Community sport organizations (CSOs) occupy an important place in our communities by providing sport and recreation opportunities for all ages, as well as serving a wider social role within our communities (see, for example, Taking Action: Community Sport Organizations and Social Responsibility by Misener, 2018). Previous research has pointed to the challenges these organizations face, including growing demands for services, competition for resources, and greater accountability to stakeholders and funding partners (Musso et al., 2016; Nichols et al., 2015). These challenges are not unique to CSOs but are perhaps accentuated in Canadian sport context given the reliance on a volunteer workforce, modest budgets, and the relatively informal nature of their organizational structures (Doherty et al., 2014). Perhaps now, more than ever, with unique challenges and uncertainty introduced as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, a strategic approach to capacity building may be particularly useful (see recent “Return to Community Sport” commentary). This article introduces a model of capacity building, providing an approach for CSOs to address challenges and leverage strengths in order to achieve program and service delivery goals.

What’s involved in a strategic approach to capacity building?

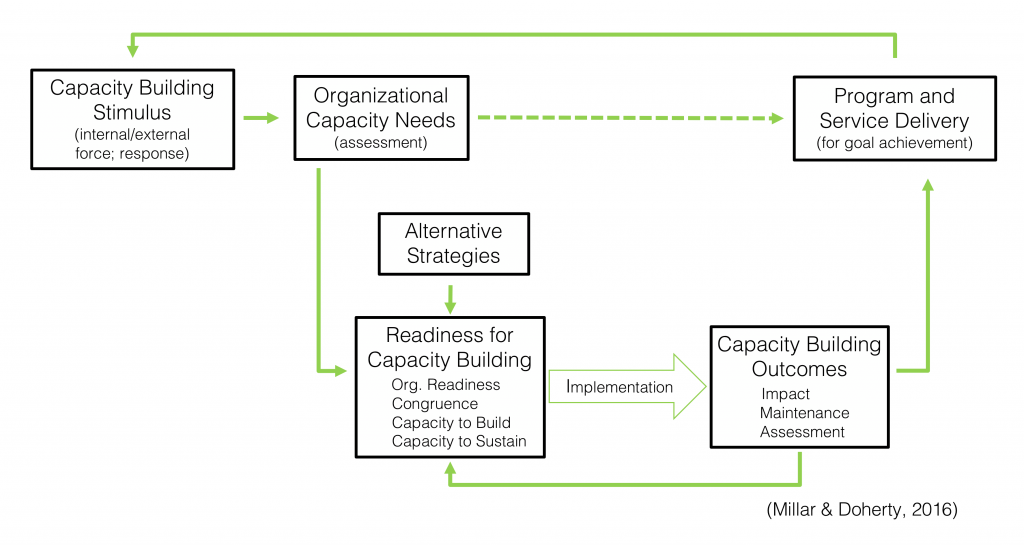

Capacity building refers to developing an organization’s resources (e.g., human, financial, infrastructure, planning, external relationships) and improving its ability to use those resources to successfully respond to new or changing situations (Aref, 2011). Based on learnings from two case studies and 144 cases of capacity building in CSOs, and existing research in this area, we developed, and subsequently examined, a process model that provides a step-by-step roadmap for organizations engaging in capacity building (see figure below; Millar & Doherty, 2016). Within the Canadian sport context, we believe the use of a targeted approach to capacity building that addresses the unique strengths and challenges of individual organizations will be most effective.

Step 1 – Identify the reason for engaging in capacity building

Our findings revealed that successful capacity building begins when a stimulus is placed on an organization. Therefore, in order to begin the capacity building process with a clear vision and a strategic focus, CSOs should pay particular attention to the forces within their internal and external environments. These forces trigger the organization to determine an appropriate response – one that will address the nature of the specific force and that is reasonable for the organization to pursue. Together, the force and associated response represent the stimulus for capacity building. Capacity building in the CSOs involved in our research was most often triggered by decreasing club membership, new programming demands, or conflict with club partners. In response to these forces, CSOs chose a range of strategic responses, such as introducing new programs or initiatives to attract members, targeting recruitment efforts, altering registration fees, and introducing recruitment and training initiatives for volunteers, coaches, and board members. Clearly understanding the stimulus that drives capacity building will ensure CSOs invest their time and energy effectively.

Tip: Organizations do not (and should not) engage in capacity building efforts simply for the sake of doing so – there should be some external or internal force that requires a response from the organization.

Step 2 – Conduct a thorough capacity assessment and identify capacity building objectives

Whether or not an organization responds to an environmental force depends on its capacity to do so. The particular capacity needs associated with a given stimulus will vary depending on the current state of the organization. For instance, a CSO experiencing decreasing membership may choose to respond by introducing a membership development program. The organization would then assess its current capacity to move forward with this initiative, identifying any capacity needs or assets that may hinder or facilitate that action. Capacity needs or assets may be related to the organization’s human resources (e.g., number of volunteers, certified coaches, level of expertise among executive members), financial resources (e.g., available funds, stability of revenue sources), existing relationships (e.g., quality of partnerships), planning (e.g., alignment with strategic plan), or existing infrastructure (e.g., access to facility space, equipment) (Doherty et al., 2014; Hall et al., 2003). If no capacity gaps exist, then the club moves forward with the proposed response (in this case, the membership development program). However, if gaps are present, the extent and nature of those capacity needs become the basis for the organization’s capacity building objectives. This is a critical step in ensuring that the capacity building process will address the specific needs of the organization – if the objectives are not clear and specific, capacity building efforts are likely to lack focus and, ultimately, be unsuccessful.

