Highlights

- Both indoor and outdoor sports are vulnerable to the effects of climate change, from heat waves and diminishing amounts of snow to disruptions in supply chains.

- As a first step to prepare for and adapt to the effects of climate change, engage board members and staff in intentional discussions about the climate hazards that may affect your sport.

- To increase adaptive capacity, start with the soft infrastructure items (e.g., writing new policies, building awareness about climate risks among staff) and work your way up to the costlier ‘hard’ infrastructure development (e.g., infrastructural upgrades).

- Sport organizations can use the Sport for Climate Action Framework as a tool to orient thinking around mitigating climate change through climate action and advocacy.

According to the United Nations, climate change is the defining issue of our time, and we are at a defining moment. In Canada, a national climate emergency was declared by the House of Commons based on the revelation in a 2019 federal climate report that our country is warming roughly twice as fast as others. While infrastructure, livelihoods, and health are top of mind with regard to climate change, all sectors will be impacted.

Sport is not immune to the impacts of climate change. In January 2020, the world watched in horror as Australia’s bushfires raged and athletes at the Australian Open collapsed from heat exhaustion under orange skies, their shoes melting onto the searing court. In Europe, unprecedented heat waves loomed over the 2019 Women’s FIFA World Cup. Here in Canada, forest fires in the west have compromised air quality, keeping many athletes indoors. And of course, winter is getting shorter and the amount of snow has been diminishing since the mid-twentieth century. Climate change isn’t going away; it’s only getting worse.

The purpose of this article is to introduce climate change as an important consideration for strategic sport management for the future. The first section discusses the risks, and how sports organizations can prepare and adapt to climate change to minimize losses and disruptions. In the second section, the Sport for Climate Action Framework is introduced as a tool to orient thinking around mitigating climate change through climate action and advocacy.

Coping with climate change

Vulnerability to climate change is the degree to which an entity—such as a person, an organization, a building, or a community—is at risk of experiencing negative outcomes from climate change, such as warmer weather, droughts, fires, floods, and storms (IPCC, 2018).

The United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR, 2004) provides a framework to assess vulnerability based on three key factors:

- Exposure – how likely is X to happen?

- Sensitivity – how bad would it be if X happened?

- Adaptive capacity – how ready is the entity to cope with X, with minimal disruption or losses?

Some sports are more vulnerable to climate change than others. Outdoor sports and those heavily reliant on natural resources are most at risk of experiencing setbacks due to climate change. This includes sports such as swimming or indoor hockey for their heavy reliance on water. Winter sports are on particularly thin ice (pun intended). For example, research from the University of Waterloo suggests all ski resorts in Ontario and some in Quebec could be faced with winters too short to remain economically viable within 50-60 years if current emissions trends are not curbed (Scott, Steiger, Knowles & Young, 2015). Likewise, research on outdoor skating in Toronto revealed that the number of skateable days has fallen by 25% since the late 1950s (Malik, McLeman, Robertson & Lawrence, 2020) and is projected to fall another 33% by the year 2090 (Robertson, McLeman & Lawrence, 2015).

For summer sports, heat waves and air quality are the key challenges (more on that below). While somewhat insulated, indoor sports can also be vulnerable to climate change. For example, supply chains can be compromised or slowed; travel to-and-from practices and games can be impacted; and poor air quality can seep into indoor areas, rendering them unsafe.

Identifying the risks

The first and most important step in adapting to climate change is to identify and learn about the potential hazards. This process should be intentional and ongoing, starting at the top. Climate hazards should be regularly discussed by the board of directors and staff should be encouraged to read up about what is currently happening (heat waves, storms, wildfires, etc.) and what will likely change in future due to climate change. Together, an informed leadership and staff team can engage in meaningful climate adaptation efforts. Many free resources exist to support this type of fact-finding and future thinking: perusing the Climate Atlas of Canada is a good place to start.

Once the climate hazards that may affect your sport have been identified, organizations can take action to proactively increase adaptive capacity.

Opportunities to adapt

Sport leaders cannot control climate change, but they can control organizations’ adaptive capacity. The good news is that most adaptive measures are relatively simple and inexpensive. Start with the soft infrastructure items (e.g., writing new policies, building awareness about climate risks among staff), and work your way up to the costlier ‘hard’ infrastructure development (e.g., infrastructural upgrades).

