Highlights

- The “who” is as important as the “what” when sport organizations are planning for data, analytics and evidence-based change related to equity, diversity and inclusion.

- When it comes to race and intersectionality, the power of data practices is its ability to help an organization better understand the realities and experiences of those too often neutralized by the majority.

- Sport practitioners, policymakers and funders who don’t embrace intersectional data strategies carry a heightened risk of their decisions and actions perpetuating a status quo they want to change.

“You can’t manage what you don’t measure” is a popular saying in leadership circles. However, knowing what to measure to inform change is a craft altogether.

To advance equity and inclusion in sport, the “who” of measurement is fundamentally as important as the “what.” Indeed, it’s important to understand the perspectives, realities and lived experiences of the people who experience sport as well as those who are pushed away, left on the sidelines, or chose to opt out. And that understanding has never been more important as sport organizations from coast to coast work to reinvent themselves to be safe, inclusive spaces for all.

This article draws on research findings from the Change the Game research project, by the MLSE Foundation with the University of Toronto. The project aims to clarify the value of embracing data practices concerning race and other identity factors for organizations working to achieve greater equity for youth in sport. At the same time, while calling attention to the systemic and many decision-making risks of not doing so.

Sport, society and social justice

MLSE LaunchPad is a youth Sport for Development (SFD) facility in 1 of Canada’s most socioeconomically and culturally diverse neighbourhoods. The facility is located steps from a university that’s undergoing a renaming exercise, because its namesake was an architect of Canada’s Residential Schools system. Just steps away in another direction, a major thoroughfare’s street name is under review for its namesake having worked to delay abolishing slavery.

Social justice movements actively reflect communities’ and individuals’ lived experiences with institutions. A long overdue, social justice reckoning across society has been sparked, within and beyond sport. That spark comes in the cumulative aftermath of: George Floyd’s murder, the discovery of thousands of unmarked graves of residential school children, and the compounding effect of racist incident after incident.

Organizations across Canada have released many statements, hashtags, and commitments to change. These have come from professional sports to national sport organizations and from SFD programs to municipal, physical activity opportunities for youth. Equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI) roles and committees are commonplace. “Build Back Better” is a popular mantra on social media with implicit acknowledgement that the status quo is no longer acceptable if sport is really going to live up to the promise and potential of sport as a force for good, and for all.

Changing the game: For whom?

If this is truly a watershed moment, where it’s possible to reinvent sport equitably, then the issue before sport providers is how to operationalize such change. How do we dismantle systems of inequality and centre our sport sector around people it’s intended to serve? And crucially, what data exists to guide where to begin and how best to allocate increasingly limited resources? The unfortunate truth to the question of data sources is there isn’t much available. Although data on sport is routinely analyzed through the lenses of age and gender equity, there’s limited (if any) publicly accessible demographic data to support meaningful insights related to race, geography, household income and other intersecting aspects of marginalization.

These are some of the issues that MLSE Foundation explored when launching its Change the Game research program on access, engagement and equity in youth sport. MLSE Foundation collaborated on this research program with Simon Darnell, Ph.D., and the University of Toronto’s Centre for Sport Policy Studies. Amidst slogans and voices calling for change, the fundamental ethos guiding the Change the Game research team was a clear-eyed commitment to understanding the reality of who we’re aiming to change the game for and what practical and concrete success looks like to them.

Informally referred to behind the scenes as a “youth sport census,” nearly 7000 youth, and parents and guardians of youth, responded from across Ontario as a representatively diverse sample for the research program. The sample spanned race, gender, household income level, ability, geography, immigration status and other demographic variables. It became the largest demographic survey of youth sport access and engagement to date in Canada. The survey explored barriers to participation and ideas for building a better and more equitable sport system for the diversity of Ontario’s youth, in the words of youth. A publicly accessible, open-data portal contains a summary report, interactive results dashboard, and an anonymized data set. Stakeholders who are interested in mining the data, may download the data set for their own learning, planning, funding decisions and policymaking.

The rest of this article isn’t meant to repeat the overall findings. Instead, this article will showcase the value of embracing data practices concerning race and other demographic factors, in pursuit of advancing equity and inclusion goals for youth in sport. By making a case for how race and identity-based data can help drive meaningful action toward a more equitable future, let’s pay homage to the great long-form basketball analysts. To do so, we’ll take a deep dive into 2 specific questions from the original Change the Game study and the insights we can draw.

Understanding blind spots

A series of “I” statements formed a 4‑item, Likert-style questionnaire about youth experiences with racism and discrimination in sport. The questionnaire was aligned with MLSE LaunchPad’s MISSION measurement model for youth data collection. Respondents were asked to select whether they strongly disagreed, disagreed, agreed or strongly agreed with each statement.

