An athlete’s ability to cope with stress is crucial for performing well in competition. Many stressors can arise for athletes, including training demands, pressure to do well, conceding points, and discomfort.

Most of the stress that athletes experience during competition stems from unexpected stressors. In fact, research shows that between 69% and 92% of stressors experienced by athletes weren’t anticipated prior to competition (Dugdale et al., 2002; Holt et al., 2007).

Compared to expected stressors (stressors that an athlete has planned or prepared for), unexpected stressors often result in athletes feeling more stressed (Dugdale et al., 2002). Unexpected stressors also result in athletes showing poorer coping efforts and stronger emotional responses (Devonport et al., 2013). Collectively, this inability to manage unexpected events surrounding competition can negatively affect athlete performance (Gould et al., 1999).

Unexpected stressors happen often and are more challenging to manage than expected stressors. However, they can be managed. One way to manage them is by expecting them. To help reduce the frequency and impact of unexpected stressors, we describe and provide examples of common unexpected stressors during competition. Then we offer 4 research-informed recommendations for coaches and practitioners to help athletes expect and prepare for those stressors.

Unexpected stressors happen often and are more challenging to manage than expected stressors. However, they can be managed. One way to manage them is by expecting them. To help reduce the frequency and impact of unexpected stressors, we describe and provide examples of common unexpected stressors during competition. Then we offer 4 research-informed recommendations for coaches and practitioners to help athletes expect and prepare for those stressors.

What’s an unexpected stressor?

An unexpected stressor is an occurrence that athletes didn’t foresee or anticipate (Dugdale et al., 2002). When asked about common but unexpected stressors, athletes list physical ailments (such as injury or discomfort), competition outcomes (such as conceding points), and in-competition interactions (such as heckling by spectator).

These occurrences, though not ideal, aren’t rare. Rather, many stressors reported by athletes as unexpected are within their scope to be prepared for. For example, conceding points is unlikely to be a complete surprise. It’s probable that an athlete experienced a similar stressor in past competitions and could recognize that conceding points is a possibility. However, athletes still perceive these events as unexpected. They have the potential to negatively affect their coping, stress, and performance.

Recommendation 1: Acknowledge that deviations can and will happen

Athletes aren’t typically prepared to deviate from competition-related norms, expectations, and personal hopes (Thatcher & Day, 2008). It’s crucial to encourage athletes to consider and prepare for the reasonable possibility that there may be differences in what they think will happen, and what actually happens. For example, there may be times during competition when something doesn’t go the athlete’s way, such as an unfavourable referee call, conceding points, or errors. Alternatively, there may be instances that deviate from competition norms, like changes to the event schedule or unusual crowd behaviour. Preparing athletes for the possibility that the competition won’t go exactly as planned may reduce the impact of such deviations if they happen.

Recommendation 2: Go back to the basics in high-stakes competitions

In high-stakes competition, such as a championship game, regular competition stressors are just as likely to happen. For example, points may still be conceded and referees may still make unfavourable calls. Although one can’t anticipate and prepare for every situation in sport, it may benefit athletes to be realistic about considering possible stressors that are undesired or not typical in competition, but still common enough that athletes should prepare for them. Coaches and practitioners can help athletes recognize this possibility and support them in identifying and preparing for such stressors.

Recommendation 3: Engage in comprehensive planning

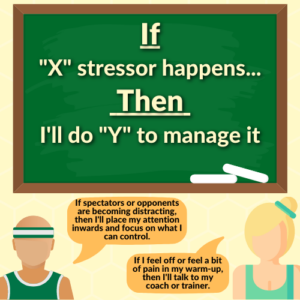

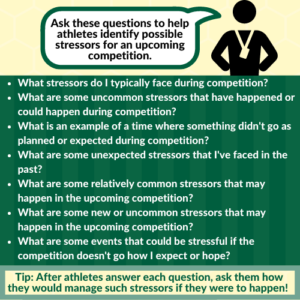

Working collaboratively with athletes to anticipate stressors can provide structure and support to help athletes consider possible scenarios for upcoming competitions. One way to do this is by using “what if” scenarios (Bull et al., 1996; Thatcher & Day, 2008).

When working through a “what if” scenario, an athlete is prompted to consider the events that might happen and contemplate how they might respond to such events (Bull et al., 1996). “What if” plans should include “typical” competition stressors, such as nerves and spectators, stressors that don’t align with one’s expectations and hopes, such as conceding points and negative competition outcomes, and stressors that are unfamiliar or not typical of competition, such as potential discomfort and new venues. Making an intentional effort to identify potential stressors and how to manage them is the key to comprehensive planning.

Recommendation 4: Recognize similarities with others

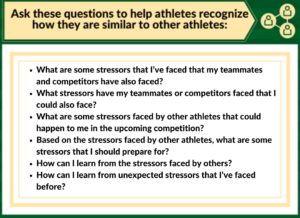

Some athletes have reported perceiving stressors as unexpected, not because they were unfamiliar with the stressor, but because they didn’t expect such stressors to happen at their competition (Gould et al., 1991, as cited in Dugdale et al., 2002). We should encourage athletes that when anticipating stressors prior to competition to recognize how other athletes (such as teammates and opponents) are like them. This promotes the understanding that the athletes aren’t immune to experiencing stressors. One way to do this is to ask athletes to “list ways in which other people experience similar events” (Mosewich et al., 2013, p. 519).

Coaches and practitioners shouldn’t encourage athletes to be mindful only about stressors that they’ve experienced or could experience. They should also encourage athletes to learn from past stressors faced by teammates, opponents and other athletes.

Moving forward: Expected and not a surprise

Given the challenges associated with unexpected stressors and how often they happen, it’s important for athletes to expect and prepare for stressors during competition. Coaches and sport psychology practitioners can help athletes do this. Unexpected stressors aren’t always new or difficult to anticipate, so athletes don’t anticipate the need to manage them. Perhaps attention needs to be given to the “unanticipated.” Unexpected events will inevitably happen in sport, but coaches and practitioners can support athletes in preparing to anticipate and overcome the many stressors athletes may face in sport.

If you’re interested in learning more about the perception and management of unexpected stressors, please contact bjsereda@ualberta.ca.