Highlights

- In sport, culture can determine a team’s focus and how members communicate and deal with conflict. Culture also establishes norms of acceptable behaviour and directly influences functioning and performance.

- Own the Podium, alongside partners the Canadian Paralympic Committee and Canadian Olympic Committee, identified sport culture as an important performance factor for Canadian athletes to achieve podium success.

- The culture of excellence model outlines strategies for sport organizations to improve their sport’s culture with the goal of achieving enhanced performance outcomes.

- Mental and physical health and well-being, physical safety, psychological safety and self-determination are key person-related factors that contribute to high-performing sport cultures.

An organization’s culture involves the values, attitudes and goals that are shared by a group of people. These values, attitudes and goals influence how the group interacts and operates as its members work toward a common goal.

Within and beyond sport, culture helps to determine a team’s focus, establishes norms of acceptable behaviour and directly influences a team’s functioning and performance. A team’s culture can dictate to team members how to behave, communicate, cooperate and deal with conflict. When clear norms are set, everyone on a team is more likely to follow them.

Own the Podium, Canada’s technical leader in high performance sport, alongside partners the Canadian Paralympic Committee and Canadian Olympic Committee, identified sport culture as an important performance factor for Canadian athletes to achieve podium success. In this article, we define sport culture and describe a “culture of excellence” in high performance sport. We also provide best practices for sport organizations to foster a culture of excellence that enhances the self-determination, safety, health and well-being of their athletes.

Defining sport culture

Research in the fields of organizational and social psychology has played a key role in understanding the relationship between organizational culture and sport culture (Cannon et al., 2006). In the workplace, an organization’s culture can have a significant influence on employee performance, morale, engagement and loyalty, as well as efforts to attract and retain talented employees (Warrick, 2017).

In sport, organizational culture has been identified as having a significant influence on an athlete’s ability to prepare for and perform at major international games (Fletcher & Hanton, 2003; Fletcher & Wagstaff, 2009). Elements of organizational stress, such as personal, team or leadership issues, are a source of strain for athletes that can ultimately affect talent development and how the organization functions as whole (Arnold et al., 2016; Fletcher & Wagstaff, 2009; Henriksen, 2015).

While it’s largely accepted that developing culture is important, until recently, there had been limited work done to define culture in the context of high performance sport in Canada. Furthermore, sport organizations in Canada have identified culture as an area of improvement.

High-performing cultures in Canadian sport

“Good culture is not about a mysterious chemistry; it’s about clarity.” – Daniel Coyle

Recognizing a need to operationally define sport culture, and more specifically, a culture of excellence, Own the Podium is driving a series of research initiatives. Own the Podium collaborated with the Canadian Paralympic Committee to identify several components that contribute to high-performing cultures in Canadian sport:

- Clarity of purpose: Excellence is the guiding principle of all team and organization members.

- Growth mindset: Team and organization members have a willingness to engage in challenging conversations and value the process of self-reflection in the desire to be a curious, lifelong learner.

- Leadership-led: Sport leaders must drive their own culture and engage in self-determined initiatives and strategies that support their drive for excellence.

- Coach-driven: The technical leaders (that is, coach or high performance director) are responsible for driving initiatives and supporting athletes and support staff so that those individuals will share and believe in the assumptions regarding excellence.

- Accountability: Team members are empowered to take ownership and initiative when there’s accountability in their organization’s culture.

- Subculture alignment: Team members within an organization have different roles and responsibilities. Additionally, each team member has sets of different cultural expectations that require alignment and agreement around a shared goal.

Research shows that high-performing cultures are achieved when the beliefs and actions of team members do 3 things (Cruickshank & Collins, 2012):

- Support sustained optimal performance

- Persist across time in the face of variable results, such as wins, losses and ties

- Lead to consistent high performance

When these ideal conditions are met, sport organizations can foster a culture of excellence that supports sustained high performance and personal thriving among its members.

