Highlights

- The Government of Canada is committed to achieving gender equity in sport at all levels by 2035.

- Ongoing research has demonstrated the majority (over 90%) of Canada’s sport’s media coverage is focused solely on men’s sport, and that women and girls have lower sport participation rates than men.

- This article provides an overview of women and girl’s involvement in the Canadian sport sector and uncovers opportunities for future research and equity-driven work.

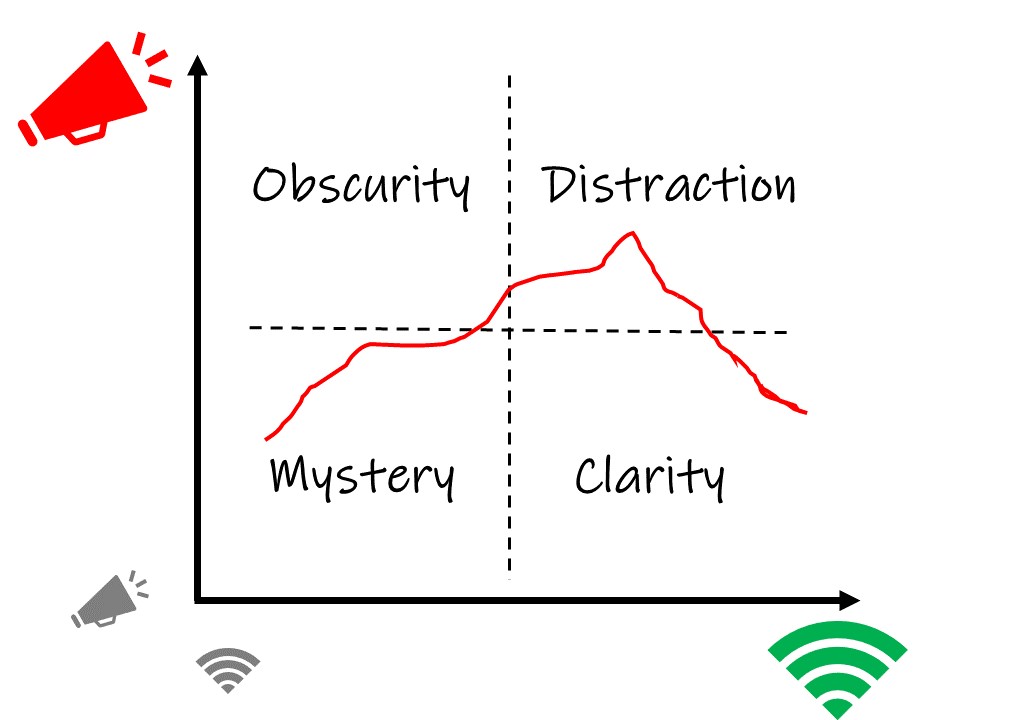

Signals = the truth

Noise = what distracts us from the truth

(Silver, 2015)

The Government of Canada is committed to achieving gender equality in sport at every level by 2035. But where are we in achieving this goal? And how do we know where we are?

The answers to these questions lie in the ability to gain reliable and accurate data. These data points are known as “signals” and they show where we’re on the path to achieving the goal. However, these signals are often muffled by “noise,” or other information offering little value or distracting from the original goal.

Within the sport system, researchers intentionally look for signals about women and girls to assess their advancement in this traditionally male-dominated sector. However, this isn’t easy work, because signals must be uncovered amid the noise. Signals and noise are 2 variables that are both independent and co-exist within systems (Wolfe, 2020).

To understand the presence or absence of gender equity within the Canadian sport system, there must be a quest for reliable data signals in areas that affect the system. Where do we look for reliable data? And how do we minimize noise in the system? In this article, we’ll take a look at the data we have in some areas, where noise still exists, and how we can chart a path to achieving clarity in the system.

Signals, noise and the search for clarity

This useful metaphor of signals versus noise was first introduced by Nate Silver, an American statistician. It’s the theme of his 2015 book The Signal and the Noise: Why so many predications fail – but some don’t (Silver, 2015). Silver argues that both science and self-knowledge are required to distinguish signals (truthful information) from noise (distracting information). Distinguishing them will provide clarity in a data rich system (Silver, 2015; Wolfe, 2020).

To illustrate this metaphor, here the y-axis shows low to high noise and the x-axis shows low to high signals. Within the graph, the 2 opposing axes create 4 quadrants of possible information scenarios.

