2018 is an exciting year with four major international sporting events on the calendar: the Olympic and Paralympic Games, the Commonwealth Games, and the Arctic Winter Games. These events are embraced by those with a love for sport, including the millions of spectators around the world, athletes, coaches, sport organizations, organizing committees, corporate partners, volunteers, and the media. However, the hosting of these major events is not without controversy, as is evidenced by multiple cities deciding not to bid (e.g. Boston and Toronto for the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games), withdrawing their bid (e.g., Budapest for the 2024 Olympic and Paralympic Games), or deciding not to host even when awarded (e.g., Durban for the 2022 Commonwealth Games).

As Canada considers bids for the 2026 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games, and the 2030 Commonwealth Games, this article examines the economic, tourism, social and sport participation impact claims of major international sport events. To maximize positive and minimize negative outcomes from hosting major sport events, we recommend a shift in thinking that builds on the opportunities smaller scale events present for host communities.

Economic Impact

Major sporting events require considerable financial, human and material resources. If these events would generate a profit, private enterprises would be the first in line to host these events. In reality, only a small portion of the money to host these events comes from private corporations in the form of TV rights and sponsorship. Most of the money to host these events comes from the local, provincial, and/or federal governments (i.e., tax-payers). This financial support from the government is an “opportunity cost”, meaning that this money could have been spent on other municipal, provincial/territorial or federal projects which may potentially generate more substantial and sustainable returns on investment.

Thus, a two-pronged question arises: (1) “Why is there a consistent tendency to overestimate the economic benefits and underestimate the costs for hosting major sport events (Kesenne, 2012)?” and (2) “What can be done to optimize economic impact?”

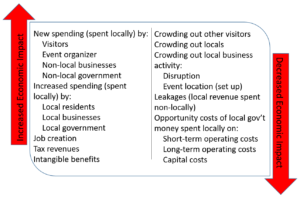

Contributing to the overestimation of economic benefits is the temporary “shock” in the economy a major sport event creates when the demand for a range of products, services and facilities rises dramatically for a relatively short period of time. However, not all of this economic activity contributes positively to the community or region where the event is hosted. A cost-benefit analysis reveals the true complexity (see Figure 1). On the benefit side there is new and increased spending, job creation, tax revenues and intangible benefits (e.g., the feel-good-factor). On the cost side, there are crowding out effects (e.g., regular tourists, residents, and local businesses), leakages (i.e., local money not staying locally – e.g. using local money to import materials to build facilities), and the opportunity costs (i.e., government spending as explained above).

Figure 1 – Economic Impact Drivers (Source: Agha & Taks, 2015, p. 203)

To attain optimal economic impact, the resources needed to stage the event (human, financial and physical) – the Event Resource Demand (ERD), must equal the resources available in the host city – the City Resource Supply (CRS) (Agha & Taks, 2015). Few cities have the necessary resources or capacity required to host major sport events, which prevents cities from achieving optimal economic impact. Thus, the key to attaining optimal economic impact is to find the best “fit” between the event and the host city. Does the city have required facilities? Does the city have the necessary hospitality capacity (hotel rooms, bars, restaurants)? Smaller sport events with fewer events and smaller delegations, and/or events hosted across several locations, are more likely to match the ERD and CRS. Increasing revenue from private sources to reduce the need for financial support from governments is another economic optimization strategy that should be considered.

Tourism Impact

Enhancing tourism is often considered a benefit of hosting major international events, in terms of both “flow-on tourism” (i.e., tourism activities beyond the event but around the time of the event), and post-event tourism.

In the case of major sport events, flow-on tourism can be problematic. An enormous influx of sport event tourists can contribute to large crowds and long waiting lines at classic tourism activities during events, reducing access for others. They may also crowd out regular tourists, thereby negatively impacting the number of tourists engaging in classic tourism activities (e.g. visiting museums, sight-seeing tours). This was the case at the London 2012 Summer Olympics and Paralympics, where the number of visitors to museums was down substantially (Woodman, 2012, July 31).

Smaller scale events are better positioned to capitalize on flow-on tourism because they are less likely to crowd out regular tourism, and the influx of tourists is more manageable. Moreover, when smaller scale events draw new visitors to the area, collaboration with destination marketers can showcase aspects of the city beyond the event and provide opportunities for sport event tourists to explore other attractions in the area. This creates added value to the tourism experience and increases the likelihood of benefits for the host city.

Post-event tourism is often one of the objectives of cities to host major sport events – putting their city “on the map” as an international tourist destination through branding and positioning. However, studies have not been able to measure substantial gains in post-event tourism that can be attributed to the hosting of major sport events (Solberg, Preuss, & others, 2007). Identifying gains or losses in post-event tourism is extremely difficult, given that tourism behaviour can be impacted by many unforeseen factors, such as terrorism attacks or epidemics (Toohey, Taylor, & Lee, 2003).

Smaller scale events may not have the same potential to put a city “on the map” as such, but organizing committees are able to showcase their expertise in hosting the sport(s) in question. By successfully hosting competitions, they will be recognized by the “sport community” worldwide (in the case of an international sport event). Thus, the city and the organizing committee create a name for themselves, putting them on the world map within the sport community, and increasing their ability to attract future events, and future sport event tourists, to the city.

