One of the biggest stories coming out of the 2018 Winter Olympics was the success of the Norwegian Team, who topped the overall medal count with 39 medals (7.33 medals/million population), compared to Canada’s third-place standing with 29 medals (0.81 medals/million population). In team rooms and in the media, everyone was asking “How did such a small country produce such a dominating performance at these Olympics?

While there are many reasons underlying Norway’s success, an interview with Tore Øvrebø, Director of Elite Sport for the Olympiatoppen, an organization of scientists, trainers and nutritionists who work with Olympic athletes across Norway’s sports federations, drew attention to significant differences in the way sport and physical activity is delivered in Norway compared to other Olympic countries. He describes an ethos of “participation” and focus on developmental outcomes.

Sport should be a human development program…They should learn social skills. Learn to take instructions, and think by themselves. Learn to know what the rules are. Learn why we are doing these things together. So there is a value system going through the [activity] that is actually about developing people. That’s the main goal of sport, to develop people.

In contrast, an ethos of “winning at all costs” has infiltrated youth sport in Canada, degrading the quality of the sport experience resulting in reduced participation (Brenner, 2016) and increased injury (Jayanthi et al., 2013). Building psychological, cognitive, social and emotional skills are largely ignored, yet these are essential ingredients for successful high performance athletes, particularly for our developing athletes (Bailey, 2012). Factors differentiating “super champions” from others include commitment, reaction to challenge, reflection and reward and the role of coaches and significant others (Collins et al., 2016).

This article aims to ignite reflection and dialogue about the ways we develop our younger athletes, particularly in the first three stages of Canada’s Long-Term Athlete Development Pathway (Active Start, FUNdamentals and Learn to Train). It is during these stages that sport can play a role in developing athletes’ executive functions and social and emotional learning skills – the foundations for “human development.” Quality sport can provide outstanding learning environments and opportunities for our young athletes to but this requires deliberate planning and delivery. In the spirit of continuous improvement, this article also aims to cultivate conversations and relationships across the broader sport ecosystem, especially with schools, who make extraordinary contributions toward the development of our youth.

Executive functions – the basic building blocks for success

Success in school and in one’s career requires “creativity, flexibility, self-control and discipline” (Diamond 2016). Underlying these attributes are executive functions (EFs) – a family of mental processes that enable us to plan, focus attention, remember instructions or rules, see things from a different perspective, respond to novel or unpredictable circumstances and juggle multiple tasks successfully (Diamond 2013).

The parts of the brain that develop these EFs are often referred to an air traffic control system. Busy airports have a duty to safely manage arrivals and departures for many airplanes using many runways, all at the same time. Similarly, our brain needs to operate like an air traffic control tower, seeing and managing distractions, establishing priorities for tasks, setting and achieving goals, while controlling impulsive words and actions (Centre on the Developing Child, Harvard University).

These functions are highly interrelated, and the successful application of EFs in real world situations requires them to properly orchestrate their operations with each other. It is generally agreed that there are 3 core functions:

- Working memory governs our ability to retain and manipulate distinct pieces of information over short periods of time.

- Mental flexibility helps us to sustain or shift attention in response to different demands or to apply different rules in different settings.

- Self-control enables us to set priorities and resist impulsive actions or responses. (CDC, Harvard University)

How are executive functions developed?

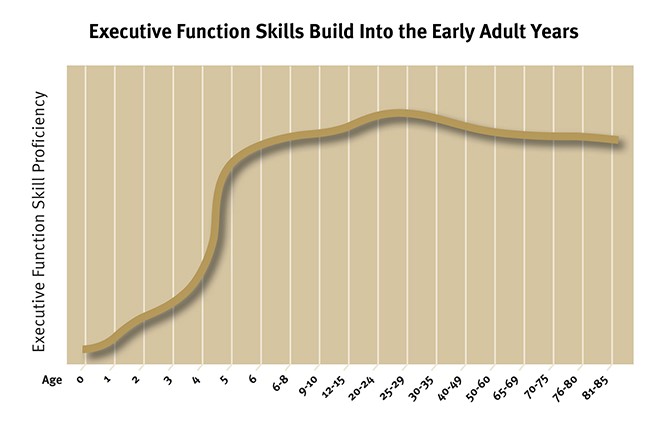

Children are not born with these skills. The figure below shows the results of tests measuring different forms of executive function skills. They begin to develop shortly after birth, with a window of dramatic development between the ages of three to five. Development continues throughout adolescence into early adulthood (CDC, Harvard University).

