Many sport organizations collect data on their programs and best practices, but what happens with those findings? Unfortunately, this data often gets piled into internal reports and largely forgotten. This means that valuable learnings aren’t shared with those who can use them to inform future practices and advance the sport system.

As many organizations are ramping up for the upcoming sports season and are beginning to think about program evaluations, now is a good time to consider how organizations can use knowledge mobilization (KMb) principles to optimize evaluation findings.

In this blog, SIRC will review what knowledge mobilization is and why it’s crucial for the sports sector. SIRC will also provide tips and resources to help organizations plan knowledge mobilization activities.

Understanding knowledge mobilization

Knowledge mobilization is the process of sharing evidence-based findings with an audience who can use those findings in practice.

Depending on the knowledge you plan to share, your goals with your knowledge mobilization may vary. In the sports sector, common goals of knowledge mobilization are to:

Knowledge mobilization helps close the gap between what is known and what is done. Closing this “knowledge-to-action” gap can advance the sport sector by providing sport stakeholders with information that enables them to enhance practice, policies and programs. For example, knowledge mobilization can be used to synthesize the latest evidence on the topic of Safe Sport to inform the creation of policies and protocols that encourage safe, welcoming and inclusive environments for everyone involved in sport.

Mobilizing your knowledge

You may consider mobilizing knowledge whenever you complete a research project or evaluation with findings that could impact the current state of policies, programs or practice in the sport sector. This could include research and evaluation projects that you complete internally in your organization or in partnership with an academic researcher or institution.

For example, suppose you were evaluating the barriers newcomers to Canada face to participating in your community’s youth hockey program. After completing your evaluation, you could share your findings internally to identify strategies that may help improve accessibility and participation. You could also share these findings externally to begin discussions with other organizations who are facing or have faced similar challenges. Sharing your findings and best practices often leads to positive discussions and collaborations, which help move sport forwards.

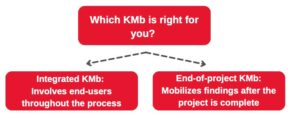

While knowledge mobilization activities often happen at the end of a project or evaluation like in the example above, this is not always the case. You may choose to engage in integrated knowledge mobilization, which is when you work with a group of knowledge users throughout your evaluation or project.

With integrated knowledge mobilization, you rely on the unique expertise and experiences of your end-users to inform every step of the research project, from identifying your research question to sharing your research findings. Taking a more integrated approach to your knowledge mobilization helps ensure that you are answering questions that your end-users have and that the way you disseminate the findings will be relevant and meaningful to them.

Identifying how and with whom to share your knowledge

Knowledge mobilization deliverables can take many forms, including but not limited to infographics, videos, reports, workshops and social media posts. When selecting how you will mobilize your knowledge, it is important to consider with whom you hope to share the knowledge, as different groups have different learning styles and preferences. For example, if you are targeting athletes with your dissemination, you may rely primarily on social media. However, when targeting coaches, you may rely more on videos or infographics that could be shared within a newsletter or learning module. In many cases, sharing your knowledge using various dissemination tools is beneficial as it helps ensure you reach all your targetted end-users.

Tips to help you get started

- Think about what knowledge you want to share. Consider why sharing this knowledge is important. How will it contribute to the sport sector?

Identify your end-users. Think about what end-user(s) you want to reach with this knowledge. Why is it important that they learn about this information?

Identify your end-users. Think about what end-user(s) you want to reach with this knowledge. Why is it important that they learn about this information? - Create a list of key messages. Identify the key points that you want to share. Make sure these points are clear, concise and written at a level your targeted end-users will understand.

- Consider how you want to share your knowledge. Look into different dissemination tools and identify which will be most appropriate for your end-users. When deciding on the dissemination tool(s) you will use, you should also consider the timeline for your project and the cost of the different dissemination tools.

Recommended resources

- Ontario Centre of Excellence for Child & Youth Mental Health – Knowledge Mobilization Toolkit: http://www.kmbtoolkit.ca

- Government of Canada – Knowledge Translation Planner: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/reports-publications/grants-contributions/knowledge-transfer-planner.html

- The Hospital for Sick Children – Knowledge Translation Planning Template: https://www.sickkids.ca/contentassets/4ba06697e24946439d1d6187ddcb7def/79482-ktplanningtemplate.pdf

- The Hospital for Sick Children – The Plain Language Writing Checklist: https://www.sickkids.ca/contentassets/92c5abda231e44b6832f5e3effeacdf8/plain-language-checklist_jan2017-sickkids-kt-program.pdf

Identify your end-users. Think about what end-user(s) you want to reach with this knowledge. Why is it important that they learn about this information?

Identify your end-users. Think about what end-user(s) you want to reach with this knowledge. Why is it important that they learn about this information?