A culture of excellence

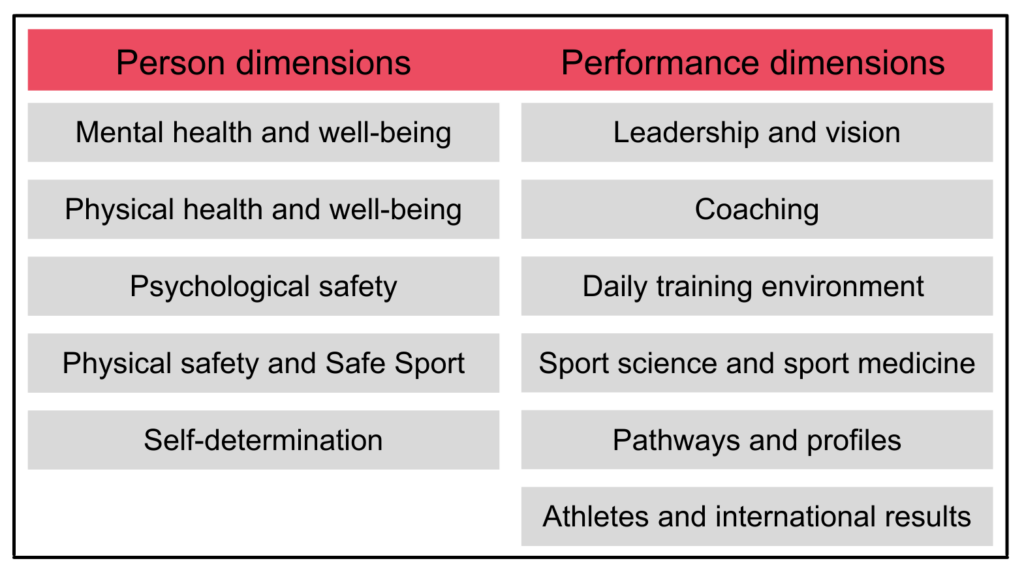

At its foundation, a culture of excellence places a balanced emphasis on both person dimensions and performance dimensions of culture (Paquette, 2020). Person dimensions relate to factors that can influence athlete development and performance. Those interpersonal and intrapersonal factors include relationships, happiness, motivation, fulfillment, safety and wellness. Performance dimensions relate to environmental and strategic factors such as effective coaching, optimal training environments, and the integration of sport science and sport medicine.

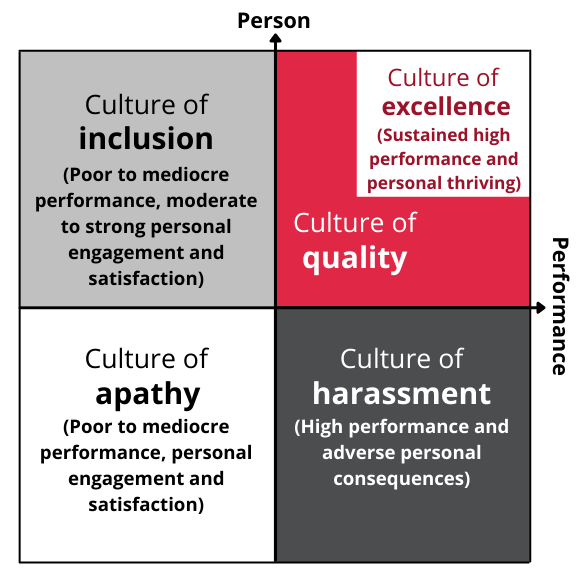

When these 2 dimensions are considered, various sport cultures can be envisioned as a matrix (Paquette, 2020):

An organization can be described as fostering a culture of inclusion when there’s a history of poor to mediocre performance but with moderate to strong personal engagement and satisfaction. Such culture is evident in youth sport contexts, where emphasis isn’t placed on winning, but on participant enjoyment and forming positive social connections.

Organizations are said to cultivate a culture of harassment when there’s strong emphasis on performance outcomes at the expense of personal consequences. For example, a team that discourages athletes from disclosing injury or distress creates a culture that jeopardizes its members’ physical and mental health.

An organization with little consideration for its athletes’ performance or personal outcomes may be described as fostering a culture of apathy. A culture of apathy invites a dysfunctional environment that’s characterized by stress, dissatisfaction and ineffectiveness (Balthazard et al., 2006).

Finally, sport organizations establish a culture of quality when they consider both the person and performance dimensions of culture. When organizations intentionally and consistently work to improve each dimension, they’ll achieve a high-performing culture (culture of excellence) that is sustained long-term.