In the “mystery” quadrant, the system is characterized by both low noise and low signal. That’s where the Canadian Sport system was when the goal of gender equity by 2035 was first announced. When a system is facing data “obscurity,” high levels of noise and low signals are experienced. And, in a space of “distraction,” there are high noise and high signals. Distractive scenarios are tricky, because lots of noise may create confusion, steering individuals away from the important and valuable signals they’re aiming for.

Optimally, the Canadian Sport system aims to operate in the quadrant of “clarity,” where signals are high and noise is minimal. This ideal outcome ensures the availability of true signals or noise-free data. This is the focus of the work of the E-Alliance, a knowledge sharing hub made up of scholars and partner organizations from across Canada. They’re dedicated to gender+ equity in sport and to providing clarity to the Canadian Sport system on gender equity.

Women and girls in Canada

High signals for demographic information come from Statistics Canada and present the diversity of Canada’s population. According to census data, over half of Canada’s population (50.9%) identify as women (Statistics Canada, 2016). This nearly even gender distribution is evident across children’s age categories: 49% of children under the age of 14 are girls, and 49% of teens (aged 15 to 19) are also girls (Statistics Canada, 2021). One in 4 Canadians identify as BIPOC (Black peoples, Indigenous peoples and Peoples of Colour) and 1.7 million identify as Indigenous (Statistics Canada, 2016). Further, depending on different data sources, between 3% and 13% of Canadians identify as LGBTQ+ (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender or Queer) (Jasmin Roy Foundation, 2017). Based on these signals, the Canadian population includes diverse individuals with intersectional identities.

But, what do we know about how many women and girls are participating in sport? And what do we know about the participation of women and girls with intersectional identities? Below, we dive into the signals for women and girls’ participation and leadership in sport, the role of sport media in providing signals or noise, and the path forward for gender equity in Canadian sport.

Women and girls in sport

Researchers have been working to provide good data or signals on women and girl’s involvement in sport. This cumulative work has led to strong signals on participation rates, changes and the reasons why women and girls may be missing from sport. We now know that girl’s sport participation rate drops by 22% as they enter adolescence, leading to a dropout rate of 1 in 3 girls leaving sport by their teens (Canadian Women & Sport, 2020). These changes are more staggering for girls with intersectional identities, as Indigenous girls have the lowest participation rate at only 24% (Canadian Women & Sport, 2020).

Ongoing work has provided insights on the complex reasons why girls choose to leave sport. These include socialization and gender expectations, lack of consideration for social identities, structural barriers and psychosocial barriers (Trussel et al., 2020). A strong signal for girl’s decreased participation came recently in work uncovering how COVID-19 affected girl’s sport: 1 in 4 girls aren’t committed to returning to their pre-pandemic sports (Canadian Women & Sport, 2021). Just imagine, if you looked at all Canadian girls in sport nationally, then this is the equivalent of every girl in Alberta deciding to stop participating in sport. A shocking value a time when sport may be more important than ever.

It’s thanks to the work of scholars dedicated to uncovering signals on girl’s participation that we now have these insights. We can use the insights to move forward with creating more inclusive sport environments and more sustainable sport experiences for girls. This ongoing research is critical to filling in signal gaps we have about girls who leave sport.

Importantly, this work prioritizes creating equitable sport experiences for all Canadian girls. That’s an important goal because we know that those with intersectional identities face more barriers to inclusion (Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport, 2022).

Women and girls in high performance sport

For professional women athletes, participation opportunities have grown over time. Consider the Olympics, the world’s largest sporting event, which began with no opportunities for women to participate. Over time, women’s participation in the Olympic Games has ebbed and flowed, but it has mostly grown to achieving near gender parity at the Tokyo 2020 Summer Games.

For the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games, Canada sent teams that were predominately women. Over half (60%) of the Canadian Olympic team, and 55% of the Paralympic team were women athletes (Canadian Olympic Committee, 2021a; Canadian Paralympic Committee, 2021a). Women athletes won the majority of Canada’s medals, winning 75% of Canada’s Olympic medals and 67% of the Paralympic medals (Canadian Olympic Committee, 2021b; Canadian Paralympic Committee, 2021b). Thanks to these signals, we can see there are high-stakes opportunities for women to participate within our sport system and that these athletes bring a high return.

