Highlights

- High performance coaches and administrators are key stewards of a shift to safer sport

- In our research, coaches and administrators identified 6 challenges to culture change in high performance sport:

- Sport is inherently unsafe

- Turbulent, unstable sport environment

- Lack of system alignment

- Different interpretations of safe sport

- General hesitation and avoidance

- Financial and human resource capacity constraints

- We outline strategies to address these challenges and shift toward safer sport cultures for all sport participants

The calls for culture change across sports in Canada are persistent and louder than ever. Through our program of systematic research, we have listened to and shared high performance athletes’ perspectives about what appear to be accepted (or at least tolerated) unsafe behaviours and practices in sport. Tolerance of unsafe behaviours and practices reflects a “how things are done around here” attitude that stands in the way of culture change (MacIntosh & Doherty, 2005). Effectively pushing sport culture forward must continue to be informed by an evidence-based understanding of the context of change that is needed.

Culture can be shifted over time, by refocusing and entrenching new and different behaviours and practices, and the more positive underlying values they represent (Alvesson & Sveningsson, 2016). In a recent SIRC blog, Jennifer Walinga outlined some mechanics of cultural change that rely on an “audit [of] the culture by peeling back or drilling down through the layers of values and beliefs in order to expose, and then challenge and change, some of the governing assumptions within sport.” Such an audit must include consideration of high performance coaches’ and administrators’ perspectives given their direct involvement in shaping and reinforcing high performance sport culture, and ultimately shifting that culture toward safer sport.

In this article, we share findings of our recent research that focuses on the voices of coaches and administrators regarding safe and unsafe aspects of high performance sport culture in Canada. First, we describe the challenges that high performance coaches and administrators view as opposing culture change in sport. Next, we provide evidence-informed strategies to address those challenges. Building on our research examining high performance athletes’ perspectives of safe and unsafe sport environments, these findings add an important layer to our understanding of high performance sport culture and athlete safety.

Our study: Coach and administrator perspectives

Coaches and administrators are key stewards of a move toward safer sport. They are entrusted with the responsible management and administration of a safe sporting environment through the development, implementation and reinforcement of policy and behavioural practice in their organizations and on their teams. High performance athletes have drawn attention to the critical role of these leaders for ensuring a positive sport space.

As stewards of high performance sport culture, and thus culture change, these leaders have direct experience and insight into the challenges associated with the calls for a new direction. To tap into their experiences and insights, we interviewed 27 coaches and administrators (referred to collectively as “sport leaders” in this article) from 23 high performance sport organizations, primarily national sport organizations (NSOs). We asked them about their perceptions of unsafe and safe sport practices, what can be done to shift to a safer sport culture, and the challenges of doing so.

The challenges of moving to a safer sport culture

The coaches and administrators we interviewed shared what they perceive to be unsafe behaviours and practices in the high performance sport setting, including:

- A focus on outcomes that prioritizes “medals at all costs” and a related hierarchy of funding

- A coach-centered system that enables the abuse of power imbalances and tolerates domination

- A hostile, fear-based environment for all high performance stakeholders

- Ambiguity and uncertainty about what continues to be a weak reporting process for athletes, coaches and administrators who experience maltreatment

They also shared that, in their view, safe sport is characterized by:

- Open communication

- Diverse representation

- Ancillary support for athletes

- Formalization of safe sport policies and terms of reference

- Third-party investigative processes

- Stakeholder engagement in mandatory, as well as voluntary, education and training about safe sport

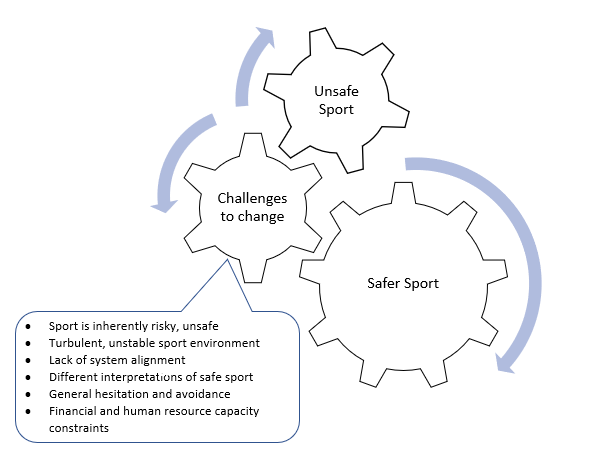

We present our findings as a process of shifting from unsafe to safer sport (see Figure 1) with a focus on the perceived challenges of this shift. The sport leaders we interviewed highlighted several challenges to the process of successfully shifting to a safer sport environment, defined as an environment that is inclusive, supportive, trusting, and enables optimal performance by all stakeholders. We share those findings here, along with supporting quotations.

Challenge #1: Sport is inherently risky, unsafe

Coaches and administrators noted the challenge of creating a completely safe environment, despite best efforts, as sport itself is inherently unsafe. For example, one sport leader described the need to focus on making sport “safer” rather than “safe” while complying with safe sport policies and requirements: “But even once we deal with all of that, it still doesn’t mean that safe is actually possible. You know, there’s inherent risk in sport and in life, so it really is about safer.”