In recent years, sport has evolved. Sport now adopts a person-centered or athlete-centered approach to decision-making and program delivery, which mirrors changes that happened in education, management and healthcare sectors (Paquette & Trudel, 2018). An athlete-centered approach prioritizes athletes’ holistic development. That prioritization happens by promoting a sense of belonging, as well as giving athletes a role in decision-making and a shared approach to learning (Kidman, 2005). A holistic approach is often stressed as a key issue in successful talent development (Henriksen et al., 2010; Martindale et al., 2005), in which the athletes’ well-being is considered first and foremost. While organizations tend to focus on medal counts and marginal gains in high performance sport, those are only 2 pieces of the puzzle. The person dimensions of sport culture are often underused, but they’re crucial for sustained performance and personal thriving.

Sustained high performance and personal thriving

“The number one way to bring athletes on board and support a culture of excellence is understanding what their personal needs are in their own lives first and then balance them in the sport.” – Robin McKeever, National Team Coach, Para-Nordic

For sport organizations in Canada, it isn’t a new concept to consider the mental and physical well-being of their athletes. However, renewed attention to the person dimensions of culture lets us focus on why we do what we do and gives us a leading edge over competitors. Below, we describe the 5 person dimensions. We also provide key takeaways for each dimension to help sport organizations foster their own culture of excellence.

Dimension #1: Mental health and well-being

Athletes aren’t immune to experiencing psychological distress. In fact, rates of mental illness among athletes are comparable to their non-athlete peers (Rice et al., 2016). Traditionally, “tough” sport cultures emphasized that athletes show mental toughness, which created barriers for those athletes to disclose their psychological distress. That emphasis often leads to stigmatization of psychological distress and associated mental health challenges within sport and athletes perceiving them as signs of weakness (Bissett, 2020). Mental health organizations like the Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport and national initiatives such as Bell Let’s Talk Day are changing the conversation surrounding mental health in Canada. Sport organizations can further support their members’ mental health by ensuring there’s a detailed mental health strategy in place and it’s effectively communicated to all stakeholders.

Key takeaways on mental health and well-being:

- Designate mental health service providers and resources that are available to all members.

- Have a mental health strategy in place and communicate the strategy to all members.

- Support existing discussions and start new ones about mental health and well-being. Such discussions should happen with all stakeholders to normalize and validate fluctuations in and challenges of mental health.

Dimension #2: Physical health and well-being

By its very nature, elite athlete performance is associated with an elevated risk of injury or illness (Engebretsen et al., 2013). A team that encourages athletes to “power through” injury and pain can foster a culture that compels athletes to hide their symptoms, jeopardizing their own physical and mental health. A culture of concealment is driven by athletes’ fear: fear of not being believed, fear of losing, fear of being dropped and fear of being seen as weak or lazy (Wilson et al., 2020). Athletes are more likely to report and seek treatment earlier if their team’s culture openly invites disclosure of pain and injuries, without negative repercussions on sport decisions (for example, team selection). Furthermore, witnessing a trusting relationship between the integrated support team (IST) members and senior athletes can support an open and supportive culture (Wilson et al., 2020).

Key takeaways on physical health and well-being:

- Encourage a culture of openness that promotes early disclosure, discourages secrecy and promotes an athlete-centred approach among integrated support team (IST) members.

- Ensure athlete physical health and well-being are prioritized within the organization, without negative repercussions on sport decisions (for example, team selection).