Parents, guardians and other caring adults are collectively responsible for providing “growth-promoting environments” to enable children to practice and develop these skills where they live, learn and play.

Adults can facilitate the development of a child’s executive function skills by establishing routines, modeling social behavior, and creating and maintaining supportive, reliable relationships. It is also important for children to exercise their developing skills through activities that foster creative play and social connection, teach them how to cope with stress, involve vigorous exercise, and over time, provide opportunities for directing their own actions with decreasing adult supervision. (CDC, Harvard University)

Developing executive functions through sport and physical activity

Diamond (2015) reviews the effects of physical exercise on EFs and identifies preferred types of activity that promote positive impact. These include cognitively-engaging exercise, activities requiring bimanual coordination and eye-hand coordination (e.g. social circus), and activities that require frequently crossing the midline and/or rhythmic movement, such as dance or drumming, particularly when moving with others. Our knowledge about the mechanisms that underlie improved executive functions is growing and includes both structural and functional changes to specific regions of the brain (Cotman et al 2007). While our understanding advances, Diamond (2015) further postulates that executive functions are improved by activities promoting physical fitness, but also those that “(a) train and challenge diverse motor and EF skills, (b) bring joy, pride, and self-confidence, and (c) provide a sense of social belonging (e.g., group or team membership).”

Social and emotional learning – building on the foundation of EFs

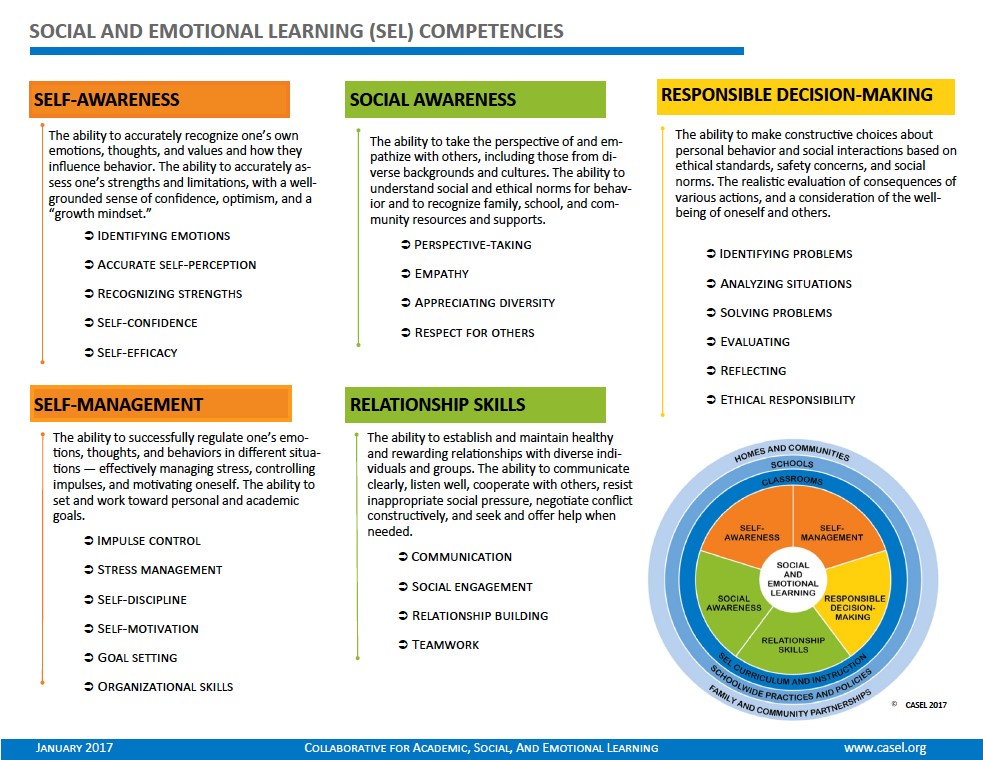

Establishing a foundation of EFs permits the subsequent development of social and emotional learning skills (Diamond 2013). These include self-awareness, self-management, responsible decision-making, relationship skills, and social awareness (see the table below).

“Social and emotional learning is the process through which children and adults acquire and effectively apply the knowledge, attitudes, and skills necessary to understand and manage emotions, set and achieve positive goals, feel and show empathy for others, establish and maintain positive relationships, and make responsible decisions.”