The sport leaders commented on the importance of acknowledging that sport has inherently unsafe features within competition and training. Shifting to a safer sport context requires reflection on what the risk involved in competitive physical activity means for athlete safety. There are undoubtedly gray areas to navigate. For example, to prepare athletes for risky situations in competition, coaches may need to simulate risky situations in training (as safely as possible) so that the athletes can learn how to navigate the situation while mitigating the risk. This is often the combat sports, as described by this sport leader:

“The coaches are in the corner barking out orders because they see something that’s going to take place because they’re experienced… So, in order to prepare athletes for the competition, at that level that they’re participating in, you need to simulate the exact same environment that is going to occur… So, if you are saying, ‘if you please, would you stop doing that behaviour because I think it’s not good for you.’ Or you can say, ‘Hey, do it now. And do it real fast.’”

Challenge #2: Turbulent, unstable sport environment

The sport leaders described the difficulty of moving to a safer sport culture when the current environment continues to be so turbulent and unstable, a place where individuals are afraid to act. “I think that if we found a way for people to not operate in this fear space and in this very threatened space, then we would implement safe sport practices that aren’t just like a show,” said one of the leaders we interviewed. “I feel like right now a lot of people feel incredibly threatened in their roles and incredibly afraid to make a mistake, and therefore are very cautious in terms of how they actually engage in true, safe sport,” the leader added.

The leaders also talked about feeling left behind amid the instability of calls for change and reform efforts and having difficulty sorting through the new dialogue and information. They described feeling reactive and unprotected, rather than supported, when trying to do the “right thing.” According to one leader:

“I think right now, everyone’s kind of just in this reactive zone. [And because of that] you have to rely on, you know, your association to back you if you’re doing the right thing, and I don’t find, I think a lot of times, the associations don’t do that. They don’t really back the process, you know.”

Clearly, sport organizations in Canada are facing new information, new claims of maltreatment, and updated guidelines that may leave them spinning about what to do and how to do it.

Challenge #3: Lack of system alignment

A disjointed sport system was identified as another challenge to moving towards a safer sport culture. The leaders described a disconnect between sport organizations at the community, provincial and territorial, and national levels. This disconnect may be heightened with safe sport efforts. For example, in some sports, national team athletes train independently with local clubs and come together for national team training camps or competitions a limited number of times per year. While national team staff can control the safety of the environment and compliance with safe sport policies during team events, they have little control over the daily training environment in each athlete’s club. As one leader described:

“We have a very decentralized system. We come together only a handful times a year… the majority of time, we’re not centralized. So, [the athletes are] all training at their own clubs. And so, it’s really hard for me to say, okay, like, I’ve got all of my policies and all of my things set in order. But are they actually making an impact?”

Another leader confirmed: “We don’t have necessarily a way of knowing [what is happening at the club level].”

Relatedly, the leaders described being faced with the challenge of navigating different systems and requirements for safe sport across jurisdictions within the same sport. “Technically only our national league and our national team athletes… would fall under our jurisdiction. But… if something happens at the grassroots level or the province, it’s still going to reflect back on our organization,” explained one leader. The leader continued, “We are working to try and align and have some templates available so that our provincial organizations can take the same policies as us, but we don’t really have a way to mandate it. So, it’s still optional.”

There is recognition that for policies to have any effect, there needs to be understanding of where and how they apply and who has jurisdiction over what practices. Navigating jurisdictional boundaries within sport is a mountain to climb for high performance sport leaders.

The leaders acknowledged that one size doesn’t fit all, but if common language and rules are not in place and consistently reinforced within a sport across contexts, then movement forward is stalled. In the words of one leader:

“It’s between lawyers. And the problem with so much of this is that the people at the NSO level that we are dealing with are not lawyers. And they are trying to get a one size fits all for every facet of our sport. But the problem with our sport is that we have clubs, we’ve got universities, we’ve got high schools, and every single one has different rules and obligations.”

Issues with system alignment add complexity to safe sport efforts and leave administrators confused about next steps.

Challenge #4: Different interpretations of safe sport

According to the leaders we interviewed, one of the greatest challenges to a safer sport culture is how different stakeholders interpret what is considered acceptable and unacceptable language, behaviour and practices in high performance sport. As one leader put it, “The issue is complex because there’s an issue around what is the definition of maltreatment or abuse in sport? There are different interpretations of what that means.” For example, one leader described how coaches who come from other countries to work in Canadian high performance programs may have different views about what is considered acceptable or not.

The leaders also described how they are tasked with distinguishing interpretations of safe sport and maltreatment. In the words of one leader, “It’s ferreting out what’s truly maltreatment and what’s perceived as maltreatment but are not truly maltreatment.” Overall, the leaders highlighted their struggle to define common understandings of complex concepts related to safe sport and maltreatment. As a result, the leaders described feeling unsure of how to move forward with safe sport measures like reporting and sanctioning.

