Highlights

- The number of concussions reported among Canadian youth has increased annually by 10.3% between 2004 and 2015.

- Many concussions go unreported by youth due to their lack of knowledge, thinking it won’t make a difference, believing their friends will treat them differently and a lack of self-efficacy.

- Improved concussion reporting and health outcomes may happen by understanding that social networks strongly influenced youth, exploring new ways of enabling youth to help each other learn about concussion and supporting recovery after a concussion.

- The Youth Concussion Awareness Network (You-CAN) is a novel, peer-led program on concussion education and awareness for high-school students across Canada. It provides a platform to explore peer-led concussion education and support. You-CAN also aims to increase behaviours specific to reporting a concussion to an adult and to providing social support to a peer with a concussion.

- Research to evaluate the impact of You-CAN is ongoing in Canadian high schools. Efforts are underway to explore how it can be adapted and used in sport communities, organizations, clubs and leagues.

Youth concussion in Canada is a serious public health concern. Concussions in Canadian youth, aged 12 to 17 years old, have increased annually by 10.3% between 2004 and 2015 (Rao et al., 2018). High-school students experience the highest rates of concussion among all children and youth. Additionally, their concussions are often under-reported. The reasons for under-reporting are suspected to be high-school students’ lack of knowledge about concussions, the influence of their social environment, believing that reporting their concussion wouldn’t help, concern about how they think their peers will react, and a lack of self-efficacy (“Sports-Related Concussions in Youth: Improving the Science, Changing the Culture,” 2015).

In the past, youth with histories of concussion have identified that their social participation during their concussion recovery was affected by their peers’ lack of understanding about concussion (Valovich McLeod et al., 2017). Because youth are strongly influenced by their social networks, peer education can play a big role in students’ knowledge (what they know about concussion), attitudes (what they think about concussion), and intended behaviours (how they would act if they experienced a concussion or if a friend had a concussion).

In this article, we’ll describe You-CAN, our peer-led education program to help high-school students understand concussions. We’ll also define what social support is and how it can help youth with a concussion. Additionally, we’ll explain how youth in sports can help each other with concussion recovery, and how coaches, administrators, parents, and others involved in youth sport can help youth athletes who have sustained a concussion.

What is You-CAN?

The Youth Concussion Awareness Network (You-CAN) is an ongoing research study and education program, funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Its team members and collaborators are located across Canada, and it has been created with project co-lead Parachute Canada. As the first program of its kind, You-CAN uses a peer-led approach that aims to raise concussion awareness among Canadian high-school students, promote positive change in concussion knowledge and attitudes, and foster connections between participating schools and students.

The Youth Concussion Awareness Network (You-CAN) is an ongoing research study and education program, funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Its team members and collaborators are located across Canada, and it has been created with project co-lead Parachute Canada. As the first program of its kind, You-CAN uses a peer-led approach that aims to raise concussion awareness among Canadian high-school students, promote positive change in concussion knowledge and attitudes, and foster connections between participating schools and students.

You-CAN’s overarching goal is to change Canadian students’ behaviours specific to:

