Power Balance: The black box of the Canadian sport system

April 24, 2024

Within the Canadian sport system lies a black box of power imbalance, a black box the Future of Sport in Canada Commission will need the key to address. Our research offers insights into:

- cost benefits and savings to a power balanced sport model;

- how to build power balance into a system through independence, transparency, and accountability measures;

- key learnings on how power balance can be scaled to any purpose or size.

The costs of power imbalance

Though often well intentioned, power imbalanced structures and hierarchies allow individuals and groups to abuse their power. Power imbalance is often sought and preserved as a misguided means to stability, security, and control. However, the lack of independence can also lead to a lack of transparency, and concrete accountability processes resulting in a recursive cycle of abuse and corruption, which is well documented in academic, media, and government reports (AthletesCAN, CBC, Globe, McLaren, Cromwell, Dubin). Macintosh, Kerwin and Doherty (2023) point to ‘too much of a good thing’ leading us to privilege winning over all else with deleterious effects. Academics (Gurgis & Kerr, 2021) have long highlighted the destructive influence and perpetuation of hierarchical, colonial, capitalistic, and imperialistic principles on sport in Canada leading to inequity, corruption, and human, social, and environmental harms not to mention the financial costs associated (medical, legal, political, remedial) (Walinga, 2022 for a review).

The benefits of power balance

When power is balanced, shared, and distributed, sport participants experience the psychological safety necessary for belonging, trust, contribution, and collaborative learning. When individuals feel safe to be and contribute, they are more likely to inspire learning in others and are more willing to take the risks required to learn themselves. The group is thus more equipped to challenge one another, the program, and the system as a whole in the spirit of operating as a learning organization. And of course, learning is central to sport.

Our study of the 1992 Canadian Rowing team illustrated how a partnership model achieves excellence and avoids psychological, physical, reputational, relational, and cultural costs along with associated financial costs of a hierarchical model (Figures 1 and 2).

Power balance through independence, transparency and accountability

We need only look to best practice in sport itself as a scalable model for sport organizations and systems no matter how small or large. In our studies of effective sport teams, we found that independence and transparency lead to a culture of respect, equity, health, and excellence. Independence was built into the system by separating the evaluation and education (coach) from qualification functions (independent director applying ‘gold medal standards’). Today, the IOC and National Olympic Committees determine the qualification standards for the Olympics and the International Federations research and provide ‘gold medal standards’ relevant to each sport.

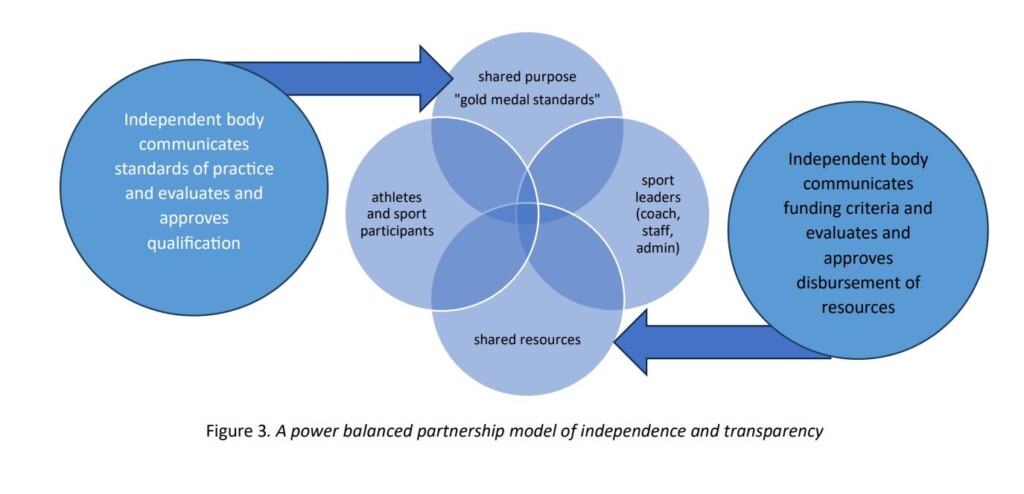

Likewise, transparency creates a partnership model of shared goals and collaborative process (Figure 3) rather than a power imbalanced model of authoritarian control and compliance. Ensuring that evaluation criteria are comprehensive, public, objective, and grounded within standards of practice, the coach would post performance targets, criteria, and measures early and often and would post athlete performance outcomes daily and publicly resulting in empowered athletes and accountability for all.

