Highlights

- The Mental Health Strategy for High Performance Sport in Canada aims to improve the mental health outcomes for all Canadian high performance athletes, coaches, and staff.

- The strategy was developed by Canadian experts in mental health and sport based on scientific evidence, applied experience, and international best practices.

- The newly formed strategy focuses on prevention, education, and giving everyone in sport the tools and skills to maintain positive mental health.

- This article provides an overview of how and why we developed the strategy, lists ways that sport leaders can begin to implement aspects of the strategy, and answers frequently asked that national sport organization leaders and staff may have about the strategy.

Brave testimonies by Canadian athletes such as Clara Hughes, Nadia Popov and Brittany MacLean as well as tragedies like the suicide of university basketball player Alex McLaughlin shed light on the fact that mental health challenges happen to athletes too. Athletes, coaches and support staff have unique needs, demands, pressures and expectations that they must effectively manage daily. However, this can be challenging to do. And that can lead to diminished well-being and overall health in the presence of high stress that is paired with underrecovery as well as a lack of both support and help-seeking (Gouttebarge, 2019; Reardon et al., 2019).

We all know that health is an essential ingredient for success in sport. So why has it taken so long for the mental dimension of sport participants’ health to be given the attention it rightfully deserves? After all, everything starts in the brain. And if the brain isn’t firing optimally, it jeopardizes sport participants’ ability to reach consistent high-level performance (Reardon et al., 2019). Physical injuries have typically been treated without question and without stigma in sport. It’s time for the sport community to do the same for mental injuries. With the brain playing a role in all bodily functions (controlling organs, thoughts, emotions, memory, speech and movements), individuals with reduced mental functioning must get the same compassionate care and support that’s traditionally been given for decreased physical functioning.

But it isn’t easy to change attitudes, behaviours and culture in sport. To provide a compass for this process, it’s essential to develop a national strategy that takes into consideration available scientific evidence, best practices around the world, and nuances of the Canadian context. Every stakeholder must be part of the solution and strive toward the common goal of promoting and protecting mental health in sport, using a clear and relevant roadmap.

This article introduces Canada’s tool to do so: the Mental Health Strategy for High Performance Sport in Canada, “the strategy” (Durand-Bush & Van Slingerland, 2021). This article provides an overview of how and why we developed the strategy. It also lists ways that sport leaders can begin to implement aspects of the strategy. It concludes with a list of frequently asked questions including responses and links to multiple resources. With this information, we hope that stakeholders at all levels of the Canadian sport system will answer the call to integrate mental health in their strategic plans and practices. We also want them to appreciate the mounting evidence that mental health is a key performance factor in reaching the podium.

“The resources need to be more readily available and clearly laid out as to what they are, where they are and how to access them. This isn’t just about stigma, it’s on many different levels. It’s a major issue in Canada … I want the help I had available to me, the support that allowed me to get through that and go on to do some really, pretty incredible things in my life that I continue to pursue, to be there for everyone.”

Clara Hughes, 4-time Olympian speaks with CBC Sports about her experience with depression

Developing the strategy

In July of 2018, a group of Canadian sport leaders (the ‘Mental Health Partner Group’) representing Own the Podium (OTP), the Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport (CCMHS), Game Plan, and the Canadian Olympic and Paralympic Sport Institute Network (COPSIN) began to lay the groundwork to develop the strategy (Durand-Bush & Van Slingerland, 2021). The primary aim of the strategy is to improve mental health outcomes for all Canadian athletes, coaches, and staff. Establishing and officially launching the strategy in July 2021 was the culmination of several years of research, consultation and teamwork, with careful consideration of the Canadian sport context.

The project was carried out by many stakeholders across Canada forming 4 different groups:

- The Mental Health Partner Group gathered foundational data and provided guidance, direction and oversight of the strategy.

- The Mental Health Expert Group developed the strategy’s content, based on scientific evidence and professional expertise.

- The Mental Health Reviewer Group reviewed the strategy and provided input based on scientific evidence and professional expertise.

- The Sport Community Group provided input on needs and gaps before developing the strategy and gave feedback after it was developed.

Understanding the strategy

The strategy’s underlying premise is that athletes who are mentally healthy are more likely to consistently perform at the highest levels in sport and continue contributing to sport after retirement. Also, athletes are more likely to reach their full potential and achieve success if coaches and staff are mentally healthy too. Therefore, in addition to focusing on athletes, the strategy also focuses on key leaders in the sport context, who are supporting athletes across their career.

Both mental health and mental illness must be considered to fully understand functioning and performance across the lifespan. Mental health is a state of psychological, emotional and social well-being. In that state, individuals are capable to feel, think and act in ways that allow them to enjoy life, realize their potential, cope with the normal stresses of life, work productively and contribute to their community (World Health Organization, 2018).

