In recent years public awareness and concern about climate change have significantly increased. Organizations are increasingly acknowledging and addressing the direct link between their operations and climate change, embracing initiatives from paper straws to carbon offsets. However, as climate impacts intensify globally, and with both governments and corporations falling short of making sufficient progress on their commitments to reduce global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; there has been an increase in pressure from the public for organizations to take accountability and meaningful action to reduce their overall environmental impact. This, coupled with climate change related legal and regulatory frameworks growing more strict, organizations are now forced to more seriously consider the impacts of their operations on the environment and the impact of the changing climate on their own operations.

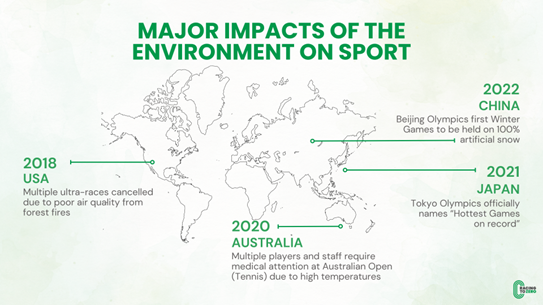

Here’s where we introduce the concept of ‘Sport Ecology’, which is the study of the bidirectional relationship between sport and the natural environment (McCullough, Orr & Kellison, 2020). We’ve started to see an increasing number of headlines linking the two, and specifically demonstrating the influence that climate has on sports. From poor air quality caused by forest fires to extreme heat at competitions, environmental ’events’ like these put an immense strain on everyone involved in sport. Athletes have to compete in difficult conditions, event organizers battle to make sure their competitions go off without issue. One example is the marathon race at the Tokyo 2020 Summer Olympics, which was moved from Tokyo to Sapporo due to excess heat. This directly impacted athletes, fans and organizers, as well as the knock-on effects in terms of transportation, facility development, and execution of the event.

While most sports are inherently affected by the natural environment, they also have a significant impact on the environment. How is this manifested? A perfect example of this bi-directional relationship was the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics, which were the first to be held on 100% artificial snow. While this could be attributed to the warming climate, the water usage and energy consumption required to produce that much snow has a significant carbon footprint, which will only lead to similar events in the future if not managed effectively. Other key areas in which sport can produce a negative effect on the environment include emissions from travel to training and competition, energy consumed by large facilities, emissions associated with the waste generated by producing equipment and clothing, and higher emissions from meat-intense diets of the majority of athletes.

So, what can be done about this?

Clearly, it is time for sport organizations to step up and prioritize sustainability efforts, which begins with getting a better understanding of key impact areas. Various initiatives and groups already exist, seeking to create lasting change. Some examples include our business, Racing to Zero, which is a Sport and Sustainability Consultancy led by a group of Canadian Olympians working with sport organizations of all sizes to help understand, measure and reduce emissions. The Green Sports Alliance is the largest, most influential, and initial driver of environmental action across the global sports industry. They also helped create Green Sports Day, which exists on October 6th each year to unite the sporting community around a more sustainable future. Another is the Climate Positive Energy group out of the University of Toronto, which is less directly linked to sport but helps drive improvements through research.

While these are some steps in the right direction, it is more imperative than ever to begin measuring and addressing global carbon emissions if we are to reach our net zero targets. We believe in the incredible power that sport has to inspire change and want to see Canada become a leader in using sport to drive meaningful environmental action.

Canadian sporting landscape

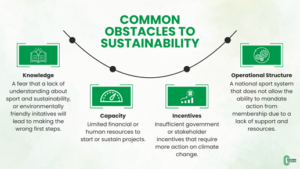

Canada is a relatively progressive country when it comes to climate change. The government of Canada has an Emissions Reduction Plan providing a roadmap for the Canadian economy to achieve 40-45% emissions reductions below 2005 levels by 2030, but uptake of actionable change has been slow within the sport sector. In our work, we have found that there are 4 common obstacles that keep organizations from taking their first steps in sustainability:

- Knowledge: A fear that their lack of understanding about sport ecology will lead to making the wrong first steps.

- Capacity: No financial or human resources to start or sustain projects.

- Incentives: Insufficient government or stakeholder incentives that require more action on climate change.

- Operational structure: An inability to mandate action from membership due to how sport is structured in Canada.

We have also found that these 4 obstacles often play into each other, compounding the problem further.

- We start with a genuine absence of knowledge about the topic, or the fear of not knowing enough, both regarding the general issue and the methods to solve it. While this may be true, and climate change is a deep and complex subject, there is often no way for organizations to take the time to learn more about it due to a lack of capacity.