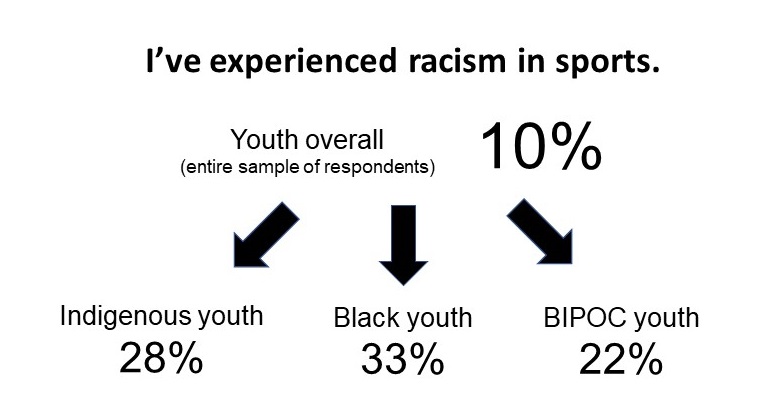

For example, 1 of the statements read: I have experienced racism in sports. Overall, 10% of youth in the study agreed or strongly agreed to having directly experienced racism in sport. Although perhaps meaningful in a dialogue about equity, is 10% on a survey enough for a sport organization, funder or policymaker to meaningfully change course in their decision-making or strategic plan? Hard to say.

Consider now the same statement through the perspective of specific segments of youth in the study.

How does your interpretation of the data change with this additional perspective? If a sport organization is genuinely interested in addressing anti-Black racism or forging right relations with Indigenous communities, does this new story unfolding help to convey a different level of urgency for action?

This is the power of demographic data: enabling one to look in-depth to better understand vital stories and perspectives that are otherwise at risk of being neutralized by the majority.

Now let’s consider a different example.

The fallacy of averages

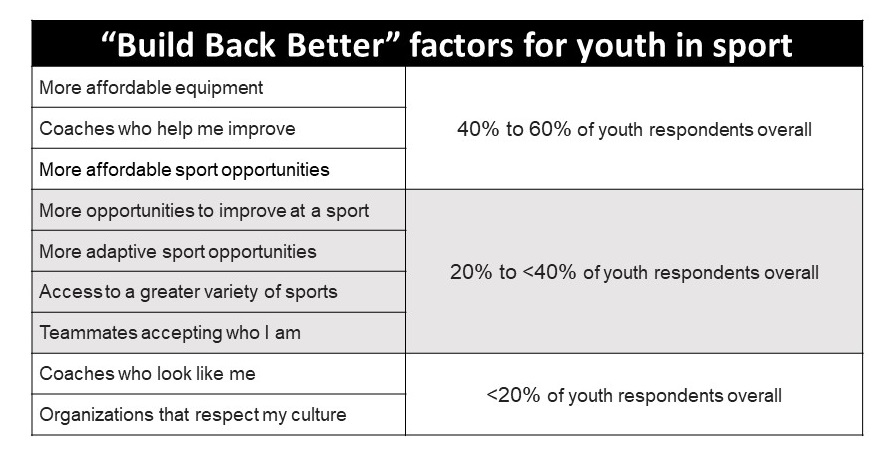

Against the backdrop of “Build Back Better” becoming an increasingly popular slogan or hashtag, youth were asked to shed light in practical terms on what that might look like in their reality. A total of 9 thematic areas (or factors) received greater than 10% of support among youth overall, as follows:

To be clear, each of these 9 factors is an important and sound investment area to improve accessibility and experiences in sport, including the 3 factors that polled the highest.

However, equity isn’t a first-past-the-post concept. In many respects, the opposite is true. To get real about advancing racial equity for youth in sport in an authentic way, one must align their data practices accordingly. Doing so can help by enabling a deeper awareness of the issues and perspectives of constituencies whose relative size may not be large enough to move the overall averages.

With that in mind, let’s explore 2 of the factors in more detail. “Coaches who look like me” and “Organizations that respect my culture” were each called out as important by less than 20% of youth in the overall sample. Do any interesting insights emerge when race-based and Indigenous-identity data lenses or filters are applied?

As it turns out, yes.

Having “coaches who look like me” was identified by approximately 10% of youth overall, the lowest among the 9 factors. However, a closer look affirms this item as having outsized importance to specific demographics within the sample, notably South Asian youth (more than 20%) and Black youth (more than 30%). When reflecting on this 9‑factor list of Build Back Better, how do these additional details inform your own decision-making or perspective on the most critical issues to prioritize addressing?