Social impacts

There is evidence of sustainable and even tangible social outcomes of major sport events, such as Olympic parks (e.g., the 1988 Calgary Winter Olympics) where people gather and socialize many years after the event. However, social impacts of major events are more often referred to as intangible impacts, such as feelings of euphoria, enhanced national pride, and unity. Much of this evidence is anecdotal, and the “feel-good factor” that sport events generate is short-lived (Gibson et al., 2014).One of the problems from a social impact perspective is that International Sport Federations utilize a top-down-strategy when it comes to organizing their event(s) (Horne, 2015). This risks displacing local residents as decision-makers, and deprioritizing local development and legacy goals.

In contrast, smaller scale events have the potential to create tighter social networks and connectedness among residents through the utilization of bottom-up strategies that engage residents in planning and decision-making (Taks, 2013). This instills a stronger sense of ownership amongst residents, and a stronger foundation for delivering positive social outcomes. For example, smaller scale events provide more opportunities for personal growth and skill development amongst residents because: (1) there is a greater likelihood that residents take part in the planning and management of smaller scale events; and (2) they create more opportunities for local people to execute meaningful roles (e.g., through volunteering, officiating, and organizing). Further, smaller scale events have the potential to deliver on community goals. Consultation with local residents about their priorities (e.g., opportunities to strengthen community-based leadership, create new community activities) should be integrated from the outset, and specific tactics and strategies put in place to deliver.

Sport Participation Impact

Since “sport” is the core of sport events, stimulating sport participation is a plausible expected outcome. Claims that major international sport events will foster sport participation are found in bid documents, and are based on the notion of the so called “trickle-down”, “demonstration” or “inspiration” effects (Weed et al., 2015). This notion suggests that the successes of elite level athletes will inspire others to become more active and get involved, resulting in increased levels of sport participation and physical activity.

The Olympic Games, like no other event, attracts unparalleled interest from people around the world. So, the Olympic Games could be considered a powerful tool to create awareness for sport and sport participation. But while there is evidence that more people watch sport during the Olympic Games (Toohey, 2008), evidence supporting the “trickle-down effect” on participation is mixed. A systematic review carried out by Weed and colleagues (2015) revealed that: (a) those people who already do a little sport can be inspired to do a little more; (b) those people who have played sport before can be inspired to play again; and (c) some people might give up one sport to try another. This suggests capacity to enhance sport participation by retaining and developing existing participants, rather than recruiting new participants into sport. Craig, Bauman, and colleagues (2014) performed rigorous measurements of sport and physical activity among Canadian children aged 5–19 years (n = 19,862) between August 2007 and July 2011 (including the use of pedometers) and found no measurable impact on objectively measured physical activity or the prevalence of overall sports participation among children, in British Columbia nor nationally, despite new community programs created as a legacy of the Vancouver 2010 Olympic and Paralympic Games.

Sport facilities offer another avenue for sport participation and development incentives. Major sport events systematically require either the upgrading of existing sport facilities, or the construction of new ones. These high-end facilities too often become “white elephants” – costing a lot of money to build, but remaining unused or closing because they do not meet the needs of the local community or carry extravagant maintenance costs (e.g., multiple venues at the Athens 2004 and Rio 2016 Olympic and Paralympic Games, including Rio’s Maracanã Stadium). However, there are facility success stories. The Calgary Olympic Park became a National Training Centre with a primary goal to develop high performance sport, while also providing sport opportunities for residents. Another example is the Richmond Olympic Oval, which was initially built to serve as the 2010 Winter Olympic speed skating venue, and later downsized to meet the community needs. Note, however, that this came with a very high cost, and the facility could have been built at a much lower cost without hosting the Olympic and Paralympic Games. Considering how facilities can be built to become well-used legacies, rather than white elephants, is critical to optimizing the impacts of hosting.

Similar to major sport events, there is evidence that the hosting of smaller scale events stimulates sport development by providing opportunities for those already in sport to improve their performance through the access of better equipment, better facilities, increased competition experience, enhanced official and coaching capacity (Misener, Taks, Chalip, & Green, 2015). While no evidence exists for new participation in sport, host committees should encourage local sport organizations to use the event to attract new participants. Research has shown that local sport organizations (LSOs) lack the capacity to develop and implement sport participation strategies and tactics to attract new participants in their sport in conjunction with a major sport event (Taks, Green, Misener, & Chalip, 2017). Thus, helping LSOs to build that capacity, is an opportunity for host committees to boost the sport participation impact of the event.

Recommendations

In order to maximize positive and minimize negative outcomes from hosting major sport events, we recommend a shift in thinking that builds on the opportunities smaller scale events present for host communities.

- Find the best “fit” between the event and the host city (or cities) with regard to necessary and available resources, as well as the sport “appeal” for the local residents. Consider breaking large events into smaller entities by spreading the event across several locations who have the necessary resources and capacity.

- Secure as much revenue from private sources as possible to keep the need for government financial support to a minimum.

- Work with local Destination Marketing Organizations to create additional tourism opportunities and enhance the experience of visitors.

- Stage the best possible quality event, as this will put the host community on the map within the sport community; they will want to return.

- Apply a bottom-up strategy when planning and implementing an event to create more coherent, tighter and sustainable networks within host communities. Offer meaningful roles to residents in the planning and organization of the event, and integrate the needs and interests of the community with respect to facility and program development from the beginning.

- Help local sport organizations build their capacity to add an event into their marketing-mix to attract new participants in their sport.

Looking to the future and the possibility of Canada hosting the 2026 Winter Olympic and Paralympic Games and the 2030 Commonwealth Games, these recommendations can help ensure the organizing committees find ways to create more desirable outcomes and durable benefits for host communities, particularly from an economic, tourism, social and sport participation perspective.