- Sport organizations of all levels are already stretched so thin that there may be no room in any schedule to do the necessary research to understand the impacts and make a plan for improvement. The next logical step is to outsource the sustainability work to experts but with the way sport is structured and funded, performance on the field of play takes precedence over ancillary considerations so there is rarely any budget remaining to hire a sustainability consultant.

- So where do organizations turn to next? Incentives for this type of work, especially in the sporting context, simply don’t exist at a large enough scale to support meaningful change.

- Which finally leads us to this inability to mandate action from organizations at every level due to this lack of the necessary support structures in place.

Luckily, despite the challenges there have still been organizations prioritizing their environmental impact and committing the necessary resources to understanding and reducing them. At the highest level, the IOC has included sustainability in its planning since as early as 1992, incorporating more and more initiatives in each edition of the Games. In fact, it was the IOC’s Young Leaders Program that gave Oluseyi Smith the initial funding to start Racing to Zero.

Elsewhere, the World Surf League is leading the path forward for International Professional Bodies by signing on to the UN Sports for Climate Action Framework in 2018, which includes a series of sustainability targets and the structure necessary for the organization to support global emission targets tied to limiting global warming.

In a similar fashion, SailGP is striving to be the most purpose-driven global sports platform. SailGP even changed its competition structure to include an “Impact League”, which runs in tandem to its season and tracks the positive actions that teams make to reduce their overall carbon emissions and awards cash prize donations to the winners.

Case studies:

Looking more inwardly here in Canada, we had the opportunity to work with some incredible organizations in the short time since establishing. In 2022, we were approached by Curling Canada with a challenge that we have heard before many times. They were aware that activities throughout the entire organization were having an adverse impact on the environment, and they wanted to take action but didn’t know where to begin (Obstacle #1). Luckily, through strong leadership, then-CEO Kathy Henderson committed the necessary resources towards taking the first steps.

Our project had 3 phases. First, we hosted a sustainability strategic planning workshop with a diverse set of Curling Canada’s members to learn more about their respective sustainability priorities and the organization itself. We then completed comprehensive carbon inventories for 3 of their events, including the 2023 Brier and 2023 Men’s World Curling Championships. Finally, using the information collected and after thorough analysis, we provided recommendations for developing Curling Canada’s own sustainability strategy. One of the project leads and current CEO of Curling Canada, Nolan Thiessen, was pivotal to the success of the project, citing that with anything in sport, “we always have to improve, and this is another area we can improve.” At the end of the project when debriefing on the process, he highlighted that communicating with internal stakeholders was one of the most important aspects for ensuring a successful project, however, “it wasn’t that major of a lift once we understood what was being requested.”

Curling Canada is not the only sport organization that is ramping up their sustainability efforts. Canada Games Council, a leader in Canada’s sporting landscape, has formal commitments, performance metrics, and a dedicated sustainability and impact staff. As part of this strategy, the Canada Games Council is measuring its 2023 corporate emissions.

Large organizations should not be the only ones thinking about sustainability. Organizations of all sizes should consider their impact and have a proactive strategy for navigating the evolving landscape while managing the risks and opportunities associated with environmental engagement. A key piece in the process is to ensure organizations of all sizes have equal access to resources. For example, when working with Athletics Ontario, we assisted with calculating an emissions baseline for an event, as well as provided an educational workshop to help race directors understand major areas of impact to focus on when planning future meets. For a provincial organization with multiple requests of its discretionary funding, including sustainability in their strategic pillars establishes them as a leader in the space. It sends an important signal to the Canadian sport system that sustainability is top of mind, which is essential in driving systemic change.

Paris Olympic and Paralympic Games

Looking from a wider lens, the Paris 2024 organizing committee has set some ambitious goals for the Olympic and Paralympic Games this summer, setting an example for all others to follow. Their mission is not only to host the “greenest” Games yet, but to establish a new model for hosting Games that strives for a positive impact on the climate, instead of negative. The Legacy and Sustainability Plan outlines the organizing committee’s objectives and implementation strategies for both environmental and social impact, with a strong focus on both the present and the future. The plan provides details and rationale for all, but here a few key highlights regarding environmental sustainability:

Major promises:

- $76 million CAD dedicated to the ‘Environmental Excellence Strategy’.

- Halve the total emissions from the Rio and London Games (3.6m to 1.5m tonnes CO2e).

- Protect and regenerate the native biodiversity of the region.

- Establish a circular economy.

- Bolster climate resilience.

- Promote the development of sustainable technologies.

Key elements of the strategy:

- Assigning a ‘Carbon Budget’ that must be adhered to, similar to a financial budget.

