It’s September – a traditional time of transition. This year, because of the COVID-19 pandemic, children are confronting significant change and uncertainty. Children are at elevated risks of negative physical and mental health consequences for several reasons (Chanchlani et al., 2020). First, school, daycare, and community programming closures in March 2020 resulted in potential loss of structure, social interaction, and positive relationships for many. Second, within many families there is financial and employment-related uncertainty. Third, collectively, we are exposed to the persistent fear and anxiety related to the pandemic. Consequences of these risks can include disruption to social-emotional regulation, anxiety, depression, substance abuse, food insecurity, neglect, or maltreatment. Research has revealed that the mental health of children has declined since the pandemic began (Statistics Canada, 2020).

The collective trauma that children may carry with them as they return to school and community programs, coupled with significant change and uncertainty, can be overwhelming during critical stages of their development. Given these circumstances, there is a need for program staff, coaches, and teachers to integrate strategies to meet children where they are and accommodate their unique needs.

The Impact of Trauma

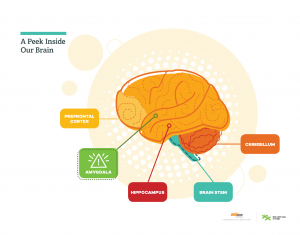

Trauma is defined as significant one-time, multiple, repeated or enduring events that disrupt children’s regulatory systems (e.g., family dysfunction, maltreatment and abuse, community violence; CAMH, 2020). The severity of traumatic impact can vary from child to child, depending on each child’s threshold for handling potential stressors. Stressors can range from loud noises to physical contact, to adjusting to new situations – such as the requirements of public health protocols. When exposed to a potential stressor, the part of the brain that responds to fear (amygdala) activates and overrides other parts of the brain from functioning effectively (See Figure 1: A Peek Inside Our Brain). Some children may show a fight (show aggression), flight (run away), or freeze response (unable to respond). They may also experience physiological responses, such as increased heartrate or breathing. This fear response may last some time before the “thinking brain” (prefrontal cortex) re-activates, which is responsible for planning, decision-making, and putting thoughts into words. When children experience trauma, the experience may be so overwhelming and/or so frequent that it disrupts the typical stress response system. When this happens, it can take much longer for the dysregulated child to return to stability and re-activate their thinking brain, leaving them stuck in a fear state. Researchers have suggested that physical activity can be used as an effective means to restore bodily regulation and feelings of control for those exposed to trauma (Massey & Williams, 2020).

Trauma-sensitive Design

A trauma-sensitive play experience can support healing for children affected by trauma (D’Andrea et al., 2013). In trauma-sensitive play, practitioners create a supportive environment by harnessing social and environmental protective factors that can contribute to children’s resilience. Below are three trauma-sensitive strategies for practitioners to integrate into their programming:

1. Foster a sense of safety and engagement in caring relationships. Establishing safety and consistent relationships are the foundational pieces to any trauma-sensitive design. Children need a place to feel safe when their worlds seem chaotic. Frequent, caring, and nurturing relationships with adults are crucial for their healing from trauma. Practitioners should meet children with warmth and patience and check-in to see how they are as people as opposed to program participants. Children need to feel that they can approach their practitioners for support whenever they feel overwhelmed – and not feel as if their uncontrollable behaviours or means of coping are a burden for staff.

2. Build body awareness and physical competency. Children may find it difficult to understand their body’s reactions in a dysregulated state. They may feel a lack of control and that their bodies no longer belong to them. Engaging in physical activity releases endorphins and other chemicals that can counter the effects of stressors, and building body awareness and physical competency can help children take back control over their bodies, and facilitate their post-traumatic growth (Massey & Williams, 2020).

Practitioners can promote body awareness by teaching children to monitor their heart rate at active and resting states (e.g., checking their own pulse) or rating their energy levels at different points of the program (e.g., on a 1-5 scale, or by giving thumbs-up/down/sideways).This strategy can help children be more aware of how their body reacts in stress (e.g., rapid heartrate, quicker breathing) and how they can restore themselves to a resting state (e.g., practicing breathing techniques). Practitioners can also offer an alternative space outside the program area (See Figure 2: The Zone) where children can retreat if they feel overwhelmed, returning to play when they are ready. Building physical competency is also important in healing trauma – children need to feel strong and skilled in their own bodies. Engagement in repetitive, rhythmic activities can promote skill-building while also helping children practice self-regulation.

3. Facilitate engaging activities that help children stay present. Adverse experiences leave a powerful mark that may force a child to relive these experiences involuntarily in their memories. Play can offer an opportunity for children to leave these experiences at the door. Practitioners can help children stay in the moment by maximizing activity using group drills, cooperative or small-sided games. and in-depth discussion with those on the sidelines during game-time. Avoid disengaging activities such as laps, lines, or lectures.