- reporting a suspected concussion to an adult

- supporting their peers who experience a concussion

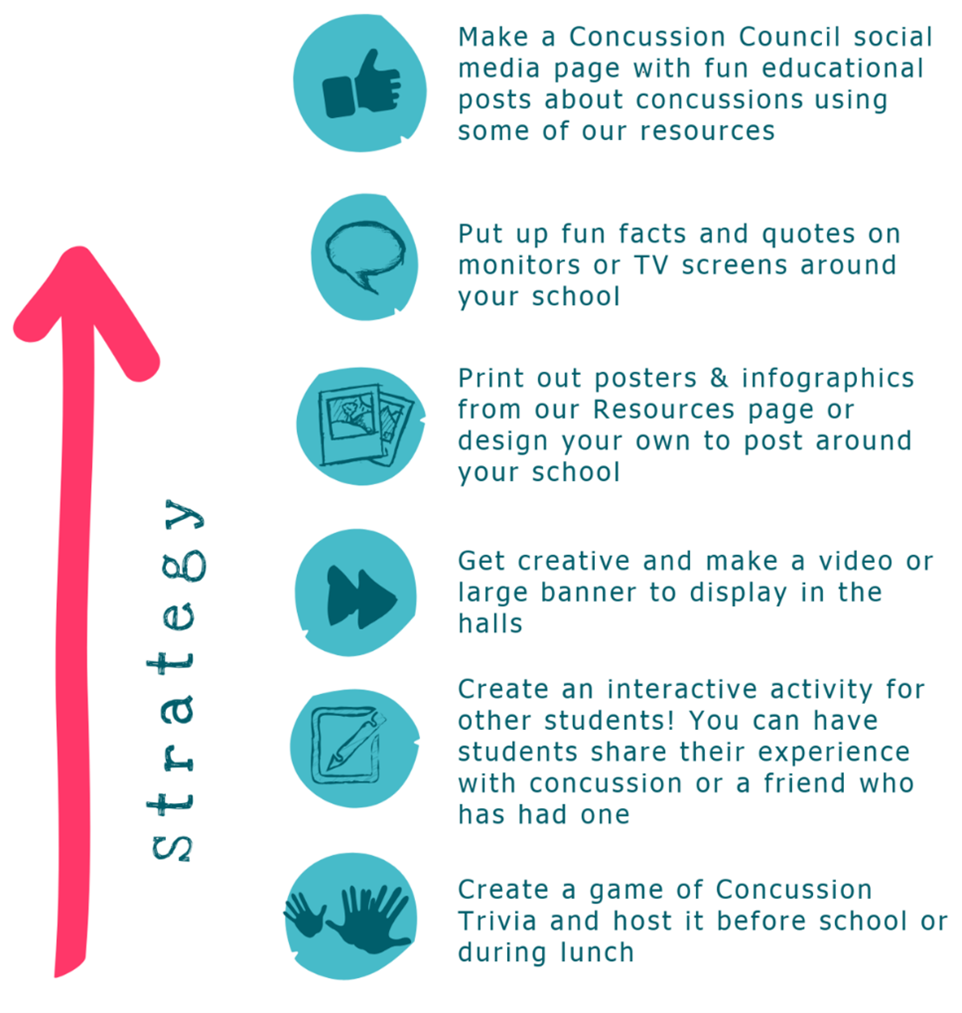

The concept of You-CAN is simple: provide a platform and resources for youth to learn with their peers, and in turn, support their peers. To do this, participating high schools nationwide have created Concussion Councils. Like other clubs and councils within their school, the Concussion Council meets regularly. Members of the Concussion Council plan and execute ways to share information about concussions and provide other students with appropriate concussion resources.

As well, the Concussion Councils create and host annual week-long concussion awareness campaigns within their schools. The Concussion Councils are encouraged to be creative with their campaigns, enabling participating students to create the campaign that they feel best matches the wants and needs of their school community (see Figure 1). To make sure that the campaigns share up-to-date and accurate information, students can access a web-based portal. This concussion resource portal contains evidence-informed, concussion education resources from across North America. We’ve approved these resources using specific criteria to ensure they’re both accurate and written specifically for youth.

To celebrate the incredible work of participating high schools and students, each spring the Concussion Councils will share their work with other councils from high schools across Canada. This will happen during the annual Rowan Stringer Concussion Awareness Campaign Showcase. While the virtual showcase hasn’t started yet because of COVID‑19, it will highlight the efforts of participating schools, spark ideas and make new connections nationally. We can’t wait for the first showcase!

Learn more about You-CAN, the ongoing research study to evaluate You-CAN. You can also find out about how appropriate resources were identified for participating high-school students and their Concussion Councils’ awareness campaigns.

What’s social support and how does it relate to concussion?

A unique aspect of You-CAN is its emphasis on using peer-led concussion education to change behaviours. This is specific to providing a peer with a concussion with social support. For our purposes, social support is an exchange of resources between 2 individuals with the goal of enhancing the well-being of the recipient (Shumaker & Brownell, 1984). There are 3 types of social support: emotional, tangible and informational, as described in Figure 2 (Schaefer et al., 1981).

