50 years of Indigenous sport in Canada: An overview of 2 key advancements and challenges

November 27, 2023

‘Girls’ Pole Push Competition at the Dene Games Competitions’, Arctic Winter Games 2010, Grande Prairie Alberta, March 2010 (Photo: Michael Heine)

Imagine what sport in Canada might look like had Indigenous peoples and their cultures not been colonized? Imagine how Canadians might understand who they are and their relationship to each other if Indigenous sports and games were part of their daily lives? Imagine what values and beliefs Indigenous sports and games might teach Canadians today? Sadly, these questions that invert history are hypotheticals because colonialism, and the settler colonialism that followed, caused serious harm to Indigenous cultures.

The 19th and 20th century were incredibly hard for the First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples in Canada. During that time, they had to make the difficult transition from their land-based lifestyles to living on reserves and settlements, which were poorly resourced. They struggled through disease and starvation. Many of them watched their children being sent far away to residential schools, where they were provided with an impoverished education. Or, through the Sixties Scoop, their children were taken from their homes and placed with white families, never to be seen again. Nearly every Indigenous person wrestled with their loss of language, culture, and identity, in addition to poverty and poor mental and physical health, resulting in a phenomenon called “intergenerational trauma” (also referred to as transgenerational trauma or historical trauma) that Indigenous peoples are working through today.

The state used Euro-Canadian sports to both hasten the process of Indigenous assimilation and to make it complete. Government and church leaders, along with the white middle-class reformers who led the development of Canada’s fledgling sport system, widely believed their version of sports would help civilize the masses and produce a hard-working, patriotic citizenry. They believed their sports were especially productive for socializing Indigenous peoples into Canadian culture because, in their racist imagination, Indigenous peoples were biologically ‘naturally’ good athletes who would willingly take up the new sport forms and, in doing so, readily abandon their traditions, as if Indigenous physical practices were hobbies and not the deep connective tissue that sustained their ways of life and their connections to land. The government even formalized this dogma when, in 1884, it enacted the Potlatch Law through Section 141 of the Indian Act, a federal statute that (still) governs all matters concerning Indian status, bands, and reserves in Canada.

Potlaches, a gift-giving feast that was traditionally used to mark a variety of important milestones and occasions in West Coast tribes and customs, and as a way of celebrating life, were banned first; even though they were a vital part of west coast Indigenous cultures. Other ceremonial practices, like the sun dances that were central to Indigenous cultures on the prairies, were soon added to the list. To fill the void, the government encouraged Indigenous peoples to play Euro-Canadian sports instead. This is when “Indian Sports Days” emerged on reserves; they were usually held in conjunction with national holidays and treaty-day celebrations to reinforce the connection between sports and patriotism. In other words, from a statist point of view, making Indigenous peoples participate in Euro-Canadian sports was important for cultural repression and replacement.

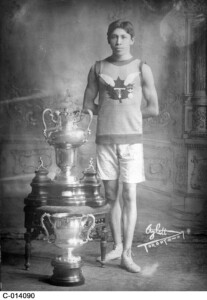

Indigenous peoples did engage in sports and many, especially boys and men (who had more opportunities to play and compete), succeeded in spite of the hard obstacles in their way. The long list of names that comprise the Tom Longboat Awards, established in 1951, is an obvious reminder of their constant presence and achievements in Canadian sport. At the same time, the Awards’ history also demonstrates how much things have changed for Indigenous peoples in sport. The federal government through Indian Affairs created the Awards to stimulate assimilation by rewarding athletes who excelled at Euro-Canadian sports. But by the early 1970s, as Indigenous peoples began to exert their self-determination more broadly, they wanted greater control of the Awards to promote their own messages about integration.

The nomination letter for Doug Skead, from the Wauzhushk Onigum Nation (formerly Rat Portage Band near Kenora, Ontario), who would be named the 1971 national Award recipient, is a case in point. His nominator, Peter Kelly, writing on behalf of Grand Council Treaty No. 3, the political organization representing Treaty 3 interests in northwestern Ontario and eastern Manitoba, described Skead as a role model for his people, not because he had acculturated as the state hoped, but because he represented “the Indian person who will always remain undefeated,” thus using a common sports reference to make a strong statement about what “undefeated” meant to them. Kelly explained that Skead had come “through the demoralizing era of residential schools, the tough life of a trapper, guide and wood cutter, and the destructive experiences of alcohol, to become the manager of his band’s corporation and captain of the hockey team he co-founded 20 years before.” When asked by a reporter what advice he would give to youth, Skead, 41 years old, said “hold on to their culture and speak their native language” (cited in Forsyth, 2020).

