Highlights

- Despite its status as an Olympic city, attitudes towards sport and recreation initiatives in Calgary have been mixed.

- A city’s active economy includes all organizations and individuals who directly or indirectly contribute to the development and delivery of sport and active recreation experiences.

- Calgary’s active economy includes 95% of the 1.5 million people living in the Calgary region, incorporating 4000 enterprises, employing 43 000 people, and contributing $3.3 billion to the regional economy.

- The ActiveCITY Collective is a collaboration of not-for-profit, for-profit, and public-sector organizations as well as individuals engaged in Calgary’s regional active economy. It was created to leverage Calgary’s active economy for regional growth and prosperity.

- ActiveCITY Collective’s Playbook 2030 aims to establish a framework to maximize the impact of Calgary’s regional active economy on both individual and community well-being, and in doing so, transform Calgary into Canada’s most livable region.

In November 2018, Calgarians participated in a plebiscite to decide if the city should proceed with a bid to host the 2026 Olympic and Paralympic Games. Calgary’s shot at hosting its second Olympics and first Paralympics came to an end as 56.4% opposed bidding. This was perhaps the final straw in what we, Calgary-based academics at Mount Royal University, had seen as a trend: sport and recreation were being minimized and underappreciated in Calgary.

Another example was the ongoing debate and public pushback about whether Calgary should fund a field house, a conversation that started in the 1960s. Calgary is the only major Canadian city without such a facility. Other examples included the moral outrage over the expansion of separated bike lanes, the city considering closing public golf courses, and WinSport shuttering the bobsled, skeleton and luge run, a legacy track of the 1988 Olympic Games.

The past few years have been volatile for Calgary’s sport and recreation sector. Every week, it seemed, we debated and questioned our commitment to being a city that promoted and supported an active life. We considered Calgarians as members of an Olympic city, one that embraced, celebrated and aspired to lead in sport and recreation, as well as health and wellness. But was this still true?

Defining a ‘great sport city’

In January 2019, we assigned a question to undergraduate students who were studying sport and recreation management: Is Calgary a great sport city? We gave students latitude in how they defined a great sport city, with ideas ranging from the number of fans attending professional sport events to the number of world-class events hosted by the city. Students presented their findings to local sport leaders at the Canadian Sport Institute Calgary. When asked to rank Calgary against these findings, the results of the student analyses were mixed. Despite its status as an Olympic city, Calgary fell in the middle of most rankings.

After further considering this question, we gathered 50 sport leaders from Calgary and the surrounding area for (what we called) the Sport Business Roundtable, in the Mount Royal University library. Delegates were from grassroots clubs to high-performance sport, including representation from ski hills, eSport, and postsecondary athletics and recreation. We spent the morning debating the future of sport. This included a welcoming plea from City Councillor and mayoral candidate Jyoti Gondek asking the sport community to provide a meaningful business case for why taxpayers should support and engage in sport.

Three takeaways emerged:

- We concluded that “sport business” was the wrong term to describe ourselves. We collectively decided to start using “active city.”

- The people we invited didn’t really know each other. We had assumed they would already know one another.

- This group genuinely wanted to connect and collect, which was reaffirmed when most delegates stayed well past the session’s ending time. And lunch wasn’t even provided!

From this meeting, we concluded that Calgary’s rich regional active ecosystem was fragmented and inefficient. The result was its contribution to Calgary’s economic, human, social and environmental prosperity was being underleveraged.

The ActiveCITY Collective

The response was to create the ActiveCITY Collective: a collaboration of not-for-profit, for-profit and public-sector organizations as well as individuals engaged in Calgary’s regional active economy. Our goal was to transform Calgary into Canada’s most livable region through its active economy, and do this by facilitating collaboration, debate, learning and connection. The Collective would need to be independent and inclusive. It should be anchored in a systems perspective and work towards generating community prosperity. Finally, the Collective must use evidence and not anecdotes.

The ActiveCITY Collective was built upon the idea of an active economy that was grounded in 2 models. First, the New Zealand Model of Community Prosperity (also known as Living Standards Framework), which recognizes that benefits can be felt in the human, economic, environment and social spheres (New Zealand Treasury, 2018). The second model was Dr. Richard Florida’s idea of a creative class. In the early 2000s, Florida noted that “Beneath the surface, unnoticed by many, an even deeper force was at work—the rise of creativity as a fundamental economic driver, and the rise of a new social class, the Creative Class” (Florida, 2002). Could a similar argument be made about an active economy? Could Calgary and region mimic the growth of cities such as Nashville, which hung its hat on the idea of a creative class?