Best-practice approaches to concussion recovery and rehabilitation involve the potential for restricted activities across many areas of life, including school, sports, social life and family life (McCrory et al., 2017). Although necessary for a safe return to school and sport, these approaches may also lead to social isolation (Karlin, 2011). For children and youth, social isolation can negatively affect health, happiness and quality of life (Karlin, 2011). That’s why social support is so important.

A recent study conducted by our research team within the OAK Concussion Lab at the University of Toronto used semi-structured interviews to explore the topic of social support following concussion in high-school-aged youth. The study’s goal was to better understand what social support means to high school youth, what type of social support they need after a concussion, and the role that peers play in supporting an individual after a concussion (Kita et al., 2020). The youth who took part identified 3 key providers of social support following concussion:

A recent study conducted by our research team within the OAK Concussion Lab at the University of Toronto used semi-structured interviews to explore the topic of social support following concussion in high-school-aged youth. The study’s goal was to better understand what social support means to high school youth, what type of social support they need after a concussion, and the role that peers play in supporting an individual after a concussion (Kita et al., 2020). The youth who took part identified 3 key providers of social support following concussion:

- Close friends who helped to minimize feelings of social isolation through texting and visiting

- Other youth with experience of concussion, who validated the challenges and communicated empathy

- Parents who used their “adult power” to assist with practical challenges like getting accommodations provided at school

Overall, the youth participants wanted their peers to know more about their lived experiences. They proposed solutions that involve educating peers on what it’s like to have a concussion and what supports they need to best help with recovery.

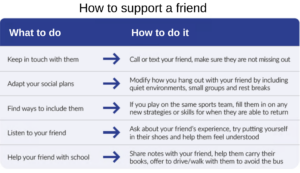

You-CAN attempts to be one of these educational solutions. It can act as a platform to help youth better understand what it’s like to have a concussion. By teaching approaches to social support (see Figure 3 for examples) and encouraging members of the Concussion Councils to include concepts of social support within their annual awareness campaigns, You-CAN enables youth to help each other after a concussion, leading to recovery and positive health outcomes among the youth peers who experience a concussion.

Learn more about the experiences of high-school-aged girls receiving social support during concussion recovery.

You-CAN and sport

To date, You-CAN has been used in Canadian high schools with ongoing research to examine the impact of this novel approach to raising concussion awareness, changing behaviours specific to reporting a concussion to an adult, and providing social support to peers who experience a concussion. There’s great enthusiasm for new approaches to concussion education in the school setting and particularly approaches that consider youth as capable and important leaders. We believe these approaches hold promise for youth in the sport community as well.

Sports teams and organizations may be an important and ideal environment to facilitate peer-led concussion education, particularly since youth who participate in organized sports have significantly higher rates of concussion (Ippolito et al., 2021). Our research has also shown that these youth have room to improve their attitudes about concussion and their intended concussion behaviours, such as reporting a concussion to an adult and providing social support to a peer with a concussion (Ippolito et al., 2021).

Sports teams and organizations may be an important and ideal environment to facilitate peer-led concussion education, particularly since youth who participate in organized sports have significantly higher rates of concussion (Ippolito et al., 2021). Our research has also shown that these youth have room to improve their attitudes about concussion and their intended concussion behaviours, such as reporting a concussion to an adult and providing social support to a peer with a concussion (Ippolito et al., 2021).

Let’s paint this picture for you: Imagine if 1 team in a sport club, league or organization became the Concussion Council and developed and delivered annual concussion awareness campaigns to other teams within their sport organization or league. Perhaps it’s the Bantam hockey team or the U-16 soccer team that becomes their league or association’s Concussion Champions, and all teams, younger and older, look to them for concussion education and support. Players and teams from various sports organizations could come together annually to celebrate their achievements, share ideas and knowledge on concussion to make their team, league and sport safer and more enjoyable. Not only could this approach play a meaningful role in increasing concussion awareness, reporting and social support, but perhaps it could do more. With peers providing concussion education and support through this approach, the information would be better received than if delivered by coaches, parents, healthcare professionals or researchers.

