Highlights:

- 2 Loops Theory of Change seeks to describe and model organizations as living beings with life cycles

- Indigenous sport leader, Dorothy Paul, advocates for 2 Loops Theory as a lens to consider cultural shift within the Canadian sport sector

- In this SIRCuit article, SIRC interviews Paul to gain her perspective on cultural change, pressing issues and system shift

Dorothy Paul has several decades of experience as an athlete, mentor and facilitator within sport in Canada. But organized sport wasn’t always a part of her life.

“Growing up, I was the oldest girl of 7 kids, so there wasn’t a lot of extra money for me to participate in sport,” she says. Paul would play outside with her siblings, climbing trees and racing, jumping from tree to tree.

Things changed after Paul and her siblings watched the Montreal Olympics in 1976. The Olympics inspired new versions of their old games: “We created an obstacle course around the house using saw horses, jumping over the septic tank, all kinds of things. And we would race to see who could do it the fastest. And I guess it accidentally trained me well for middle school cross-country!” Paul says.

Middle school cross-country led to high school track, soccer, field hockey and rugby, which then led to an over 30-year career in the Victoria Women’s Premier Soccer League. Now, Paul is a master facilitator for the Aboriginal Sport Circle’s Aboriginal coaching modules and has served as an Indigenous Long-Term Participant Development Pathway mentor through Sport for Life. She has held several positions with the North American Indigenous Games, including serving as the Chef de Mission in 2002.

After retiring from soccer, she started a women’s box lacrosse team, the Victoria Wolves, which she still plays with. But when the world shut down with COVID-19 and Paul had a little extra time to reflect, she started thinking about how the sport system needed to change, and searching for models of what that could look like.

“For 30 years, I’ve been hearing people say, ‘We need to un-silo, we need to un-silo, so what are we not doing? What’s preventing us from un-siloing?’ Maybe we need to take a different look at systems change and possibly that will spark conversations with people and then they’ll start to do things just a little bit different,” Paul says.

In doing so, she came across the 2 Loops Theory of Change.

Exploring 2 Loops Theory of Change

2 Loops Theory of Change was developed through the Berkana Institute (established in 1992) and specifically an article published by Margaret Wheatley and Deborah Frieze entitled “Using emergence to take social innovation to scale.” The theory seeks to describe and model organizations as living beings with life cycles, rather than as mechanistic entities that are unchanging.

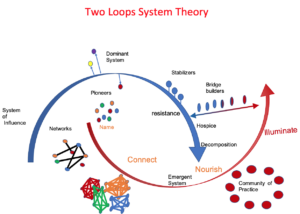

The theory depicts the processes involved in the transition from one system (the dominant system) to another system (the emerging system). Within and between each system, people take on a variety of roles, including as:

- Pioneers: The people who recognize a system needs to change and start looking for alternatives, eventually forming networks that lead to a new emerging system

- Stabilizers: Those who acknowledge the emerging system, but understand that change takes time, and will help with the transition

- Resisters: Those who are resistant to change within the dominant system because it serves and benefits them or they feel they don’t have a role within the new system

- Bridge builders: Those who help people move from the dominant to the emergent system

- Hospice workers: Those who wind down the dominant system and redistribute the resources into the emerging system

The theory accounts for the fact that you are both an individual and a member of a system. It also accounts for the fact that change isn’t linear, life’s external forces impact how a system operates, hence why a system can never really remain unchanged.

This is what originally drew Dorothy Paul to the theory, and what made her start thinking about the potential for using it as a model to inspire reflection and change within the Canadian sport sector.

“It’s fluid,” Paul says of the 2 loops model, “It’s not concrete. Other systems theories I saw came at it from like a mechanical point of view, where it’s like, ‘Oh, this piece isn’t working? Let’s take it out and replace it with something else and oh, why didn’t that work?’ [Those models] have forgotten that all the pieces of a system rely on all of these other things to exist as well. I like the idea of systems change from a human point of view and a fluid point of view.”

In their original article, Wheatley and Frieze (2006) write: “Despite current ads and slogans, the world doesn’t change one person at a time. It changes as networks of relationships form among people who discover they share a common cause and vision of what’s possible. This is good news for those of us intent on changing the world and creating a positive future. Rather than worry about critical mass, our work is to foster critical connections.”

Almost everyone is familiar with the idea of growth within a system or sector. What we don’t often talk about is the decline of an organization, system, or sector. Decline is not necessarily failure, it may just mean that the context in which the system exists has changed, and now a different system would be better suited.

Frieze uses the example of the oil industry. We are all likely familiar with oil’s rise to be the dominant system. As people learned more about pollution, climate change, and fossil fuels, individuals began questioning the system and looking for alternatives. In the 2 loops theory, these people are called pioneers. These pioneers truly gain strength when they begin to connect with each other, forming networks and brainstorming new systems. This occurs at the same time as those resisting any change from the dominant system are saying things like: “we’ve always done it this way,” or “we’re too big to fail.”

System change isn’t flipping a switch. And dominant systems are not inherently bad. They often have important elements to carry forward or learn from. This is why the roles of “stabilizers” and “hospice workers” are important. They are the people within the dominant system that recognize that change is coming, and work to help the older system transition into the new. In the oil industry example, they are not only the people thinking about how infrastructure can switch from oil and gas to renewable energy, but also the people that consider what will happen to people currently employed by the oil industry and helping to figure out how to transfer their skills elsewhere.