In contrast, mental illness (ill-being) is a health condition characterized by alterations in individuals’ feeling, thinking, and behaving that lead to significant distress and impaired functioning in their personal and professional activities. Mental illness refers to all diagnosable mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, schizophrenia, eating disorders and substance use disorders (World Health Organization, 2010; Mood Disorders Society of Canada, 2019). Priorities in the strategy target mental health promotion as well as mental illness prevention and treatment. Importantly, everyone can play a role in creating the proper environment in which sport participants can thrive and obtain adequate services and resources when they’re struggling.

Another vital component of the strategy is mental performance. Mental performance is the capability with which individuals use cognitive processes (that is, attention, decision-making, perception, memory, reasoning, coordination) and mental or self-regulation competencies (that is, knowledge and skills) to perform in their changing environment. Examples of mental performance competencies include goal-setting, planning, motivation, self-confidence, control (arousal, emotional, attentional), imagery, resilience, self-talk, stress management, communication, leadership and evaluation (Van Slingerland, 2019). Mental performance is key for bolstering mental health and buffering against the risks of mental health challenges and illness.

Actioning the strategy

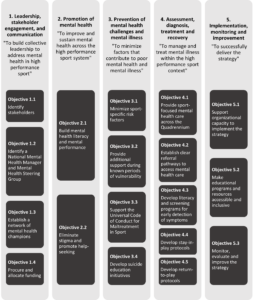

The aspirational strategy includes 5 priorities (see figure 1). Each priority is outlined with clear objectives, background information, and recommended actions to guide stakeholders. For the strategy to be successfully implemented and lead to sustainable positive mental health outcomes, then engagement, communication and alignment are needed. They’re required right across the entire sport system, from Sport Canada, Multi-Sport Service Organizations (MSOs), and National and Provincial/Territorial Sport Organizations (NSOs and PTSOs) to coaches, support staff (for example, Mental Performance Consultants [MPCs]) and athletes.

It will take time and resources to address all aspects of the strategy. However, the Mental Health Steering Group created to oversee the strategy has already undertaken some actions to guide and support the high performance sport system to implement the strategy. For instance, Game Plan hired a national Mental Health Manager who, with the support of the CCMHS, formed a national Mental Health Network of vetted mental health practitioners with high performance sport knowledge, experience and expertise. A Mental Performance Ally Network, consisting of MPCs who can work in collaboration with mental health practitioners, has been created too. Other short-term actions stemming from the strategy include identifying COPSIN, NSO, and MSO points of contact, defining clear referral pathways to access mental health care, and developing and delivering fundamental educational programs across the sport ecosystem to increase mental performance and mental health literacy.

Worldwide, Canada is now 1 of only 2 countries with a comprehensive national mental health strategy for high performance sport and a national mental health steering group that includes a national mental health manager. Canada also has a strong and vibrant community of MPCs. They play an active role in promoting and nurturing mental health within the sport community, and collaborating with mental health practitioners when challenges and illness arise. There are currently 200 MPCs who are professional members of the Canadian Sport Psychology Association. Of those members, 32 of them have a dual credential of MPC and clinical or registered psychologist or counsellor. Given the rise in Safe Sport issues reported in Canada and the rest of the world, it’s crucial for sport leaders to hire legitimate MPCs who: (a) have adequate education and training, (b) have adequate professional and ethical practice competencies, and (c) are in good standing with the Association (see requirements here).

| Did you know? |

| The Canadian Sport Psychology Association (CSPA) is an organization that oversees the practice of mental performance in Canada. One of its mandates is to assess and list Mental Performance Consultants (MPCs) who meet minimum requirements to provide mental performance services in Canada. The CSPA also recognizes MPCs who are dually trained as licensed and registered mental health practitioners (that is, psychologists, counsellors, psychotherapists, social workers; Durand-Bush & Van Slingerland, 2020). |

What NSO leaders and staff should know

NSOs may initially feel overwhelmed, even though the strategy is an incredible roadmap to improve the collective well-being of sport system participants. Leaders may wonder where to begin and how to make an impact in the mental health space, given their own limited financial and human resources. As the Mental Health Manager with Game Plan, part of Dr. Krista Van Slingerland’s role is to support organizations and individuals within the system to implement the strategy as well as mental health programs, initiatives, and resources more generally. Below, Dr. Van Slingerland answers frequently asked questions about the strategy.

- What mental health supports exist for athletes within the high performance system?

Athletes have access to both general and sport-focused mental health support that is free of charge or subsidized by Game Plan. These include:

- Lifeworks: Athletes can access free support through Game Plan’s mental health partner, Lifeworks. Lifeworks offers a helpline that’s available 24 hours per day, every day of the week, short-term counselling, self-directed mental health programs, group therapy, and several mental health maintenance tools to help athletes stay healthy.