To create a sport-based You-CAN, it will be essential to hear from the youth sport community (such as athletes, coaches, parents and guardians, referees, administrators and others). It will also be vital to create a network and platform that best meets the needs of this community.

A key finding from our current research from You-CAN in school settings is that youth with higher concussion knowledge are more likely to report a concussion to an adult and to provide social support to a peer (Ippolito et al., 2021). Otherwise, youth who participate in sport (such as organized sports, team sports and high-risk sports) are at higher risk of concussion, but also express they’re less likely to report a concussion or support a friend with a concussion. An educational intervention is necessary to improve and change these behaviours in the sport population. Behavioural changes would lead to improved concussion outcomes, happiness and quality of life in youth athletes who’ve sustained a concussion.

How can I increase my concussion knowledge and better support youth athletes?

To best support youth athletes, it’s essential that everyone involved in youth sports is knowledgeable about concussion, including the related signs and symptoms. Additionally, it’s essential for everyone to know what to do when they suspect someone has a concussion. Lastly, you should know your sport’s policies and procedures about removal from play and return to play after a concussion.

To best support youth athletes, it’s essential that everyone involved in youth sports is knowledgeable about concussion, including the related signs and symptoms. Additionally, it’s essential for everyone to know what to do when they suspect someone has a concussion. Lastly, you should know your sport’s policies and procedures about removal from play and return to play after a concussion.

Recently created community resources within the Living Guideline for Diagnosing and Managing Pediatric Concussion provide the following information and direction specific to how you can best support youth athletes in playing the sport they love in a safe and enjoyable way:

- Know about concussion

- It’s essential you’re aware of the signs and symptoms of concussion. Through concussion identification, you can remove an athlete from play and get them the appropriate medical care.

- Concussion signs are how an athlete might look or act after they’re injured. Signs can include getting up slowly after an impact with another player or the ground, holding their head or having difficulty standing, walking or skating.

- Concussion symptoms are how an athlete might feel after they’re injured. Symptoms can include an athlete reporting a headache, nausea, dizziness, difficulty concentrating or changes in emotions.

- It’s essential you’re aware of the signs and symptoms of concussion. Through concussion identification, you can remove an athlete from play and get them the appropriate medical care.

- Know your sports organization’s role in concussion

- Be sure to know if your sport organization has a concussion education program and a concussion policy or protocol. Ensure that everyone involved with your team or within your sport organization is aware of that concussion policy or protocol, and knows what to do if an athlete experiences a concussion. Make sure that these concussion policies or protocols are reviewed and updated regularly. If your sport organization doesn’t have a concussion policy or protocol, then talk to the administration about putting one in place.

- Stay connected and communicate

- To best support a youth athlete after a concussion, it’s a team effort. Communication is essential between the athlete, parents, coaches, teachers and healthcare professionals to be aware of the athlete’s abilities and limitations, and to best support the athlete’s safe return to meaningful activities, including sports.

Conclusion

Youth are strongly influenced by their social networks and often lose out on social participation during concussion recovery. Youth report that having understanding friends who provide them with social support during recovery is very helpful. To best provide this social support, their peers, such as teammates and friends, must have a good knowledge of concussion. You-CAN, a peer-led concussion education intervention, can help provide this knowledge. This way, teammates can support each other when recovering from a concussion. Teammates support each other in many ways, and with the right information and support, concussion recovery should be no different. A sport-based You-CAN, where youth athletes help educate and support other youth athletes with a concussion, could positively influence concussion outcomes and get youth athletes back to what they need, want and love to do.

Next steps

For anyone interested in exploring peer-led concussion education programming in youth sports, please get in touch with us at you.can@utoronto.ca or nick.reed@utoronto.ca.

Recommended resources

You may find these resources helpful as you build your concussion knowledge to best support your youth athletes:

- Living Guideline on Diagnosing and Managing Pediatric Concussion

- Concussion Recognition Tool 5: To help identify concussion in children, adolescents, and adults

- Parachute Concussion Guidelines for Parents & Caregivers

- Concussion Ed – Parachute Concussion Education

- Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport

- CATT: Concussion Information Package for Coaches

For additional resources, check out SIRC’s concussion hub.