Step 3 – Select strategies that align with capacity building objectives

It is important for organizations to choose capacity building strategies that align with their specific capacity needs. An organization may identify a number of potential strategies to address its capacity building objectives, whether those strategies are internal (e.g., re-allocating existing funds, recruiting coaches from existing membership) or external (e.g., applying for government funding, recruiting new volunteers, enrolling in workforce training) to the organization.  Our findings revealed that a key difference between the successful and unsuccessful cases of capacity building were the specific strategies chosen by each organization. Successful capacity building efforts often considered new and untried alternatives that were supported by members, aligned with the organization’s priorities, and were inline with what the CSOs had the capacity to pursue. In contrast, unsuccessful efforts often relied on those strategies that were “easiest and cheapest to do” and, as a result, failed to effectively address the identified capacity gaps. Capacity building strategies are only as strong as the planning that precedes their implementation (Cornforth & Mordaunt, 2011).

Our findings revealed that a key difference between the successful and unsuccessful cases of capacity building were the specific strategies chosen by each organization. Successful capacity building efforts often considered new and untried alternatives that were supported by members, aligned with the organization’s priorities, and were inline with what the CSOs had the capacity to pursue. In contrast, unsuccessful efforts often relied on those strategies that were “easiest and cheapest to do” and, as a result, failed to effectively address the identified capacity gaps. Capacity building strategies are only as strong as the planning that precedes their implementation (Cornforth & Mordaunt, 2011).

Step 4 – Consider whether your organization is ready to engage in capacity building

Effective capacity building relies on overall readiness to engage in those efforts. Our research showed that readiness is based on three factors;

- Organizational readiness – the degree to which board members and volunteers are willing, able, and motivated to support capacity building;

- Congruence – the alignment of capacity building objectives and strategies with existing organizational processes, systems, and day-to-day operations; and

- Existing capacity – the availability of existing capacity that can be leveraged to support and sustain capacity building efforts.

We found that the willingness and commitment of individuals within the successful case study was a key factor leading to that success; while animosity, lack of commitment from organizational members, and general disinterest in the capacity building efforts were key factors in the capacity building “failure” witnessed in the unsuccessful case study. Our findings also showed that congruence in the context of capacity building can be understood in two ways – at the micro-level, where day-to-day operations align with the workload involved with capacity building; and at the macro-level, where the club’s objectives, values, and mandates align with the capacity building efforts undertaken.

Our study of 144 cases of capacity building in CSOs across Ontario examined how ready they were for capacity building, and whether that level of readiness had an impact on the outcomes of those efforts (Millar & Doherty, 2020). Three key findings emerged:

CSOs were most ready for capacity building in terms of the alignment of those efforts with existing club objectives, mandates, and values. Clubs are engaging in capacity building efforts that are congruent with their unique organizational contexts.

CSOs were most ready for capacity building in terms of the alignment of those efforts with existing club objectives, mandates, and values. Clubs are engaging in capacity building efforts that are congruent with their unique organizational contexts.

CSOs were ready for capacity building in terms of having willing, committed, and motivated organizational members to drive the efforts forward. Clubs are relying on the willingness and commitment of their members (volunteers and board members) to drive capacity building efforts forward.

CSOs were ready for capacity building in terms of having willing, committed, and motivated organizational members to drive the efforts forward. Clubs are relying on the willingness and commitment of their members (volunteers and board members) to drive capacity building efforts forward.

CSOs were least ready for capacity building in terms of having existing resources and assets that could be used to facilitate those efforts. Existing capacity also had a unique impact on capacity building outcomes, meaning that the resources an organization possesses are particularly critical in ensuring successful capacity building.

CSOs were least ready for capacity building in terms of having existing resources and assets that could be used to facilitate those efforts. Existing capacity also had a unique impact on capacity building outcomes, meaning that the resources an organization possesses are particularly critical in ensuring successful capacity building.

Capacity building efforts should only be undertaken when they align with the organization’s mission and existing operations, and when the organization can rely on existing resources to support those efforts. Any incongruence or overstretching of organizational resources will likely result in unsuccessful attempts at building capacity or will leave the organization in a less desirable position in the end. Our results showed that the more ready an organization is to engage in capacity building (across all three factors), the more likely they are to achieve their desired capacity building outcomes. In other words, organizations with willing and motivated people, who embark on capacity building initiatives that fit with how the organization operates, and who have resources that they can lean on, are more likely to be successful in their efforts to build capacity and to successfully address the needs of their organization.

Step 5 – Evaluate the short and long-term outcomes of capacity building

Successful capacity building results in both immediate and long-term changes to an organization’s capacity that ultimately contribute to program and service delivery. Whether an organization experiences the desired short and long-term outcomes depends on whether the above steps are followed in a strategic manner. In addition to assessing the impact of capacity building efforts, the attainment of capacity building goals, and addressing the initial environmental force, evaluation of capacity building outcomes is also likely to uncover additional capacity needs and may trigger a reassessment of the organization’s readiness to engage in the capacity building efforts, as depicted by the feedback loop in Figure A (above).

Capacity building during times of change

This articles summarizes our research findings to provide a step-by-step process for CSOs as they engage in capacity building, which may be particularly timely as sport organizations across the country navigate the new sport realities that we are facing as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. As sport resumes across the country, and with the risk of future lockdowns, organizations will be facing new challenges and pressures from their environment that require capacity building in one way or another. The approach and insights outlined here provide a framework for organizations as they work to balance, address, and prioritize capacity building efforts, and to determine whether they are ready to engage in those efforts prior to doing so.

This research was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.