Developing weather policies

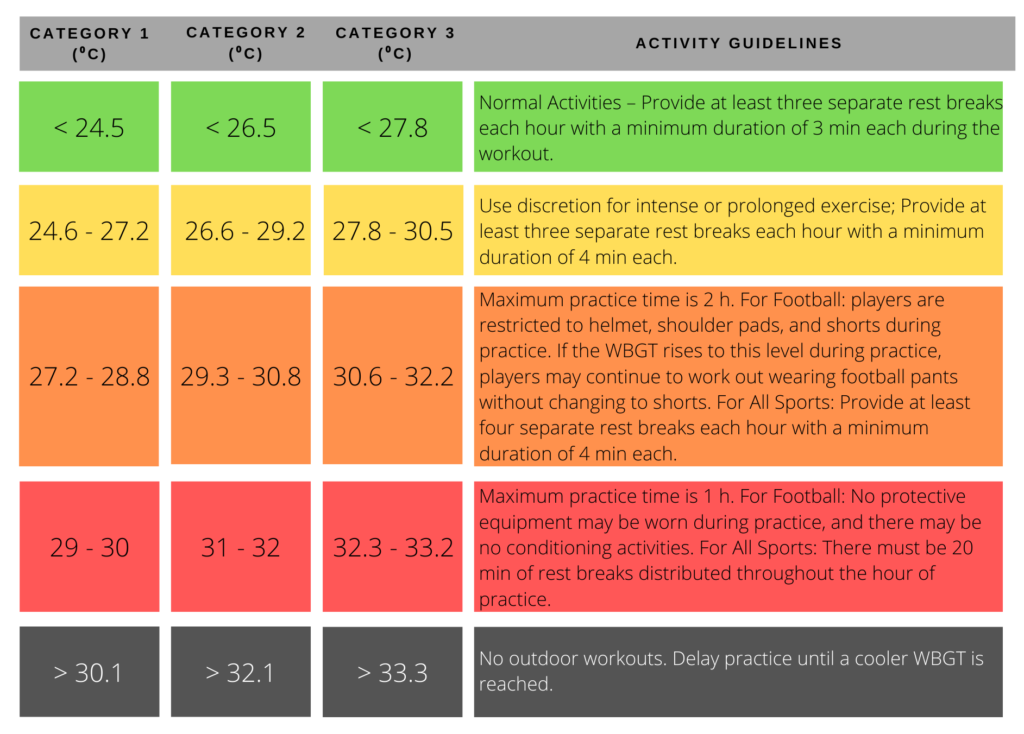

Weather policies, such as heat policies, lightning policies, and air quality policies, codify safe conditions of play. Typically, these include thresholds for what is considered safe, and a pre-determined action at each threshold. The specifics of these policies will differ based on the sport and available facilities. For instance, at X temperature, an extra water break is added, or at X air quality index rating, practices and games must be moved indoors or postponed. Table 1 offers the Korey Stringer Institute’s latest heat-related guidance for outdoor sports. Already, most sport organizations in Canada have a lightning policy that calls for delaying play when lightning strikes nearby.

Weather policies allow coaches and other decision-makers to act quickly when necessary, alleviating any on-the-spot stress of decision-making or deciding on a best course of action. If the polices are already there, the adaptations can be quick when the hazards arise.

Table 1: Suggested heat policy guidelines for football and outdoor sports (Korey Stringer Institute, 2018).

The sport of soccer is ahead of the curve on this: Major League Soccer is the only major sport league to have a heat policy. In Canada, Alberta Soccer has an air quality policy which requires officials and coaches to reduce the intensity of play, reduce the duration of practices, provide more rest breaks, or reschedule altogether, depending on the level of pollution in the air.

Strategic partnerships

Space-sharing partnerships can provide organizations with access to alternative facilities to reduce the impact of inclement weather. During focus groups I conducted with Australian and British sport leaders in the fall of 2020, a few possible suggestions emerged. For example, a tennis club manager proposed partnering with a local basketball club to share space so tennis players could use the gym to do an indoor workout when weather conditions were poor, and basketball players could get outside to cross-train or use the courts for group workouts.

Resource- and information-sharing partnerships are another option for adaptation. For example, sport organizations could co-invest in weather radar technologies that would provide managers and coaches more information than what’s available on the weather channel. Alternatively, sport organizations could share the costs of a consultation with a climate expert or sport scientist to help develop weather policies.

There are also several groups across the country that support sport leaders in understanding and responding to climate change. Most notably, the Canadian alliance of signatories to the Sport for Climate Action Framework support regular meetings and best-practice sharing amongst organizations such as the Canada Games, the Canadian Olympic Committee, the World Masters Athletics event, and others. The alliance also convenes researchers working in the climate and sport space to help guide sustainability strategies and climate adaptation efforts. Community, provincial/territorial and national sport organizations can also leverage their positions as influencers and information clearinghouses to distribute best-practice guidance.