Indigenous sport has grown tremendously since the 1970s. There are now more Indigenous-only events and more recognition and support for Indigenous sports and Indigenous participation in sports than ever before. The North American Indigenous Games (NAIG) signifies this growth. First held in 1990 in Edmonton, Alberta, the NAIG functioned for many years on a shoe-string budget and struggled with administrative capacity. That it survived those early years was due mostly to Indigenous leaders who were intent on providing their youth with an opportunity to experience competition in a culturally affirming environment. More than 30 years later, the NAIG is now the largest multi-sport gathering for Indigenous youth on the continent as well as an institutionalized part of the Canadian sport system supported by all 3 levels of government and major corporations. As with any system, there are still important challenges to address, which means sport and government leaders need to remain alert to the broader factors that shape Indigenous sport in Canada.

What follows are 2 key advancements, along with their continuing challenges, that have occurred over the past 50 years:

1) Strengthening the Indigenous sport system

In Canada, there exists an Indigenous sport system that is separate from, but connected to, the mainstream sport system. The term “mainstream” refers to the traditional Euro-Canadian or prevailing system of sport in Canada, made up of national, provincial and territorial, and community sport organizations. The relationship between the two can be visualized as a ‘double helix.’ Just as the physical structure of DNA is made of 2 independent strands that are supported by cross-links forming a ladder-like shape, Canadian sport is comprised of an Indigenous sport system and a mainstream sport system that connect at relevant points, creating possibilities for each system to benefit from each other, resulting in a stronger ladder. Even though the Indigenous sport system has been in place for more than a half century, there remains a general lack of knowledge about it, which makes it harder for Indigenous sport leaders to secure the resources they need to serve their peoples and communities, as well as support mainstream partners in their efforts to better serve Indigenous needs and interests.

The Indigenous sport system, as a separate system with governing bodies, rules, and events, emerged in the early 1970s, when Fitness and Amateur Sport, the precursor to Sport Canada, was looking to increase the participation rates of ‘disadvantaged’ Canadians in organized sports and identified Indigenous people as a group needing specific attention. The result was the Native Sport and Recreation Program, which was created to increase sport and recreation opportunities for Indigenous people on and off reserves. From 1972 to 1981, the program flourished as Indigenous organizers throughout the country coordinated local, regional, and national activities in a wide range of events that addressed pressing community issues stemming from colonialism, like the alarming suicide rates, substance abuse, high drop-out rates of students, and violence among families. Even though the program flourished, it was terminated in March 1981 when the federal government shifted its priorities from mass participation to elite sport development.

With the new focus on competitive outcomes, reviewers of the Native Sport and Recreation Program concluded that the range of pursuits fostered by Indigenous organizers like ‘cultural’ activities versus organized sports was outside the scope of initiatives the funding was meant to support and that the programs developed by Indigenous organizers would not produce the high-performance results desired by the federal government. During that time, however, Indigenous sport organizations were established in each province and territory with the mandate to develop activities within their regions. Those organizations are the forerunners to the Provincial and Territorial Aboriginal Sport Bodies (PTASBs) that today comprise the membership of the Aboriginal Sport Circle (ASC), the national voice for Indigenous sport in Canada.

Today, the power imbalance, and the unequal access to resources, knowledge, and capacity, between the Indigenous sport system and the mainstream sport system has been partially addressed in that there is more consistent support for PTASBs and the ASC than before. Strengthening the Indigenous sport system will require governments and other funders to adjust the way they support Indigenous sport by providing multi-year agreements to stop the annual cycle of uncertainty, as well as foster collaboration across government jurisdictions, like sport, education, and health, so that more Indigenous peoples can use sport to address the critical issues they face.

2) Revitalizing traditional Indigenous sports

Prior to European settlement, Indigenous peoples had their own sports and games. Their activities, rooted in their land-based lifestyles, spirituality, and views of the universe, were perfectly geared for life on the land. How many Indigenous sports and games there were prior to European settlement is hard to say. Each Indigenous nation, community, and family would have had their own practices, some of which would have been shared across groups and regions, as they travelled from one place to the next meeting, greeting, negotiating, and engaging in competition, as well as ceremony, with other Indigenous peoples.

