Sport is the most watched, celebrated, supported, and engaging social endeavour in the world (Hulteen et coll., 2017). Sport is inherently emotionally and narratively captivating, embodying and upholding principles of positive and sustainable human, social, and environmental development. But the potential for sport to do good for participants and society more broadly relies on sport cultures and environments that centre participants and uphold positive social values.

Cultural change is not as difficult as we may believe, and we all have the power to shift and strengthen the culture of our sport environments. Cultural change begins with understanding the mechanics of culture in organizations and the relationship between organizational climate, structures or artifacts, trust and engagement. Next, one must access the tools to “audit” the organization for cultural fractures. Most importantly, identifying accessible mechanisms to personally affect cultural change within your program or organization equips you to do the work.

In this blog, I outline the mechanics of cultural change and provide tools and resources for sport leaders and administrators looking to change the culture of their sport.

The blueprint and materials

Part of the enduring challenge facing sport leaders who are struggling to address violence, cheating, abuse and discrimination in sport is that the cultural norms that bind sport structures have not changed. To change culture, we need to first audit the culture by peeling back or drilling down through the layers of values and beliefs in order to expose, and then challenge and change, some of the governing assumptions within sport. Typically, leaders re-examine goals, values and priorities without examining the fundamental beliefs and assumptions driving them.

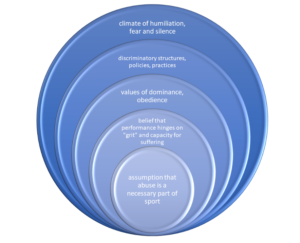

Schein’s (2010) theory of organizational culture provides a useful lens through which to view sociocultural forces within sport. Schein compares culture to an iceberg or onion (Figure 1).

On the surface one will find:

- Climate (feelings, atmosphere)

- Artifacts (structures, policies, texts, behaviours)

Operating below the surface, however, linger:

- Values, beliefs, and assumptions shaping and influencing the concrete representations on the surface

For instance, currently, we see abuse in sport. Artifacts of abuse on the surface level include discriminatory behaviours, rules, team policies, and actions. For example, Figure 1 illustrates how a person in authority may demean an athlete, discriminate against them based on their appearance or behaviour, humiliate them in front of their peers, exclude them from team activities, punish them for mental or physical injury or illness by prohibiting them from further training and development.

This abuse is justified as valuing “grit,” coupled with a belief that a specific body type, or pushing through injury and illness are a sign of that grit. An individual’s capacity to endure abuse is seen to be the path to grit and high performance. These beliefs represent the fundamental assumption that high performance can only be achieved via 1 path, and that abuse is not only okay, but necessary, to reveal true strength within an athlete. Within this example we also see a narrow-minded assumption that athletes are born, not developed.

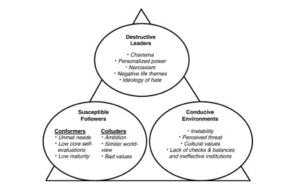

Roberts, Sojo and Grant (2020) and Thoroughgood and Padilla (2013) describe the organizational artifacts, values and assumptions that lead to abuse as a toxic triangle (Figure 2). A destructive leader’s abuse of power can lead to a climate of fear, instability, and lack of accountability as well as the valuing of dominance, abuse, control and compliance. To endure such an environment, followers tend to rely on conformity (complying with the norm) or collusion (exploiting norms further for one’s own benefit).

The tools and skills

Cultural change in sport must begin with revealing and challenging the assumptions of exceptionalism that have become common in sport leadership but are at odds with the true potential of sport for society. Replacing existing hierarchical assumptions with the foundational principles of duty (of care) and responsibility (to lead and model social values) would reconstruct the foundation of sport and manifest the values of respect, friendship, and excellence through artifacts of equitable structures and policies, developmental practices, and caring behaviours.

Through his work with Own the Podium, alongside partners the Canadian Olympic Committee and Canadian Paralympic Committee, University of Ottawa professor and mental performance consultant Dr. Kyle Paquette offers a promising model that places people and performance at the foundation of sport (the “culture of excellence” model). These values in turn shape the cultural artifacts (attitudes, structures, behaviours, and practices) of an excellent sport experience for all participants.

Tips for getting down to the cultural work:

- Identify space and time to conduct a thorough audit using tools like the Barrett Values Assessment, or a facilitated workshop

- Revisit organizational core values to ensure the values are shared

- Engage relevant audiences to participate in the audit

- Remind the groups that identifying cultural incongruities and fractures are essential: “cracks are where the light comes in”

- Ensure that all artifacts, practices, and behaviours across the environment reflect the shared values

- Establish a regular review and re-alignment process

Cultural audit “check in” exercise:

Engage in a cultural audit “check in” exercise by answering 3 questions with your colleagues or teammates:

- What do we value?

- In what ways do we contradict our values?

- How can we bring our behaviours into alignment with our values?

Reframing sport: From dominance and privilege to partnership and excellent sport experiences for all

Sport at its centre is for the purpose of developing human beings (mentally, physically, emotionally, socially) for the sake of developing society as a whole. Sport delivery is therefore a partnership between participants (athletes, volunteers, and fans) and sport leaders (coaches, officials, administrators and practitioners) working for a shared goal of excellent experiences for all (Walinga, Obee, Cuningham & Cyr, 2021). By placing “excellent experiences for all” at the centre of our shared purpose in sport, gold standards (not gold medals) will return sport to the shared values of respect, friendship and excellence.

Excellent experiences in sport can look very different for each participant in sport: fun for the recreational, friendship for the young, having one’s best race for the high-performance athlete, helping an athlete achieve a personal best for a coach, a clean and safe game for a referee, or an exciting tie breaker for a spectator. With excellence for all at the center comes partnership and with partnership, a more global perspective of sport. With human and social development as the central governing principle of our sport culture, we are inspired to be caring of ourselves and one another, open to innovation, inclusive of newcomers with potential, aligned in our focus, trusting in our process, and committed to our relationships, our community and sport as a whole.