Scaling the sport model to the sport system

The partnership model of power balance ‘resources’ rather than ‘rewards’ sport organizations.

Currently, Own the Podium (OTP) educates and evaluates national sport organizations, much like a coach; however, OTP also influences qualification for and nature of funding and resources for national sport organizations, much like a selection committee. OTP is responsible for making targeted high performance funding recommendations to funders (Government of Canada, the Canadian Olympic Committee, and the Canadian Paralympic Committee). A solution would be to place OTP as the ‘coach’, providing education, evaluation, and sport science research and resources, leaving an independent body to determine qualification for and nature of sport funding.

Certainly, evaluation and assessment are part of the coach’s role. It is ‘selection’ that can threaten power balance in the sport environment. OTP could inform empirical criteria for funding and standards of practice and the independent funding body could then enhance transparency by making these standards public. Access to and clarity of policies and standards creates a foundation of understanding, trust, and certainty that allows all in the sport system to focus on performing to standards.

It is possible to re-engineer organizations and systems to be impervious to power abuse through the addition of comprehensive accountability frameworks in much the same way that athletes and coaches are expected to demonstrate evidence of performance standards through regular monitoring, testing and competition. All boards should employ accountability frameworks to monitor organizational performance and require verifiable evidence of policy implementation and achievement of standards of practice as criteria for budget approval. Sport Canada could strengthen their governance role and provide greater oversight by enhancing the Canadian Sport Governance Code and report card to ensure that sport boards are providing verifiable evidence of their governance practice.

The gold standard of sport leadership

A power balanced model reflects the gold standard of sport leadership and encapsulates all of the criteria of sport excellence. Like the educational and political spheres, rather than a ‘watching’ culture of surveillance, sport would benefit from embodying a ‘showing’ culture of independence, transparency, and accountability by our sport coaches, staff, and administrators in the same way we expect of our athletes.

Webinars:

Building Quality Sport in Canada

Building Cultural Integrity Across Canadian Sport

Aligning Governance Practices with Cultural Values

Partners: Boxing Canada, Royal Roads University, COPSIN, The Culture Collaborative

About the Author(s)

Dr. Jennifer Walinga has been an educator for 30 years, and a former member of Canada’s Commonwealth, World and Olympic gold medal rowing teams (1983 to 1992). She draws on her personal, professional, and educational experiences when facilitating problem solving and leadership processes in organizations; and blends organizational, educational, and sport theories in designing communication, change and performance interventions in organizations. She is an award-winning researcher focusing all of her projects on the central theme of optimal human performance. Her research interests include organizational communication, team dynamics, creative insight, social innovation, workplace health, sport education and high performance. She is currently working on culture building projects in the spheres of sport, women in leadership, and workplace health.

References

Padilla, A., Hogan, R. & Kaiser, R.B. (2007). The Toxic Triangle: Destructive Leaders, Susceptible Followers and Conducive Environments. The Leadership Quarterly, 18, 176-194.

Roberts, V., Sojo, V. & Grant, F. (2020). Organisational factors and non-accidental violence in sport: A systematic review, Sport Management Review, 23(1), 8-27.

Thoroughgood, C. N., & Padilla, A. (2013). Destructive leadership and the Penn State scandal: A toxic triangle perspective. Industrial and Organizational Psychology: Perspectives on Science and Practice, 6(2), 144–149.

Van Tuyl, R., Walinga, J. & Mandap, C. (in press). Safe to Be, Contribute, Learn, Challenge, and Transform: Fostering a Psychologically Safe and High-Performance Sport Environment. International Journal of Sport and Society.

Walinga, J. (2022). Insights Into and From High-Performance Athlete Experiences of the Safe Sport Complaint Process: A Knowledge synthesis of the experience of high-performance athletes with the Safe Sport complaint process in Canada and beyond. SDRCC Research Symposium, University of Toronto, September 2022. Unpublished report.

Walinga, J., Obee, P., Cunningham, B.J., & Cyr, D. (2021). The Role of Leadership and Team Culture in Enhancing Sport Performance Outcomes. The International Journal of Sport and Society, 12(2), 81-104.

Watcham-Roy, N. (2022). Psychological Safety in High Performance Sport. [Masters Thesis, Royal Roads University]. Royal Roads University Research. Repository: https://viurrspace.ca/bitstream/handle/10613/25708/WatchamRoy_royalroads_1313O_10816.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

The information presented in SIRC blogs and SIRCuit articles is accurate and reliable as of the date of publication. Developments that occur after the date of publication may impact the current accuracy of the information presented in a previously published blog or article.