Highlights

- Concussion recovery depends on many factors, including biological factors (for example, anatomy) and gender-based factors (for example, societal norms in sport).

- Research shows that female athletes have a higher risk of concussion than male athletes, male and female athletes experience concussions in different ways, and female athletes may take longer than male athletes to recover from a concussion.

- Everyone plays an important role in promoting concussion education, improving athlete safety, detecting concussions and supporting athletes in the event of a concussion.

- Sports need a tailored approach to concussion management.

Improving concussion care and prevention in girls, women, and female athletes has become an area of increased interest and importance for many coaches, team trainers and rehabilitation specialists. This is especially true as more and more research points to potential negative consequences that multiple concussions can have on brain health. For example, a person who sustains multiple concussion may have an increased risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (Hay et al., 2016).

Tailoring concussion management and prevention strategies to the specific needs of girls, women, and female athletes is important to create safer sport environments and ensure that these groups can continue to enjoy the many benefits that sports has to offer. This article highlights current research exploring how biological sex and gender can influence concussion risk, management and prevention. Additionally, we identify strategies that coaches, team trainers and rehabilitation specialists can use to better recognize, manage and prevent concussions in girls, women, and female athletes.

Tailoring concussion management and prevention strategies to the specific needs of girls, women, and female athletes is important to create safer sport environments and ensure that these groups can continue to enjoy the many benefits that sports has to offer. This article highlights current research exploring how biological sex and gender can influence concussion risk, management and prevention. Additionally, we identify strategies that coaches, team trainers and rehabilitation specialists can use to better recognize, manage and prevent concussions in girls, women, and female athletes.

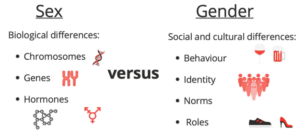

Throughout this article, we use words drawn from the type of research being described. We only use the term female when research refers specifically to biological sex (that is, an individual’s biological attributes such as chromosomes, genes and hormones assigned at birth). Otherwise, we use the terms girls and women when referring to gender (that is, socially constructed roles, behaviors and expressions that form one’s identity).

What is a sport-related concussion, and how does it affect the brain?

A sport-related concussion is a traumatic brain injury resulting from a hit to the head, neck or body that causes a sudden jarring of the head. For example, a sport-related concussion may occur when an athlete falls to the ground, receives a bodycheck, or is struck in the head with a piece of equipment.

This direct and often sudden impact causes the brain to accelerate within the skull, causing damage to important brain structures. This damage is the cause of common concussion symptoms such as difficulties with concentration and memory. When an athlete follows proper return-to-play protocols, damage to the brain can be short-lasting, often resolving on its own in 85% to 90% of cases (Thornhill et al., 2000; Whitnall et al., 2006). But for a small proportion of athletes, this damage can have long-lasting effects on daily activities such as attending school or work.

Axons are fibre bundles that are responsible for transmitting information between different areas of the brain. When a person sustains a concussion, their brain’s axons are injured (Alexander et al., 2010). Damage to the brain’s axons is called diffuse axonal injury (DAI). DAI can lead to changes in the brain’s structure and function (Gardner et al., 2014; Multani et al., 2016; Pasternak et al., 2014) and have a negative impact on cognitive processes such as attention and memory (Hsu et al., 2015; Czernick et al., 2015).

Female athletes have a higher risk of concussion than male athletes

Research suggests that female athletes may be at an increased risk of concussion when compared to male athletes. For example, researchers in one study found that concussion risk for female soccer players is around 1.8 times higher than for male soccer players (Bretzin et al., 2021).

Female athletes may be at greater risk of sustaining a concussion than male athletes, in part because they’re more vulnerable to DAI (Rubin et al., 2018; Sollmann et al., 2018). In other words, when a female axon is exposed to the same force as a male axon, the female axon is more likely to be more damaged (Dolle et al., 2018). The reason for this increased risk of DAI is because female individuals generally have smaller axons and fewer microtubules, compared to male individuals. Microtubules are microstructures that support axons.

But it’s not just the brain’s structure that contributes to female athletes’ increased risk of concussion. Decreased neck strength and a smaller neck size may also contribute to the higher concussion risk seen in female athletes. This is because weaker neck muscles have been associated with more head acceleration during an impact (Honda et al., 2018). With stronger neck muscles, female athletes may experience less head motion during an impact, therefore reducing concussion risk (Honda et al., 2018).

Given that multiple factors can predispose female athletes to concussions, their coaches, trainers and rehabilitation specialists may consider the following injury prevention and risk reduction strategies:

- Incorporate strength training for neck muscles. Adding isometric neck strength training to a female athlete’s workout routine may help to reduce their risk of injury.

- Ensure athletes wear a properly fitted helmet. When a helmet fits properly, it can reduce the severity of a concussion (Greenhill et al., 2016). Encourage female athletes to check the fit of their helmet regularly, particularly those who change their hairstyle frequently (for example, from a braid to a bun).

Male and female athletes experience concussions in different ways

DAI causes damage to the brain’s structure, which can affect how messages are sent from one area of the brain to another. At least in the long term, concussions appear to impact male and female participant’s brain connectivity, and in turn function, in different ways (Shafi et al., 2020).