Dimension #3: Psychological safety

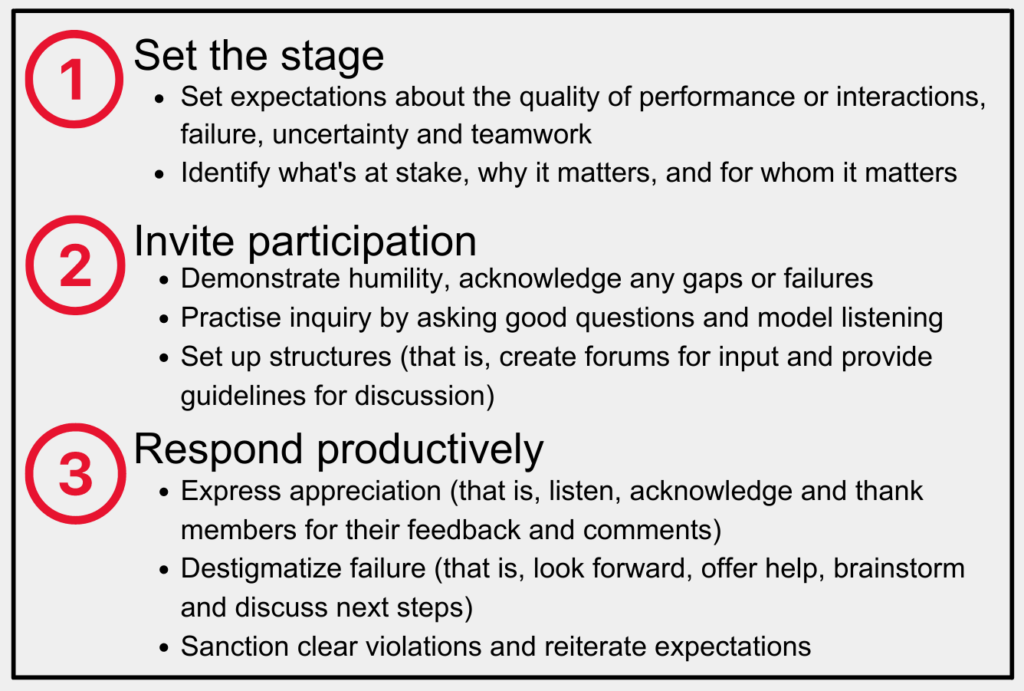

Psychological safety is believing you won’t be punished or humiliated for speaking up about ideas, questions, concerns or mistakes. In psychologically safe environments, there’s a focus on productive discussion to enable early prevention of problems and the accomplishment of shared goals (Edmondson & Lei, 2014). When sport leaders, coaches and other team members nurture a shared sense of “we” and “us,” they’re able to foster a psychologically safe environment, which in turn paves the way for an optimal functioning and healthier team (Fransen et al., 2020). These teams show greater teamwork, improved resilience, enhanced athlete satisfaction with the team’s performance, and an ability to reduce athlete burnout (Fransen et al., 2020). Organizations can help build psychological safety by setting clear expectations, regularly inviting participation and responding productively.

Key takeaways on psychological safety:

- Promote psychological safety among members by intentionally setting clear expectations, inviting participation and responding productively.

- Athletes, coaches, technical leaders and IST members should be able to share information, best practices and feedback with one another in an open, honest and candid way.

Dimension #4: Physical safety and Safe Sport

A goal of the Safe Sport movement is to create sport environments that are accessible, safe, welcoming and inclusive (Kerr, 2021). Safe Sport environments contribute to well-being, are enjoyable and respectful of personal goals, and provide a sense of achievement. As such, Safe Sport environments involve both physical and psychological safety.

A physically safe sport environment minimizes the risk of injury and physical harm for athletes. Strategies to promote physical safety in sport include ensuring that athletes wear proper protective equipment, training and competition environments are up to code, and support personnel are trained and certified in injury prevention and management. Athletes should reasonably expect that the sport environment will protect their physical safety, and that it’s also free from all forms of maltreatment, including abuse, neglect, bullying, harassment and discrimination. Providing a safe and secure sport environment is paramount for athletes’ success during major games (MacIntosh et al., 2020).