For the 2022 Olympic Winter Games, Canada sent its most gender-equal team, with 106 women athletes and 109 men athletes. A strong signal of women’s increased participation in high performance sport.

Women and girls in sport leadership

Moving on, we take stock of how women are involved in sport leadership. A 2019 study, surveying over 20,000 people across 11 countries, found that Canadians were the most comfortable with women as leaders (Vultaggio, 2019). Canada’s results were higher than any other nation surveyed, as 53% of men and 65% of women reported they were comfortable with women in leadership positions (Vultaggio, 2019).

So how does this translate to the Canadian Sport system? Returning to the 2020 Olympic and Paralympic Games, we find that 47% of Paralympic coaches and 17% of Olympic coaches were women (Canadian Paralympic Committee, 2021c; E-Alliance, 2021). These findings are similar to the representation seen in university and college sports, where the majority of coaches are men (Canadian Women & Sport, 2020). The only exception was in the assistant coaching positions for women’s sport teams, where the number of women coaches is slightly higher than men (Canadian Women & Sport, 2020). Recent work has also shown that the overwhelming majority of the coaches in our university system are White (Joseph et al., 2021).

This overwhelming percentage of male coaches isn’t a sign of capability. Research tracing the performance of basketball coaches suggests there’s no gender gap for winning games. In other words, while men aren’t more capable, they still hold the majority of coaching roles (Darvin, Pegoraro & Berri, 2018).

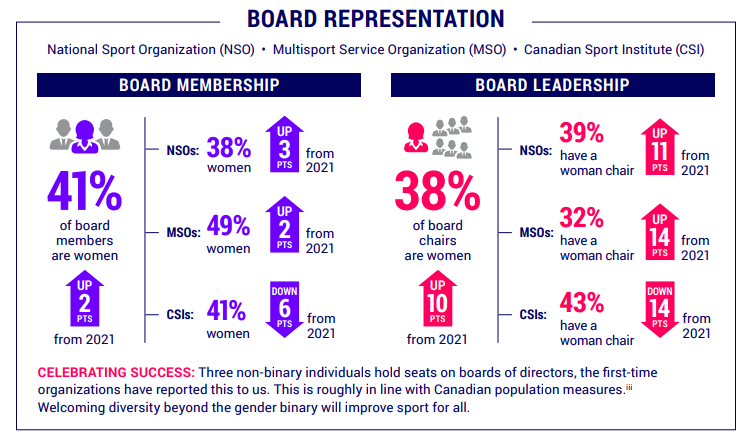

Outside of coaching, we can also review board member composition to look for signals around who is leading and providing oversight to Canadian sport organizations. In reviewing sport board membership and leadership, the number of board members who are women is increasing, with current estimates at 41% representation (Canadian Women & Sport, 2022). That value is encouraging. After all, it takes 30% of board membership to be individuals from diverse groups before changes toward equality are experienced (Tepper, Brown & Hunt, 1993). Importantly, gender-equal boards are associated with higher revenues and more financial resources (Wicker & Kerwin, 2020).

The role of sport media in providing signals or noise

Using these signals as a baseline, we turn our inquiry to how media represents women in sport, questioning if the Canadian sport media reflects women and girls’ participation in sport. Undoubtedly, Canadian sport media doesn’t accurately represent women athletes, and is a system full of noise. Arguably, the Canadian sport media may be labeled as a system of distraction, depicted by its high levels of noise and signals.

We’re currently conducting longitudinal research tracking print and online sport media coverage in Canada. While the data has yet to be published, preliminary findings show 92.6% of content is solely related to men’s sport coverage. However, concurrent research demonstrates that Canadians want to watch women’s sport content. But, they can’t find a place to watch it, despite 61% of girls (aged 13 to 18), 54% of women and 45% of men, wanting more women’s sport content available on television and online platforms (Canadian Women & Sport, 2020).

And when women’s sport is broadcast in Canada, viewership records are consistently broken. That demonstrates consumer demand. During the most recent US Open women’s single championship game, 1.1 million Canadians tuned in to TSN to watch the match between Emma Raducanu and Leylah Fernandez (Dunk, 2021). This is a higher viewer turnout than for the CFL game and Toronto Blue Jay’s game which aired at the same time (Dunk, 2021). On ESPN in the United States, the game attracted 3.7 million viewers, a value higher than the 2.7 million who tuned in for the men’s match (Reuters, 2021). Further, in the United Kingdom (Emma Raducanu’s home country), there were 9.2 million streams of the match on Amazon’s Prime Video, demonstrating that viewership of women’s sport takes place across viewing platforms (Reuters, 2021).