Follow municipal leadership

Most municipalities across Canada, from Victoria to Toronto to St. John’s, have a climate adaptation plan that outlines the steps cities are taking now to prevent climate problems in future. These include, for example, adding bike lanes, electrifying public transit, sourcing green energy, and preparing storm drains for heavier rainfall. Those municipalities that do not have a plan default to their provincial/territorial plans. These plans are often complemented by funding and subsidy opportunities. For example, Montreal is committed to increasing green space and sun shade, so Montreal-based sport organizations might apply for municipal funding to add shading (e.g. trees, partially-covered shelters) to their outdoor fields as a sun and heat-safety strategy.

Build in flexibility for multi-use spaces

In the face of climate change, creativity and flexibility will be paramount. Be ready to pivot from outdoor training sessions to indoor training sessions, saving time and headaches when the weather does not cooperate. If you are a winter sport, or a sport with stricter climate demands, develop your facility’s summer activities. Ski resorts across the country are leading innovation in this area, but more can be done. Turn outdoor arena space into a summer ball hockey facility, or promote downhill ski resorts as trail running and hiking destinations.

Infrastructure and equipment upgrades

Air handlers and air purifying systems can keep wildfire smoke in the building to a minimum, but they are expensive. Adding shaded areas to an outdoor sports facility (from roofs on baseball dugouts to new trees along the edges of fields) can go a long way in protecting athletes and spectators from heat-related illnesses. Adding natural ditches and water drainage on the site can alleviate the risks of flooding. In the most extreme case, enclosing an outdoor facility can provide for climate-controlled conditions indoors and limits exposure to the elements.

The Sport for Climate Action Framework

Coping with climate change is one thing. Mitigating future change is another.

Sport has significant potential to serve as a vehicle for climate action. Many reputable organizations agree (the United Nations, the Obama Administration, the International Olympic Committee). This can be done in two ways: by reducing the environmental footprint of the sport sector, and by increasing the sector’s “brainprint”—the amount of attention and awareness the sector draws to climate issues and sustainability.

These two overarching goals are well represented in the Sport for Climate Action Framework, the UN’s latest effort to drive climate action in sport. The Framework includes five principles to guide this effort:

Principle 1: Undertaking systematic efforts to promote greater environmental responsibility

A systematic effort to promote greater environmental responsibility must infiltrate every level of the organization from the c-suite to the volunteers. Complement aspirational long-term goals (e.g., Seattle Kraken’s climate pledge arena is aiming for carbon neutrality; so is the Paris 2024 Olympics) with short-term, actionable goals that can provide early wins (e.g., reducing paper use, implementing recycling and composting programs). In the same way sports organizations envision the ‘Road to Rio’ or to another major event, with several small but important steps on route to a bigger goal, a ‘Road to Zero’ can be envisioned.