- Sport-focused mental health support: Athletes have access to $1000 per year to help subsidize costs for mental health services provided through the Mental Health Network (MHN) and the Canadian Centre for Mental Health and Sport (CCMHS). Learn more about the funding. This support gives athletes access to more than 70 trusted mental health practitioners across the country who have experience, knowledge or training in sport. Athletes can access the MHN and CCMHS by emailing the fully bilingual Mental Health Network Coordinator at mentalhealth@mygameplan.ca.

A summary of the subsidized supports available to athletes are shown in an infographic titled, Pathways to mental health support.

- What mental health supports exist for coaches and NSO staff within the high performance system?

Coaches and NSO staff can access Lifeworks’ services free of charge. This is the only coverage currently available to them through Game Plan. Coaches and staff could be directed to a mental health practitioner through the MHN or CCMHS, but these services aren’t covered by Game Plan.

- Where can NSO leaders and staff find resources to help them address mental health in their organization?

Resources for NSOs can be found in the NSO Sharing Centre hosted by the Canadian Olympic Committee. Here you’ll find tools and resources such as a Needs and Gap Assessment Tool to assist NSOs in integrating mental health into their strategic plan, and one-page fact sheets with information about how mental health intersects with a number of priority areas within sport such as performance, maltreatment, and risk management. If sport leaders are interested in getting updates on mental health straight to their inbox, including new tools, resources and workshops being offered to athletes, coaches and support staff, they can join the mental health mailing list.

- As an NSO with limited human and financial capacity, what can I do to address mental health?

To make an impact in the mental health space, it isn’t necessary to have a mental health strategy specific to your sport, or an embedded mental health practitioner within your IST. There are easier and cheaper ways to begin to address mental health, including:

- Consistently and frequently communicating what mental health supports are available at no cost or subsidized cost to athletes, coaches and support staff, including crisis resources.

- Encouraging athletes to engage with their Game Plan Advisor. Game Plan isn’t just a career transition program. Game Plan programs and resources (for example, access to educational and skill-building opportunities) can contribute to promoting mental health and preventing mental illness and mental health challenges at the athlete level.

- Continuing to work with MPCs. Registered MPCs can assist your organization in optimizing its sport culture to support well-being and performance, contribute to athletes’ mental health maintenance, and ensure you know when, where, and how to refer individuals who may be struggling with mental illness.

- Scheduling regular mental health check-ins with athletes. Mental health check-ins allow for early identification of mental health challenges and mental illness. The International Olympic Committee suggests using the Athlete Psychological Strain Questionnaire as a first step triage tool. This 10-item questionnaire isn’t diagnostic, but rather flags to practitioners the potential mental health challenges. The questionnaire can be administered by MPCs, sports medicine physicians, or other health professionals working with teams.

- Ensuring athletes, coaches and support staff are aware of the Canadian Sport Helpline, its purpose, and how to access it.

- Encouraging athletes, coaches, and support staff to complete mental health literacy and Safe Sport training. Game Plan will be delivering a series of free mental health workshops (nationally and via COPSIN) for high-performance athletes, coaches, and support staff. Sign up for the mental health mailing list to take advantage of these opportunities.

To further develop your organization’s approach to mental health, consider working through the Needs and Gaps Assessment Tool for sport leaders.

- Is it necessary to embed a mental health practitioner within our IST?

It’s unnecessary to have a full-time or part-time mental health practitioner embedded within your IST, and this isn’t a recommendation in the strategy. Given empirical evidence and feedback from the sport community (such as, athletes, coaches, support staff), Game Plan opted to support a “network” approach to mental health service provision. This way athletes may choose a mental health practitioner who is a good fit for them. The network approach also removes barriers to seeking help (for example, fear that seeking help through NSO structures will impact athletes’ career). Lastly, it assumes the financial and administrative burden of vetting practitioners, assessing athletes’ symptoms, collecting consistent aggregate (anonymized) data, matching athletes with an appropriate practitioner, and administering payment to providers.

Hiring a mental health practitioner to provide care within your NSO could facilitate contextual knowledge, accessibility to care, and collaboration within the IST. However, many athletes report that they prefer to seek care via the MHN or the CCMHS to maintain anonymity and confidentiality. Mental health practitioners must respect several regulations (see the Personal Information Protection and Electronic Documents Act; the Personal Health Information Protection Act; and the Mental Health Act; the Child, Youth and Family Services Act). So, fully integrating practitioners into teams or sports could pose challenges. Furthermore, this would represent a duplication of some costs and structures that have been put in place at the national level, dollars that could be redirected within your organization. Contracting a mental health practitioner or a dually certified MPC to deliver, contribute to, and support the mental health programming and resources being developed at the national level would arguably be a more efficient use of dollars directed toward mental health.

Summary

The strategy exists to ensure that the sport system has a long-term plan and adequate funding to equip athletes, coaches, and support staff with appropriate knowledge, skills and support to manage their mental health and thrive throughout their career. NSO leaders and staff wishing to further understand and improve how they address mental health, please contact Dr. Van Slingerland for assistance:

Email: kvanslingerland@mygameplan.ca

Phone: 647 619-2654