Challenge #5: General hesitation and avoidance

The sport leaders we spoke with uniformly identified the need to move toward a safer sport culture, but simultaneously acknowledged a general hesitation in sport to adopt responsibility for the actions needed for change. They also described how such hesitation stands in the way of producing change: “The organization, or the team, or the group, they need to feel like there’s a need for change, right? It’s… you can’t impose change on somebody that, you know, has dug their heels in.”

According to the leaders, people who are resistant to change often feel that safe sport is not their problem to address. “There’s this whole ‘this isn’t my problem’ tension,” explained one leader. In this vein, the leaders described how people who resist change rationalize their decisions with statements like: “I don’t want to have to deal with this. I just want to do my thing. Leave me alone,” and “You’re going overboard.”

Linking back to the turbulent, unstable environment described in Challenge #2, another reason why some people who work in sport may be hesitant to act is the perceived risk of backlash. As one leader stated:

“I want to create a safe sport environment for coaches and athletes and staff. But… how do I do that without getting blamed for certain things that I can’t control? So, for us it’s like trying to minimize the backlash while promoting a safe sport environment.”

Challenge #6: Financial and human resource capacity constraints

Finally, the leaders highlighted how financial and human resource capacity constrained their ability to develop and implement educational, policy, and reporting practices related to safe sport. One leader summed up the issue as a matter of the organization’s survival:

“I was the, not the single employee, but we were pretty small. And we were focused on survival and keeping the lights on. And we just couldn’t do all of the things I probably knew what we needed to be doing.”

The leaders also focused on the role of staff and leadership in achieving safe sport requirements and making safe sport a priority. According to one leader:

“If we really say, you know, the most important thing is that people are safe, then the most important person in the organization [should be] responsible for safety and that [should] be their primary job. And the reality is that there’s very few organizations in which that’s true.”

Another leader commented on the challenge of compliance for organizations that rely heavily on volunteers to deliver their programming:

“Trying to get volunteers to complete some of the training and education is like pulling teeth. So having them, having volunteers trying to get other volunteers trying to comply with this stuff is going to be extremely difficult.”

Others focused on the financial challenges. For example, one leader expressed a need for funding to be aligned how safe sport is intended to be prioritized in the broader landscape of the sport system:

“I think there really needs to be a reality check and how important that will be, otherwise a sport will fail or will be a piecemeal process unless there is more funding brought to the table and that is not reducing other funding.”

Strategies to address the challenges to safer sport

To keep the wheels of culture change turning, the sport sector should undertake what high performance coaches and administrators have identified as key challenges to this process. Here we share some strategies directed at oiling the gears to keep the Canadian sport system moving toward realizing a safer culture:

- Reflect on the inherent risk involved in competitive physical activity and what that means for athlete safety (not just the physical risk of high level training and movement, but in the context of maltreatment). Adopt an athlete-centered determination of what is acceptable risk that also accounts for their perceptions of maltreatment. Sport for Life’s Safe Sport Strategy sums up this sentiment well: “Safe sport isn’t just about whether participants are physically safe, but perhaps more importantly, do they feel safe?” (p. 2). Addressing the conundrum of inherent risk in sport may also help to quell the existing turbulence and instability in the safe sport movement.

- Clarify and effectively communicate about jurisdictional responsibilities for addressing maltreatment in sport. At the same time, address jurisdictional differences and pursue better alignment, including common language, approaches and practices, as part of an effective foundation for safer sport within sports and across the sport system. Canada’s Office of the Sport Integrity Commissioner (OSIC) can play a key role in addressing challenges related to sport system alignment, jurisdictional differences, and common language.

- Acknowledge, but do not necessarily accept, different interpretations of “safe” or “unsafe” behaviours and practices in sport. This may be one of the trickiest challenges to address. Education must acknowledge the reality of different interpretations and help coaches and administrators unlearn preconceived ideas of acceptable behaviour (Cegarra-Navarro & Wensley, 2019) and relearn athlete-centered meanings of what “safe” looks like in their sport. The Universal Code of Conduct to Prevent and Address Maltreatment in Sport (UCCMS) provides common principles and standard definitions, and may be used as a resource to manage different interpretations of safe sport.

- Acknowledge and address the general hesitation (or avoidance) of a shift to safer sport. The hesitation described by the sport leaders in our study seems to lie within a general fear of the unknown or doing something wrong. Further education and awareness campaigns are clearly needed. Using the other strategies described in this section may also help to overcome challenges related to hesitation to or fear of change.

- Strategically build human resource and financial capacity for culture change by (1) determining capacity needs and gaps, (2) identifying alternative means to address the identified needs (such as hiring a new position, shifting funding, or establishing a community of practice), and (3) assessing organizational readiness for the initiative (such as willingness to engage in the initiative, alignment with existing processes, or existing capacity to support).

It is important to be aware of, and strategically address, the challenges to building safer sport cultures identified by the high performance sport leaders in our study. At the same time, we must be open to other challenges as they come to light. This is an important piece of the culture shift in high performance sport, along with increased discussion and involvement of key stakeholders’ views to shape both policy and behaviour change. Having a shared vision for what sport can and should look like in Canada is a high priority for realizing this shift, highlighting the need for coaches and administrators, the stewards of culture, to work together in this worthy pursuit.