Research has shown that female participants who have sustained a concussion experience more changes in communication between the brain regions that specifically support goal-directed behaviour. In contrast, male participants who have sustained a concussion tend to experience changes in communication between the brain regions that guide behaviour based on cues from the internal or external environment.

What does this mean? While both male and female athletes may experience challenges after experiencing a concussion, the types of challenges they face may differ depending on the parts of the brain that are affected. For example, female athletes may have difficulty completing a new drill because they have trouble planning the steps and/or developing strategies needed to complete it.

Alternatively, male athletes may have difficulty completing a new drill because they’re unable to filter out distractors in their internal environment (such as negative thoughts about their performance) or external environment (such as cheering or heckling from spectators).

While more research is needed to understand how biological sex influences sport-related concussions, we offer the following recommendations:

- Coaches: Consider how biological (sex-specific) differences may impact an athlete’s learning and adapt your teaching strategies accordingly. For example, when working with a female athlete who has experienced a concussion, consider budgeting extra time to break down a new skill or drill when it’s safe for them to return to sport.

- Rehabilitation specialists: Consider what internal factors (for example, functional brain changes) may be contributing to an athlete’s difficulties post-injury and work to tailor their management plan accordingly. Remember, when it comes to concussion management, an individualized and patient-centred approach is needed!

Female athletes take longer than male athletes to recover from a concussion

Coaches, team trainers and rehabilitation specialists play an essential role in encouraging an athlete to follow the appropriate recovery protocols. Given the structural and functional differences in a female athlete’s brain, it may be even more important to have an informed and individualized approach to concussion recovery.

Research suggests that female athletes often take longer to fully recover after a concussion compared to male athletes (Covassin et al., 2018). These longer recovery times may be associated with the greater symptom burden (meaning a greater number and severity of symptoms) often reported by female athletes after their injury.

However, longer recovery times may also be linked to differences in concussion care for male and female athletes. Unfortunately, research suggests that compared to male athletes, female athletes are around 1.5 times less likely to be immediately removed from play after an injury (Bretzin et al., 2021). This variability in immediate, sideline care may also reflect differences in gender norms in sport. It also highlights the importance of considering both sex and gender when managing concussions.

Since the return-to-play process will look different for all girls, women, and female athletes, it can be helpful to have concussion testing data as a baseline comparison to help assess when the athlete is ready to get back into play. While not mandatory, baseline testing can be helpful as it allows rehabilitation specialists to determine when an athlete has returned to their “healthy” or “baseline” state (McCrory et al., 2017). Without this data, it can be difficult for rehabilitation specialist to determine when an athlete has returned to their pre-injury or “healthy” state, which may delay their return-to-play.

How can you help a girl or women through their return to play?

The first step in helping an athlete return to play is to recognize when a concussion may have happened. And then, remove the athlete from play so that they can be assessed and can start the appropriate return-to-play process. Throughout this process:

- Familiarize yourself with the signs and symptoms of a concussion so that you are able to identify when an athlete has sustained an injury.

- Follow SIRC’s 4 R’s (Recognize, Remove, Refer, Return) of concussion management to ensure that the athlete gets the care that they need.

- Use Parachute Canada’s return-to-sport guidelines or your sport-specific, return-to-sport protocols to help guide the athlete’s return to play.

- Understand that all athletes will recover from a concussion differently, so it’s important to tailor return-to-play protocols to the unique needs of each girl, woman, or female athlete.

Lastly, it’s important to recognize that the concussion recovery process can be overwhelming for an athlete. In fact, research shows that girls often report more negative emotions (such as frustration) around concussion recovery than boys do (Claire et al., 2020). As such, it’s essential that coaches, team trainers and rehabilitation specialists provide support early on and throughout their recovery (Clair et al., 2020). To help support the recovery process, coaches, team trainers and rehabilitation specialists can:

- Educate the athlete about their likelihood of making a full recovery. Knowing how likely they are likely to recover completely has been shown to have a positive impact on recovery outcomes (Bazarian et al., 2020)

- Accommodate the athlete’s needs. For example, when the athlete has received medical clearance to reintroduce sport-specific activities into their training, consider altering drills to be contact-free to support safe participation.

- Check in on the athlete to see how they’re doing, let them know that they’re missed and reassure them that their spot on the team will be waiting for them whenever they can safely return to play. Check-ins can help the concussed individual feel included and highlights that you’re there to support them (Kita et al., 2020).

Conclusion and next steps

Concussion research involving girls, women, and female athletes has grown significantly over the past decade. Despite progress that’s been made, there’s still work to be done. This includes gaining a deeper understanding of factors that contribute to increased risk of injury and the long-term effects of a concussion on the health and wellbeing of girls, women, and female athletes.

It’s important to remember that each athlete will require an individualized approach to concussion management and prevention. As researchers and other sport stakeholders work toward making sport safer, coaches, trainers and rehabilitation specialists can use the recommendations provided in this article to reduce the known risks of concussion that seem to be more prevalent for girls, women, and female athletes.