“City of Ottawa, recreational outdoor programs & leagues are cancelled today, June 7 due to poor air quality in the Ottawa region.”

Canada is in the midst of a record-breaking year for wildfires, which directly impacts air quality. Accordingly, multiple cities closely monitored the air quality and announced the cancellation of outdoor recreation activities. The Sport Information Resource Centre partnered with Health Canada in 2022 to develop and distribute resources about air quality and safe outdoor sport participation, which was released in February 2023.

Perhaps many of you have begun to wonder about these things: What kind of future will we face if these air conditions continue? How would we adapt or modify our outdoor activities to poor air quality? How should we respond to solve the problem?

Given that environmental degradation is accelerating in Canada, lessons learned from South Korea can be applied to the Canadian context and offer us some answers to these questions. In this post, as a PhD Candidate researching air quality and sport in the South Korean context, I present a South Korean example of how people use mobile apps to navigate outdoor activities in poor air quality. I also discuss how this illustrates the need to examine and tackle larger structural issues to address the problem.

South Korea’s air quality and particulate matter

Over the past decade, poor air quality has emerged as one of the biggest social, environmental and health issues in South Korea (N. H. Kim et al., 2019). Although the main contributors to poor air quality are different such as wildfires in Canada and industrial air pollution in South Korea, the primary pollutant is the same, which is particulate matter (PM).

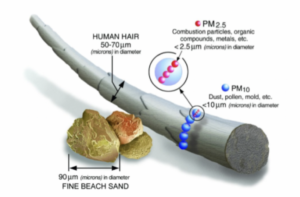

PM is a general term referring to a mixture of solid and liquid particles suspended in the air. PM is known for its harmful composition, and due to its small size, it does not get filtered by the nostrils. The particles penetrate lung and nostril tissues, causing inflammation in organs as they travel deeper into the body. Exposure to high concentrations of PM is associated with increased mortality and morbidity, both in the short and long term (WHO, 2021). PM can cause respiratory and cardiovascular diseases as well as mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety (Braithwaite et al., 2019; S. J. Kim et al., 2020; The WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2013).

Outdoor sport and response manual

To respond to the growing public concern about the adverse health effects of air pollution, the South Korean government has set indexes to assess the PM level and clearly communicate health messages. In 2019, the Korea Sports Safety Foundation, a sport organization affiliated with the Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism, released the Particulate Matter and Heat Wave Response Manual for Sports Administrators.

The manual advises sport administrators to evaluate the safety of outdoor activities using the vulnerability rating system in addition to the air quality forecasts and alerts. The vulnerability rating system consists of the duration of exposure to PM and a list of each sport’s metabolic equivalent of task (MET) values. MET is a standardized unit that indicates exercise intensities by measuring the amount of oxygen consumption during physical activity. The greater the MET value, the more oxygen and PM one breathes in, increasing associated health risks.

Following government policies and health recommendations, many South Koreans suspend outdoor activities or modify the type or location of activities. As a result, many people think that “having to limit their outdoor activities” is the most distressing impact of PM on their daily lives even more than “their health deterioration” (Korea Environment Institute, 2018).

Mobile phone applications and lived experiences of poor air quality

Today, South Koreans have made it a habit of checking their mobile phone PM application (app) to guide outdoor activities (Korea Environment Institute, 2018; Park et al., 2019). The PM app is created as a risk communication tool with the idea that if people are informed, they will act in a way that reduces their exposure to risks (Y. Kim et al., 2017; Yi et al., 2019). However, this technology often complicates people’s perceptions of the air.

Today, South Koreans have made it a habit of checking their mobile phone PM application (app) to guide outdoor activities (Korea Environment Institute, 2018; Park et al., 2019). The PM app is created as a risk communication tool with the idea that if people are informed, they will act in a way that reduces their exposure to risks (Y. Kim et al., 2017; Yi et al., 2019). However, this technology often complicates people’s perceptions of the air.

For example, people have started developing and applying personal legends. People comprehend the PM level directly by observing reduced visibility and blurry skylines. People also use their senses of pain, such as scratchy throats and dry eyes. Then people notice that the air quality displayed on the app occasionally differs from how their bodies actually read and feel the air.

One user left a review on Google Play saying, “I can kind of know PM just by looking at the mountain at the back of my house… The PM level I see with my own eyes is Extremely Bad [level], but [the app] says only Bad [level]….”

This incident can also be applied to sport settings, where sport organizations tell their athletes that it is safe to play outside based on the Air Quality Health Index (AQHI), but the athletes might think otherwise based on what they see, smell, and feel. These instances show that the AQHI may not always be reliable and not be the absolute solution.

The disconnect between what users see on the app and what they see with their own eyes may occur due to the wind, varying light levels, and the air monitoring system (Jang, 2019; C. S. Kang, 2019; J. A. Lee, 2017). However, this discrepancy makes people feel anxious and unsafe, prompting them to wonder why this difference is occurring and who is responsible for this issue.

Interrogating the system and government

PM apps shed light on the stories that bodies tell. These stories make people not just passively receive and follow the health messages given to them. They further provoke irritation and worry, making people critically view broader structures that shape air quality.

Another user commented with frustration, “It would be better to check the air quality with our own eyes. I wonder if this is a problem with the air monitoring station or the app itself.”

People start to doubt the current air monitoring and management systems, eventually leading to collective actions like protests and petitions (M. K. Kang, 2017; Seo, 2019; Shin, 2016). People critique the government for its negligence in imposing heavier regulations on polluting industries and implementing stricter air quality standards. They further pressure the government to install additional air monitoring stations near where people live, walk, and move, not just on top of buildings (M. K. Kang, 2017; Y. M. Lee, 2017).

Final thoughts

Delivering air quality information and health messages is not an easy and quick fix to ensuring safe outdoor activities, as the South Korean example demonstrates. Instead, it can often be challenged by what our bodies tell us. It is also a short-term remedy that temporarily adjusts individuals’ behaviours (Marzecova & Husberg, 2022).

Canadians should acknowledge that protecting people from poor air quality requires more extensive and fundamental interventions. Outdoor sport is one of the sectors that is adversely impacted the most by poor air quality, and thus, has the potential to raise people’s awareness of the issue.

Therefore, sport can serve as a strong impetus for collective movements to hold the government accountable for cleaner air. For Canadians to continue to enjoy the sport they love, athletes, coaches, and parents can urge their sport organizations to act collectively to develop more long-term and sustainable strategies.