And what happened to these athlete’s personal following on social media platforms as a result of the final? Both amassed huge follower numbers on their social media profiles, with Raducanu gaining 363,300 and 1.2 million new followers on Twitter and Instagram, respectivelu. Leylah Fernandez had equally impressive gains of 72,000 on Twitter and 250,000 on Instagram, despite finishing second to Raducanu (Shitole, 2021; Akabas, 2021). These strong signals suggest the Canadian public is both interested in watching women athletes and in continuing to follow and engage with them after games.

In Canada, perhaps the most recent example of monumental support for women athletes was from the women’s gold medal soccer match during the 2020 Olympics. That game drew 4.4 million viewers, an audience of nearly 12% of Canadians (CBC Sports, 2021). To put it in perspective, far more Canadians watched the women’s soccer team win gold than watched the 2021 Stanley Cup final, which only captured an audience of 3.6 million (Tirabassi, 2021). This evidence provides a strong signal for women’s sport and Canadians’ desire to watch women athletes compete.

Why is this disconnect between sport media coverage and consumer interest in women athletes so important? While the media doesn’t tell us “what to think,” it does tell us “what to think about.” And today, our sports broadcasters are telling us to think a lot about men’s sport.

Despite this current climate, there’s a potential disruptor in the system. In 2020, on the eve of International Women’s Day, CBC Sports announced that it was committing to gender-based sport coverage across all its platforms (Butler, 2020). At the time Chris Wilson, CBC’s Executive Director of Sports and Olympics stated that the CBC was committed “to providing audiences with equal opportunity to watch, read about, meet and hear from female sporting heroes.” At the time, Olympian Jennifer Heil commented that this change may be integral in keeping more women and girls in sport (Butler, 2020). Now, we need to track this commitment and hopefully add more signal than noise to the Canadian sport media landscape.

The path forward

In this article, we summarize the current state of signals and noise in the Canadian sport system around the federal goal of gender equity by 2035. What do we know? That we still have a long way to go. While we may be close in some areas (such as board composition), when we dig further into the numbers for a true signal, we see there are just as many boards achieving high grades as there are achieving low grades for gender equity.

The same is true for senior staff in these organizations. While many organizations perform well in terms of gender equity, an almost equal number perform poorly with women in under 24% of senior positions.

The continued prevalence of weak signals and loud noise in the system is the reason that Sport Canada established E-Alliance. Its mission is to “provide credible thought leadership and generate an evidence base to support gender equity in sport through innovative, transparent and sustainable research activities, data curation, network building and partnerships, to effect pan-Canadian behaviour change.” E-Alliance’s initial research agenda has been formed around 4 pillars:

- Longitudinal data on participation and leadership

- Evaluation of programs and interventions

- The nature of the experience of women and girls in sport

- Transforming the system to meet the goal of gender equity

To advance gender equity in sport, it’s critical that more longitudinal studies and work investigate the lived experiences of all women and girls with sport. Specifically, research focusing on women and girls with intersectional identities must be prioritized so that all Canadians can experience the benefit of sport. We must continue to track how the global pandemic affects sport participation and ensure that sport rebuilds in a gender equitable way. That will safeguard that any gains before the pandemic aren’t lost, nor are women and girls set back further.

About E-Alliance

E-Alliance is a knowledge sharing hub dedicated to gender+ equity in sport. It’s made up of scholars and partner organizations from across Canada. E-Alliance is led by 3 co-directors: Gretchen Kerr, Ph.D. (University of Toronto), Guylaine Demers, Ph.D. (Université Laval) and Ann Pegoraro, Ph.D. (University of Guelph).

E-Alliance strives to:

- Act as the central resource hub for research on gender+ equity in sport and movement cultures in Canada.

- Build a sustainable pan-Canadian network of researchers on gender+ equity in sport, including graduate students and emerging scholars.

- Work with key partners in the sport community to translate research to practice.

- Fund innovative research that provides new ways of looking at persistent problems.

- Share research findings and data in accessible ways.

- Deliver consistent, trusted information about gender+ equity in sport and movement cultures to audiences nationally and internationally.