socially responsible initiatives (Misener, Morrison, Shier, & Babiak, 2020). Club members care deeply about the wider community and clubs who engage in social action may benefit through member loyalty and positive word of mouth.

Retaining virtual volunteers post-pandemic

As public health measures are relaxed and sport clubs begin to offer on-site programming again, virtual volunteers can continue to represent an important lifeblood of a club’s operations. Many of the roles listed above will remain relevant and can evolve into ongoing volunteer roles. Thinking of volunteers beyond the arena or board room can help clubs remain resilient in times of change, but also promote diversity and innovation within the volunteer force.

After orientation, be sure to consistently check in on virtual volunteers. Research shows that after 6 months of taking on a role, perception of organizational support changes and volunteers slowly can feel less appreciated if the organization becomes less attentive to the needs and concerns of volunteers (Eisenberger et. al, 2011). Aim for the latter by recognizing your virtual volunteers and creating opportunities for meaningful contributions and connections.

Under normal circumstances, the commonly cited rule of thumb for remote teams/workers is that the leader may need to communicate, in an intentional way, twice as much as they would were the team situated together in an office space. But these are not normal circumstances. Communication practices with staff should consider current working from home realities such as shared workspaces, homeschooling duties, stress and anxiety, dodgy internet connections, and more.