Present-day language statistics provide one indication of how diverse Indigenous physical cultural practices might have been. Using 2021 survey data, Statistics Canada reported that over 70 Indigenous languages are still spoken in Canada, though that number is decreasing at a worrisome rate, with 4.5% fewer Indigenous people reporting they could carry on a conversation in an Indigenous language and 7.1% fewer Indigenous people reporting an Indigenous language as the first language they learned at home (down from 2016 data). Those statistics are even more distressing in light of UNESCO’s 2010 assessment that all Indigenous languages in Canada are endangered, which prompted the federal government to create the Indigenous Languages Act in 2019 to preserve, promote, and revitalize them. The number of languages still in use today is important because it indicates how many different Indigenous nations are still present and their determination to each keep their language alive. Each nation would have also engaged in their own collection of sports and games, which means Indigenous physical culture prior to colonization, much like Indigenous languages, would have been extremely rich and varied.

Though colonialism has extinguished much of Indigenous physical culture, some of that culture is still seen today. The Haudenosaunee (Mohawk) game of lacrosse is one example. While most non-Haudenosaunee people will know of the competitive version, the game that Montrealer William George Beers appropriated from the Haudenosaunee in the latter half of the 1800s (and then banned from league play), few people may know that traditional forms of lacrosse are still practiced for ceremonial reasons at the community level. Lacrosse was never just about sport to the Haudenosaunee.

The games of the Inuit and Dene peoples in the far north are another example. They were worried about their youth losing their sense of identity, which was rooted in the land. Since they no longer relied on the land to sustain them, they transformed their sports and games into modern competitive formats to remind their youth about who they are and to instill pride in their culture. The Inuit and Dene Games, which are now part of the Arctic Winter Games, are an institutionalized part of the Canadian sport system.

Traditional Indigenous sports and games are still a vital part of Indigenous cultural transmission, though they too are endangered, perhaps even more so than Indigenous languages. But unlike Indigenous languages, there are no statistics that track how many Indigenous people engage in their sports and games today, where they learned how to play them (was it in the home, at school, or a community gathering?), how often they play or compete, or why they do so. The lack of information benefits settler colonialism, which is the ongoing removal of Indigenous peoples from their lands by erasing their cultures and identities. While Indigenous peoples throughout Canada are working hard to keep their cultures alive, there remains a significant amount of work to do where their traditional sports and games are concerned.

About the Author(s)

Janice Forsyth, member of the Fisher River Cree Nation (Manitoba), is an award-winning scholar whose research, service, and advocacy focuses on Indigenous sport development in Canada. Her work combines history and sociology to explore the relationship between sport and culture from Indigenous points of view. Her work has informed policy and program development across sectors, including youth and community development, justice, education, citizenship, and health, in addition to sport and physical activity. Her co-edited collection, Aboriginal Peoples and Sport in Canada: Historical Foundations and Contemporary Issues (2013), is a standard text in many classrooms throughout Canada, while her recently released monograph, Reclaiming Tom Longboat: Indigenous Self-Determination in Canadian Sport (2020), won the Ontario History Award for Indigenous History as well as the North American Society for Sport History’s Best Monograph Award. She is a Professor in Indigenous Land-Based Physical Culture and Wellness in the School of Kinesiology, Faculty of Education, at the University of British Columbia.

References

Downey, A. (2018). The creator’s game: Lacrosse, identity, and Indigenous nationhood. UBC Press.

Forsyth, J. (2020). Reclaiming Tom Longboat: Indigenous self-determination in Canadian sport. University of Regina Press.

Forsyth, J. & Paraschak, V. (2013). The double helix: Aboriginal people and sport policy in Canada. In L. Thibault & J. Harvey (Eds.), Sport Policy in Canada (pp. 267-293). University of Ottawa Press.

Heine, M. (2013). Performance indicators: Aboriginal games at the Arctic Winter Games. In Forsyth, J. & Giles, A. (Eds.), Aboriginal peoples and sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues (pp. 160-181). UBC Press.

Lavallée, L. & Lévesque, L. (2013). Two-eyed seeing: Physical activity, sport, and recreation promotion in Indigenous community. In Forsyth, J. & Giles, A. (Eds.), Aboriginal peoples and sport in Canada: Historical foundations and contemporary issues (pp. 206-228). UBC Press.

Menzies, P. (2020, March 25). International trauma and residential schools. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/intergenerational-trauma-and-residential-schools

Statistic Canada. (2023, March 29). Indigenous languages across Canada. https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2021/as-sa/98-200-X/2021012/98-200-X2021012-eng.cfm

The information presented in SIRC blogs and SIRCuit articles is accurate and reliable as of the date of publication. Developments that occur after the date of publication may impact the current accuracy of the information presented in a previously published blog or article.