Exploring who selected “Organizations that respect my culture” through a race-based and Indigenous-identity lens is also interesting, for a different reason.

The distribution pattern is obvious, especially when compared to the Build Back Better table in Figure 3. More than 1 in 5 youth from all 8 of the unique BIPOC categories in this survey called for respect for their culture, even though that rated proportionally much lower in the overall sample of youth.

Decision-making risks

Neither of these examples discredits the importance of any of the other Build Back Better factors cited above. They’re all vital components of a healthy future for youth sport and need attention from providers, policymakers and funders. These examples are provided to reinforce the value of intentionally including demographics in an organization’s data collection plans. Those demographics can shed light more meaningfully on how different experiences and ideas can show up for different segments of the population. If instead of race, the variable of interest had been gender, household income, ability or other intersectional factors of identity, then the results displayed may have told a different story. The core purpose or value proposition is for an organization’s EDI strategy and decision-making process to be informed by the people they intend to serve.

Applying demographic data collection in your organization

Before you can improve an organization’s measurement and evaluation plans, you require some baseline competencies in data management, including privacy, ethics and analysis. Those competencies can help you apply some of the methods and tactics to integrate intersectional demographic lenses to your organization’s plans. Here are tips an organization can consider when getting started. They’re grounded in 4 pillars of transparency, trust, trying it out and talking it out.

- Transparency

If you’re collecting demographic information from staff, coaches, athletes, families or other stakeholders essential to your organization’s success, it’s key to be open and honest with them. For example, openly share why you’re collecting identity-based information, how you’ll handle the information, who will see it, and what you’ll do with the insights you learn. Engaging your core constituencies in these ways can help demonstrate respect, enable meaningful and informed consent to share data, and encourage active partnership on a shared journey to shape a more equitable future.

- Trust

Trust often makes all the difference between complete and incomplete information on a survey or profile page. Whether a respondent has a trusting relationship with the sport organization or its staff will often determine whether that respondent fills out all the fields on their registration or profile forms. Without that trust, they may only complete the required fields. It’s the difference between responding fulsomely to a multiple-choice question on a survey versus just selecting the “prefer not to answer” option. Individual respondents (data contributors) must believe the organization has their back and will use their data to make meaningful improvements. Sometimes this can take time, and it’s OK to be patient.

For example, at the MLSE LaunchPad SFD facility, this is a pattern seen when new members sign up for the first time. Youth, parents and guardians often fill out the minimum required information to get started on attending programs. Then, what and how much they’re willing to share changes over time. Their feedback and sharing practices grow after having built a trusting relationship with staff and the organization. When new members have gained an understanding of how data contributes to understanding and improvements, then that also contributes to enhanced sharing.

- Try (it out)

To echo Courtney Szto, Ph.D., of Queen’s University at the 2021 Anti Racism in Hockey Incubator: Do something! Too many ideas for change get left on the sidelines. Trying to do right typically trumps inaction, even if a concept is imprecise or not fully formed. Even if it’s a small step forward, take a shot. If you don’t achieve your intended outcome, learn from it, regroup, change your approach and try again. Progress can take unusual paths, but there’s tremendous value in letting stakeholders see that you’re actively trying to make a difference.

- Talk (it out)

Data practices don’t come naturally to everyone. If you’re considering a new idea, direction or practice, we encourage you to reach out to someone in the field to help critically assess your approach. If you’re a sport or SFD organization interested in having a sounding board on what an intersectional approach to demographic data collection could look like in your setting, then reach out to a member of the MLSE LaunchPad Research and Evaluation Team.

In closing, sport providers, funders and policymakers want to prioritize meaningful action toward equity, their toolkit to shape the future of sport should include embracing intersectional data collection practices, including race and other equity-related demographic factors. However, keep in mind that there’s potential risk if sport leaders are relying on data featuring top line averages and rankings without an intersectional approach. The data informing their decisions carries a heightened risk of being influenced by the majority and increases the likelihood of actions that perpetuate the very systems they’re supposedly seeking to reshape.

Recommended resources

Centre for Sport Policy Studies, University of Toronto

Indigeniety, Diaspora, Equity and Anti-racism in Sport (IDEAS) Research Lab

About MLSE LaunchPad

MLSE LaunchPad is a 42000 square foot Sport For Development facility in downtown Toronto built and supported by the MLSE Foundation to advance positive developmental outcomes for youth, aged 6 to 29, who face barriers.