Are program interventions effective?

Since the mid 1990’s, the Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) has been using research, practice and policy to make evidence-based social and emotional learning (SEL) an integral part of education from preschool through high school. These programs have been tested in both the out-of-school and in-school settings.

When implemented as a system-wide approach, research has found statistically significant improvements in cognitive abilities, social cohesion and emotional agility (Durlak et al 2011). Recent studies have demonstrated lasting positive effects around smart decision-making, forming healthy relationships, and goal setting while learning to apply those skills in other areas of their lives (Taylor et al., 2017).

For sustained impact, CASEL identifies three interconnected strategies that need to be tackled:

- Build student competencies and skills through an intentional approach. This should include free standing lessons designed to enhance student social and emotional competence, and the use of teaching practices that promote SEL, such as cooperative learning and project-based learning.

- Design an environment where all students thrive. We know that the environment in which students learn influences their social and emotional development, growth and success. Creating a sense of belonging within safe places accompanied by strong teacher-student relationships are necessary.

- Use organizational strategies to create a climate and culture conducive to SEL, and that develops and supports teacher capacity for advancing SEL.

Developing EFs and SEL through Sport

While much of the work on EFs and SEL has been led by the education sector, we could easily substitute “athlete” for “student” and “coach” for “teacher” and explore the possibilities for community recreation program and sport clubs.

Most coaches would agree that athletes demonstrating self-management, self-respect, respect of others, an emphasis on effort, decision-making and goal setting would be favourable attributes from a competitive sport perspective. Programs that cultivate these values would find their athletes enjoying sport and would likely remain in sport longer. Coaches are essential facilitators in bringing these attributes to life in sport and can provide clear connections to other aspects of the athlete’s life. “The coach must genuinely value the principles of respecting the players, empowering them to have a voice and also emphasizing respect of others and the ability to work independently and put forward effort regardless of who is watching” (Balague & Fink, 2016). Effective implementation of this approach requires: “prioritizing the athlete over wins and losses, emphasizing relationships, taking a holistic approach to developing athletes, and understanding that the model is a ‘way of being’, and not just a set of techniques to be followed” (Balague & Fink, 2016).

There are many different ways that this approach can be integrated into the sport environment; one recommended process is described below:

- A pre-season discussion with athletes about the kind of culture the team wishes to create. Some questions to help guide this discussion include “What are the things that define us?” or “How do we want to be seen by others?” This can also include season goals for individuals as well as the entire team.

- Allow the team to create their own means by which they gather and decide on consequences for players that do not meet the agreed upon standards.

- An awareness talk begins each training session to identify the personal and group goals that target the SEL components. For example, the focus might be on Relationship Skills – during the awareness talk, ask the athletes to describe what this looks like in both sport and non-sport situations. This helps to establish ownership and accountability for the practice session.

- At the end of each training session, there is a rapid check in with players to reflect on their contributions and how this might look in other parts of their life. Using the Relationship Skills from point #3, athletes can identify how they managed these skills during the training session, what did they do or say to promote relationship building or what might they do differently next time.

- While coaches will facilitate the above, they need to honour and respect the athlete voices by supporting their choices. For example, during training, the coach must integrate athlete ideas from the opening awareness talk.

The future has promise

Our youth sport system must find ways to keep children and adolescents engaged in sport. By making sport a more inclusive and appealing choice, more youth will be attracted and retained. Many coaches recognize the importance of an athlete’s social and emotional skillset yet they are uncertain about how to develop, train and progress these skills in their training environments. Implementation of most new ideas is challenging yet can begin with dialogues and learning more about this approach. Recent work by Jean Côté in the area of transformational leadership (Turnnidge, 2017) provides exciting opportunities to explore ways in which coaches can be supported to provide quality sport experiences for their athletes. A focus on developing EFs and SEL skill through their early sporting years may lead to a more developmentally appropriate environment for children and deepen the capability and expertise of our Canadian athlete pool.

Recommended Resources

Video

Check out this 6-minute video from Edutopia for an overview of the “5 keys to social and emotional learning success” – as you watch the video, think of the ways that this approach in your sport environment might make it a better place for your athletes, their parents and coaches.

Education-based websites

Centre on the Developing Child (Harvard University; https://developingchild.harvard.edu/)

Coalition for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL; https://casel.org/)