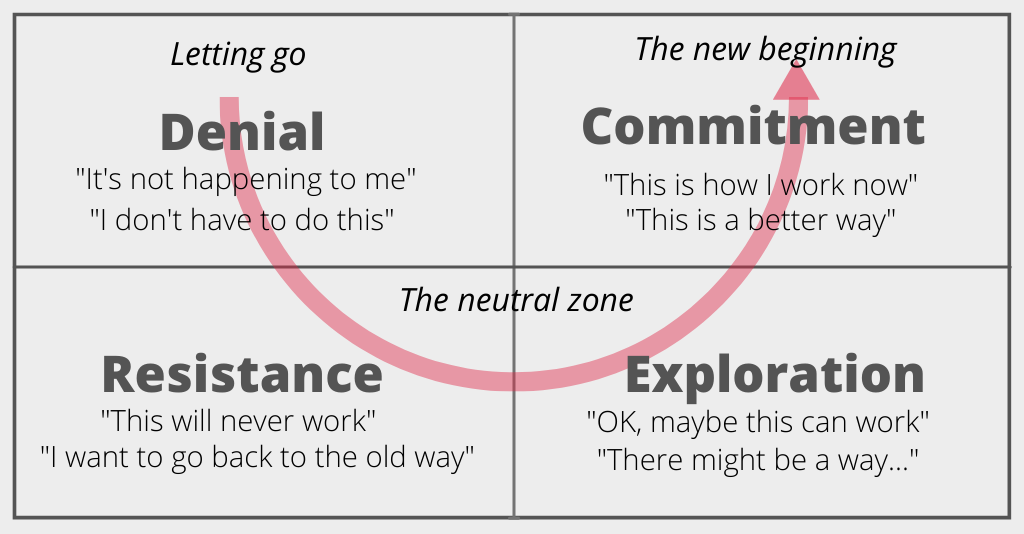

Safe Sport challenges traditional assumptions and practices, such as having coaches share hotel rooms with athletes to save costs or using exercise as punishment. Understanding the process of change and associated emotions (that is, denial, resistance, exploration, commitment) is important for sport leaders to help others adapt better to the Safe Sport journey. While some individuals are already in the commitment stage and have been using Safe Sport practices all along, for others, denial and resistance may exist.

Key takeaways on physical safety and Safe Sport:

- Sport organizations have the duty of care to ensure athletes are physically safe when participating in all sport activities, including the daily training environment, competitions, training camps and travel.

- To promote Safe Sport, sport organizations should ensure that the Code of Conduct and Safe Sport Strategy are available, adhered to and communicated to all members.

- Understanding the process of change and associated emotions (that is, denial, resistance, exploration, commitment) is important for sport leaders to help others adapt better to the Safe Sport journey.

Dimension #5: Self-determination

Self-determination relates to a person’s ability to make choices and manage their own life. To accomplish this, individuals need to feel: in control of their own behaviours and goals (autonomy), capable and effective (competence), and connected with others in their environment (connection) (Deci & Ryan, 2000). When athletes feel autonomous, competent and connected, they are more likely to feel motivated and engaged in their training, which can in turn lead to enhanced performance outcomes.

Coaches, technical leaders and IST providers can foster:

- autonomy by granting ownership, providing options and choice, asking for opinions and offering flexibility.

- competence by emphasizing strengths, providing appropriate structure and guidance, embracing errors and failures, and relaying important feedback.

- connection by prioritizing positive interactions, demonstrating personal care, communicating regularly and reinforcing program performance.

Key takeaways on self-determination:

- When coaches, technical leaders and IST providers provide opportunities for athletes to make autonomous decisions, develop competence and feel connected to others, athletes are more likely to be motivated and engaged in their training.

Final remarks

The culture of excellence model describes a sport culture that builds on Canadian core beliefs and values. In this model, athlete health, safety and well-being are at the forefront. Sport organizations can be inspired to pursue their own culture of excellence through initiatives that support athlete’s health and well-being, safety and self-determination. By balancing the person and performance dimensions of sport culture, organizations will experience benefits. Not only can they experience improved communication, reduced conflict and better functioning teams, but they may also experience higher levels of performance for all team members.

Next steps

A critical next step is to develop an audit tool that will guide sport organizations to assess their high performance culture and identify its strengths and weaknesses. This tool is currently being piloted. The audit tool will be available in the future for Own the Podium targeted sports with high performance programs. A critical component of the audit tool will be the planned engagement with experts to discuss potential culture mitigation or enhancement strategies.

Recommended resources

Canadian Culture of Excellence in High Performance Sport – Position Statement | Own the Podium

Safe Sport Training | Coaching Association of Canada

About Own the Podium

Own the Podium provides the technical leadership for Canadian sports to achieve sustainable and improved podium performances at the Olympic and Paralympic Games through a values-based approach. To learn more about how your sport organization’s culture can optimize the performance of your high performance athletes, contact Own the Podium and ask about the culture of excellence audit tool.