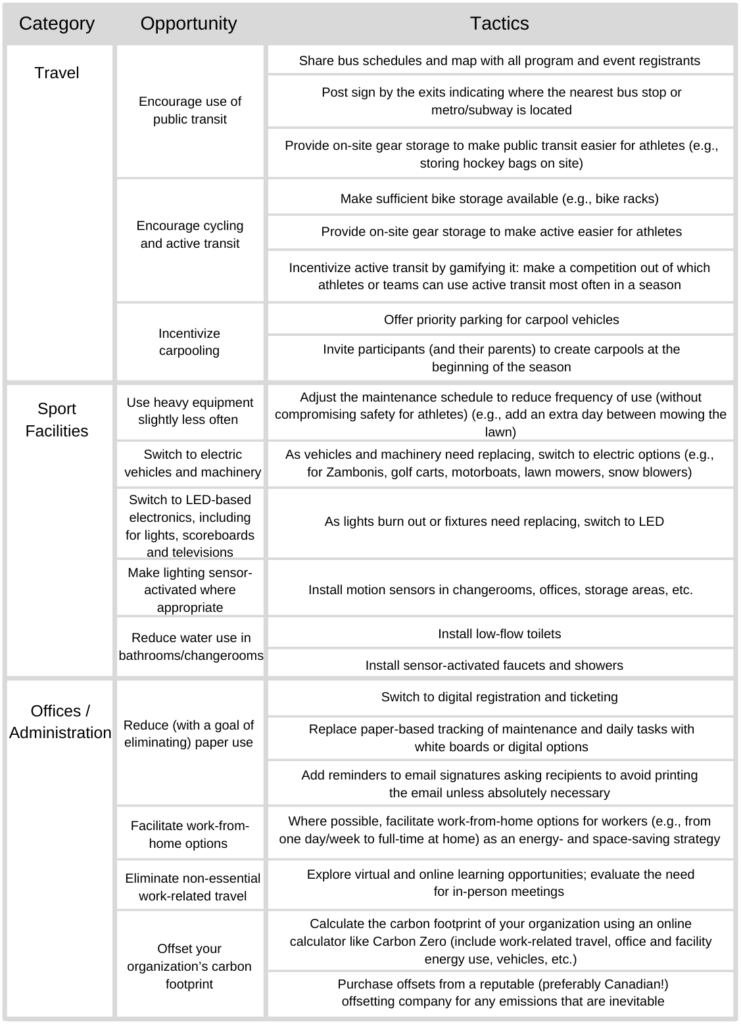

Principle 2: Reduce overall climate impact

The biggest challenge to reduce the overall climate impact of the sport sector is reducing emissions associated with travel to-and-from practices, games, and competitions. Travel represents upwards of 80% of overall emissions in sport, at every level from grassroots clubs to the elite professional leagues (Dolf & Teehan, 2015; Dolf, 2017; Wesström, 2016). Research suggests active sport participants have an average annual carbon footprint of 844 kg of carbon dioxide-equivalent emission (Wicker, 2019). These emissions can be addressed by encouraging athlete and participants to take public transit or cycle, or by changing competition schedules to limit long-distance travel (e.g., by holding the round-robin rounds of provincial and national competitions regionally, and having only the top four teams travel for the semi-finals and finals). Table 2 provides strategies for sport facilities to reduce their climate impact.

Table 2: Menu of Opportunities to Reduce Overall Carbon Footprint

Principle 3: Educate for climate action

Publicly declare your organization or team’s commitment to climate action and environmental stewardship. Explain what actions are being taken to reduce the organization’s footprint, and the goals for future action. Invite participants and fans to be part of the greening process by sharing regular updates and identifying ways for them to support the process. For example, the Banff Marathon, dubbed the “World’s Greenest Marathon,” has a webpage dedicated to sharing their sustainability efforts, and showcases their efforts at the event. Scotiabank Arena in Toronto has a similar page on their website, describing their strategies to reduce the facility’s environmental footprint.

Principle 4: Promoting sustainable and responsible consumption

This principle is linked to education and reducing overall impact. Consumption by sport organizations includes all procurement, sourcing, and staffing. Decision-makers can consider the following hierarchy of sustainable sourcing practices (from most to least effective):

- RETHINK how you view natural resources and our relationship to the natural environment. Apply the “leave no trace” philosophy. If a material or item will have a damaging impact, such as a harmful pesticide to maintain a field, or single-use plastic cups for water, consider using less of the product or choosing an alternative.

- REFUSE to accept or support companies, events, products, and ideas that harm the natural environment or the people who inhabit it (this includes refusing to support racism, sexism, homophobia and transphobia, and other harmful belief and behavior systems).

- REMOVE items you don’t need. Declutter. Simplify. For instance, can extra swag or brochures be cut from next year’s procurement plan?

- REDUCE the amount you order, of everything. Do you need ten soccer balls, or will six suffice? Consider strategies to reduce the use of office supplies.

- REPLACE suppliers and partners that do not meet your organization’s standards for sustainability. Often, when suppliers, sponsors, or partners are presented with the opportunity to improve something to align more closely with your sustainable values, they will. For example, ask suppliers to use less packaging (no single-wrapped t-shirts or pieces of equipment), or encourage sponsors to share and promote their sustainability work through the sponsorship.

- REUSE whatever you can. Last year’s leftover volunteer t-shirts will work just fine this year (pro tip: avoid including the year on event materials for recurring events, so signage, t-shirts, and marketing materials can be reused).

- RECYCLE paper, electronics, plastics, metals, and whatever your city or town can accept. Put up signs around your facility to encourage visitors and staff to follow your lead. Where possible, implement composting.!

- RETURN anything you can. Choose to rent or borrow, rather than buying equipment that will sit idle for long periods of time.

Consumption by sport participants and spectators includes the way they engage with and consume your product. Make it easy for them to be sustainable in their sport participation (e.g., go all-digital with communications and forms) and invite them to share their at-home sustainable practices with the team or group!

Principle 5: Advocate for climate action through communication

This is related to climate education but demands one extra step: advocacy. It is not enough to wish and hope for a better planet; we all have a role to play in stepping up and speaking out to advocate for a healthy and safe environment. One tactic for climate advocacy is to use the power of athletes as communicators to liaise with spectators and participants. Sport organizations can align with non-profit organizations such as Protect Our Winter Canada, EcoAthletes, Players for the Planet, and Champions for the Earth to access training and resources to educate athletes, and leverage athletes’ platforms for climate advocacy.

Conclusion

In sport, we are accustomed to chasing continued improvement—and we can apply the same mentality to sustainability. The key here is not to get overwhelmed by everything you could do, and instead focus on what you can activate right now, one project at a time. Combined, these efforts will ensure safe and fun sporting opportunities well into the future.