A Trauma-sensitive Lens

Along with using a trauma-sensitive design to help support the diverse needs of children, practitioners should also be equipped with a trauma-sensitive lens to effectively intervene with individual children in times of dysregulation. Children’s experiences over the last several months will shape their behaviours and ways they express themselves. Without a trauma-sensitive lens, practitioners may respond to a child who is acting out by attempting to manage their behaviours (e.g., “stop that,” “sit and listen,” “come back here”) or thoughts (e.g., “what’s wrong with you?” or “why can’t you do this?”). Using a trauma-sensitive lens, practitioners can recognize that a dysregulated child may be acting out due to a lack of skill in regulating their thoughts, emotions, and behaviours, rather than a lack of will to respond in prosocial ways.

When using a trauma-sensitive lens, practitioners prioritize supporting the child to return to a stabilized state. The SEPRR approach (Edgework Consulting, 2020) provides guidance to work one-on-one with a child struggling to regulate their emotions during play:

- Stabilize: Support the child in managing their fear response. Help the child slow down their reaction; encourage them to breathe deeply, check their own pulse, and transition to a resting state. Suggest engaging in an alternate activity together (e.g. playing catch, kicking a ball, taking a walk, or another rhythmic activity) to help the child naturally self-regulate through practice of a rhythmic, repetitive task.

- Explore: While engaging the child in the above physical activity, try to understand what is going on in that moment for the child. Ask the child what happened during play, and how the child is feeling. Retuning to a regulated state may take time – be patient.

- Plan: Work together on options for what the child can do in this situation and similar future situations. Explore or propose alternative activities the child can choose when feeling triggered.

- Rejoin: When the child is ready, support them in returning to the activity at their own pace. Spend time with the child through this transition and refrain from pressuring the child to return.

- Restore: Help the child experience the powerful and enabling feeling of having worked through their dysregulated state. Invite the child to pause and consider what they did to work through this challenging situation. Take a moment to remind them that the relationship with you is intact and even stronger having gone through this together.

Concluding Remarks

Despite traumatic exposure, children are capable of remarkable strength. The very idea that children will get out of bed, ready their backpacks, and step foot into school this September is a marker of their resilience. Leveraging protective factors by integrating trauma-sensitive design and using a trauma-sensitive lens, can help practitioners meet and support the diverse needs that children may carry with them as they return to play. Whether you are on the soccer field, at the recreation centre, or in a physical education class, adopting trauma-sensitive practices ensures a more holistic approach to supporting children’s return to play and school, and their continued thriving.

Recommended Resources

For more strategies to incorporate trauma-sensitive design into play, review the resources available from these sources below:

Bartlett, J. D., & Steber, K. (2019). How to implement trauma-informed care to build resilience to childhood trauma. Child Trends. https://www.childtrends.org/publications/how-to-implement-trauma-informed-care-to-build-resilience-to-childhood-trauma

Bergholz, L., Stafford, E., & D’Andrea, W. (2016). Creating trauma-informed sports programming for traumatized youth: Core principles for an adjunctive therapeutic approach. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy, 15(3), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/15289168.2016.1211836

Edgework Consulting (2020). Promoting Emotional Regulation https://704b5801-34ca-499b-b110-736a60d31bc2.filesusr.com/ugd/7b1a5d_d2d194aa2fc542668081d57360c3517f.pdf

Edgework Consulting. (2020). Sport for healing. https://www.edgework-sportforhealing.com/

Edgework Consulting (2020). Stepping in During Times of Dysregulation (SEPRR Approach) https://704b5801-34ca-499b-b110-736a60d31bc2.filesusr.com/ugd/7b1a5d_fa68217a3df943389439825a9acf885f.pdf

Girls Inc. (2020). Trauma sensitivity and support at Girls Inc. https://girlsinc.org/trauma-support-resources/

Play Like a Champion Today. (2020). For coaches: How to be trauma sensitive & responsive in your coaching. https://www.playlikeachampion.org/trauma

SAMHSA. (2014). SAMHSA’s Concept of Trauma and Guidance for a Trauma-Informed Approach. HHS Publication, July, 27. https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/d7/priv/sma14-4884.pdf

Swiss Academy for Development (2020). Manual on Trauma-Informed Interventions Based on Sport and Play. https://sad.ch/en/news-media/publications/manual-on-trauma-informed-interventions-based-on-sport-and-play/

Up2Us Sports. (2020). Resources. https://www.up2us.org/resources-1