These roles are important because there’s always a gap between dominant and emergent systems, this is why in the diagram itself, the loops don’t touch. The emergent system isn’t ready to catch and carry everyone from the dominant system right away. The old system needs to be gently wound down in a respectful manner, with its resources redistributed and lessons learned carried forward. Bridge builders are the people that help everyone transition from the dominant to the emergent system. At which point, the lifecycle of the system starts again.

A conversation with Dorothy Paul

Paul has presented to different audiences in the Canadian sport sector, using 2 Loops Theory to suggest a pathway for change and instill reflection within individuals and organizations. SIRC chatted with Paul to dive deeper into some of her thoughts on our changing sport landscape.

SIRC: What do you think are the most pressing issues that we’re facing as a sport sector right now?

DP: Our current sports system is based on volunteerism. With COVID, volunteerism has almost disappeared. So either our system is going to have to really adapt or we’re going to have to really look at ways of restructuring things, how we do things at the community level, at the provincial and territorial sport organization level because we’re not going to have people to train athletes to move through the system and we’re not going to be able to pull our coaches, our administrators from the system of volunteers as we have been. I don’t know what the answer is for that, but I think we need to consider: how did other countries make that transition? And what did they do to make that transition? Because I think in Canada we aren’t going to rely on volunteerism much longer.

Even though this is kind of an older change theory, I think it still has value because it takes into account all the outside influences. In the last little while because all of the things that have been happening in the media, like Safe Sport, diversity and equity, those things have really been pushing the current system and have been at the forefront for the past 4 or 5 years. Which is why I think we’re somewhere here [points to the middle of the 2 loops, during which a dominant system is transitioning through hospice and decomposing, and another system is emerging on its way to communities of practice].

For example, the system has created courses for people to take to ensure that we understand as coaches and as workers in this system that we’re educated on these things that are coming forward and pushing our system in an emerging direction. But for the volunteers that are coming through, they’re thinking: “I just want to coach right now, but now I have to do Safe Sport workshops and coaching workshops, and a criminal record check! Do I really want to spend 3 weeks to become a coach for a 4-month season?” We have to recognize that when you get down to the community level, sometimes volunteers don’t want to spend that much time, they just want to go and coach. So with the Rule of Two, Safe Sport and all of the other courses that have cropped up in the last 5 years, people are hesitant or walking away from wanting to participate in the sport system. I’m also seeing a lot of movement within sport administrators, a high turnover in organizations. Which makes me think that we could still be here [points to left side of model with pioneers leaving the dominant system].

SIRC: How can we use the 2 Loops system to think about that problem?

DP: I think we need to pay attention to how we’re treating people in the system. The people who are part of the resistance, or the stabilizers, or the hospice, that takes a lot of time and energy. We need to be really understanding: “What does this employee in front of me bring to the table and what are their real strengths? Does the position we put them in actually suit how their brain works?” When people are in a position where it’s a great fit for them, they’re going to do all kinds of work.

What I’ve seen in the system today, really, is if you’re not working 100 hours a week, you’re not producing, so therefore you’re not valuable to us. That’s not sustainable. I think COVID got a lot of people thinking, “do I really want to consistently do 100 hours a week for a system that views me as expendable?”

So, it’s really looking at how we can keep the good people that are in our system and support them so that they want to stay for a longer period of time. I’m even thinking even just in mainstream sport [as opposed to Indigenous], it’s harder and harder for people to be an employee for life. People come in, they’re employed in one area for 3 to 5 years and then they move on to something else. What do we need to do as employers within the system to ensure that our employees feel supported and valued?

The current system as it is feels safe, the “this is what we know, therefore we’re going to keep doing it.” So now it’s a question of how do we share new information in such a way, like with all the Safe Sport programming, where we can translate it into our place of employment, our administration, our organization? That’s where we need those stabilizers, bridge builders and hospice workers.

SIRC: What’s the response been like from when you’ve done presentations on 2 Loops within the sport sector? Does it resonate with people?

DP: One of my presentations, I physically made the loops with rope and asked people to stand on where they thought they fit in the system. Nobody wanted to stand on a dominant system because of the type of conversation we had around that. But there’s a reason we need those dominant people.

I like the terms dominant and emerging instead of new and old systems because “new” implies that the old is bad, but it’s not. As the system is changing, we need to figure out which are the parts of the dominant system we are going to keep because not everything is terrible in the current system, and there’s a lot of good things in there. And that’s what the hospicing and decomposing is about.

More than half of people went to bridge building, which really says something about how people are registering change in the system.

SIRC: What else is important to keep in mind when using this model to think through change in the sport system?

I think for me what keeps coming up is thinking through that decomposition piece. There’s a lot of good things in this current system. We need to take a hard look at what actually needs to change. For me, it’s the human element. That’s my biggest piece, how are we treating our people within this system? And how can we keep them? It bothers me that I’ve come across a fair number of people who have just left the system altogether and gone elsewhere. That person had a huge set of skills and had a huge history of the sports sector. How come we couldn’t keep them? How come we couldn’t shift them into a different role?

So when we think of the dominant system, we can’t just think of the people that are in it as the resistance. We need to find a way to address that resistance and share where that new system is actually moving, what it believes in, and how they are a valuable part of that emerging system, that they do have a role to play.

Questions for sport orgs and individuals to consider:

- Imagine someone drew the 2 loops chart on the floor: where would your organization fall? What about you as an individual?

- What external pressures are there on the sport system in Canada?

- What countries can we look to with positive emergent systems? How have they transitioned? What do we admire about their systems?

- What do we need to learn from the dominant system to take forward into the emergent system (decomposition and redistribution of resources and knowledge)?

- What role do I play within the system? Am I a pioneer, stabilizer, resistor, hospice worker, bridge builder?