- A systematic method to analyzing and measuring impacts across all aspects of the Games.

- Developing an iterative assessment tool for environmental impact during planning.

- Using 95% existing infrastructure.

- Creating a Responsible Purchasing Strategy that incorporates circular economy principles of design, and that must be signed and adhered to by all Games contractors and suppliers.

- Creating a Resource Management Plan, again with circular economy principles of design incorporated.

- Using renewable energy for temporary structures.

- Shifting towards sustainable catering, with more local, organic and plant-based meals provided.

- Using venues only within a 10km radius and can be accessed easily by public transportation.

Other aspects of note:

- The environmental focus on sustainability was incorporated into the bidding process, not as an afterthought.

- It is the first Games to be aligned with the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

- All trade unions and employer organizations signed the ‘Paris 2024 Social Charter’, agreeing upon benchmarks for social relations and impact measurements.

- Efforts undertaken to achieve ISO 20121 (Sustainable Events) certification.

- Added to the standard “Avoid, Mitigate, Offset” framework for emissions reductions to create a more comprehensive “Anticipate, Avoid, Mitigate, Offset, Catalyze Action.”

Mass adoption

The Olympic and Paralympic Games are some of the largest sporting events in the world, attracting viewership in the billions (International Olympic Committee, 2022). The sustainability and legacy plan for Paris focuses on changing the model for organizing and hosting sporting events, which will hopefully drive change in smaller scale events across the world.

The fact that the IOC is placing such a strong emphasis on environmental sustainability should be inspiring to all those organizations that fall in that same realm. As a collective, Canadian sport organizations have an opportunity to follow the IOC’s lead and take action to first understand and then reduce their impacts. The Paris Games offer organizers a path forward to less carbon-intensive events by sharing numerous resources, toolkits, and publications to forge a path to less carbon-intensive events. However, the way to create the most meaningful change is through a systemic shift in priorities within organizations. Paris has shown how ingraining sustainability deep into a core strategy can create opportunities for ambitious targets to be met. This can be replicated by sport organizations of any size to address impacts on a much larger scale and make so-called “green” events the new norm, in addition to everyday operations, training and international competitions.

Call to action

As stakeholders’ expectations continue to rise, and more than ever sponsors, athletes, and the general public are expecting sport organizations to take accountability and make efforts to reduce their impact on the environment; we believe now is the time to act. Sport has the power to help shift towards a more environmentally-conscious and low-carbon future. Despite the challenges, we encourage all sport administrators, organizations, clubs, and athletes to consider their environmental impact and take steps to improve:

- Educate: Research and learn what your major emissions sources are and understand the impact that they have.

- Establish baselines: Measure your impact (across events, teams, or the entire organization) to have something to compare against.

- Set targets: Consider priorities and set realistic, science-based targets to reduce emissions.

- Establish strategies to improve: Create strategies and action plans to reach those targets and engrain sustainability as a core aspect of your business.

About the Author(s)

Oliver Scholfield is the Executive Director of Racing to Zero, a sport and sustainability consultancy working with sport organizations to help them understand and reduce their environmental impacts. He holds a Bachelor of Science in Natural Resource Conservation and a Master of Management degree, both from the University of British Columbia. He competed in the 2020 Olympic Games in field hockey and played over 100 caps for the Men’s National Team from 2014-2024. He is based in Vancouver, on the traditional, ancestral, and unceded territory of the Coast Salish peoples, including the territories of the xʷməθkwəy̓ əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and Səl̓ílwətaʔ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations.

References

UNFCCC. (n.d.). Climate plans remain insufficient, more ambitious action needed now. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://unfccc.int/news/climate-plans-remain-insufficient-more-ambitious-action-needed-now

Gilder, A., & Rumble, O. (2023). Climate Change Regulation 2023. Chamber and Partners. https://practiceguides.chambers.com/practice-guides/climate-change-regulation-2023

McCullough, B. P., Orr, M., & Kellison, T. (2020). Sport ecology: Conceptualizing an emerging subdiscipline within sport management. Journal of Sport Management, 34(6), 509–520. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2019-0294

Government of Canada. (n.d.). Climate plan overview. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/en/services/environment/weather/climatechange/climate-plan/climate-plan-overview.html

International Olympic Committee. (2022, February 25). Olympic Winter Games Beijing 2022 watched by more than 2 billion people. Retrieved from https://olympics.com/ioc/news/olympic-winter-games-beijing-2022-watched-by-more-than-2-billion-people

The information presented in SIRC blogs and SIRCuit articles is accurate and reliable as of the date of publication. Developments that occur after the date of publication may impact the current accuracy of the information presented in a previously published blog or article.