Nashville wasn’t an accident. Its creative ecosystem was built and nurtured for more than 100 years. It harnessed all its resources, from universities to musicians to entrepreneurs, to build a city and region that would attract and retain the best and the brightest. In 2006, Nashville included 80 record labels, 100 music publishers, 150 recording studios, 17 of the top 25 country music artists, and 39 fully integrated collaborative organizations (Raines & Brown, 2006). Could Calgary and region do the same thing but from an active economy lens?

Therefore, we began the process of trying to map and understand the breadth and depth of the active economy.

Mapping the active economy

The process of mapping the active economy included a series of steps that started with the creation of categories of organizations. This was followed by groupings of individual participants and concluded with a mapping of their interrelationships.

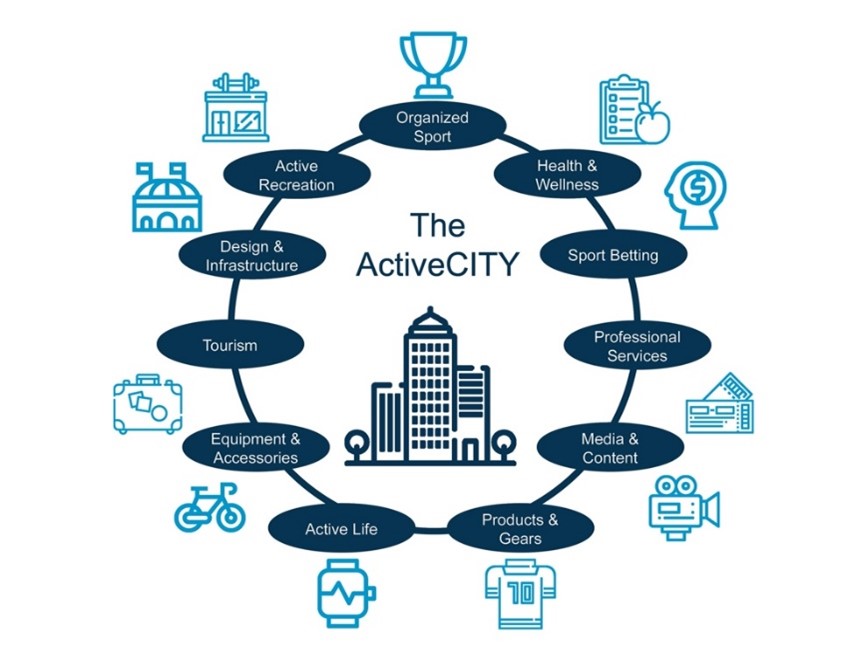

The first step was to create groupings that would enable measurement and a better understanding about what types of organizations constitute an active economy. We created 11 categories including organized sport, health and wellness, sport betting, professional services, media and content, products and gear, active life, equipment and accessories, tourism, design and infrastructure, and active recreation.

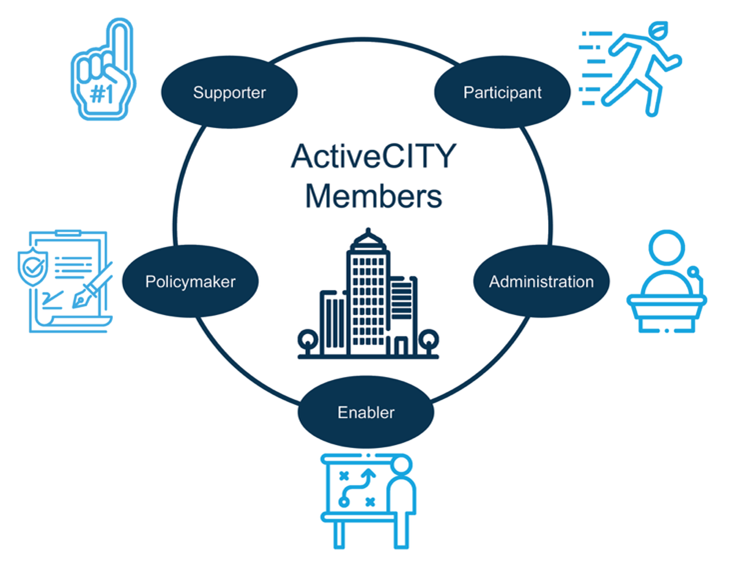

The second step was trying to understand the people in the active economy. Every individual or organization with an interest in or impacted by the active economy was considered an important player. This includes all forms of engagement, including professional or volunteer. Therefore, the ActiveCITY Collective defined engagement in 5 categories: participant, administration, enabler, policymaker and supporter. An individual or organization may encompass one or more forms of engagement.

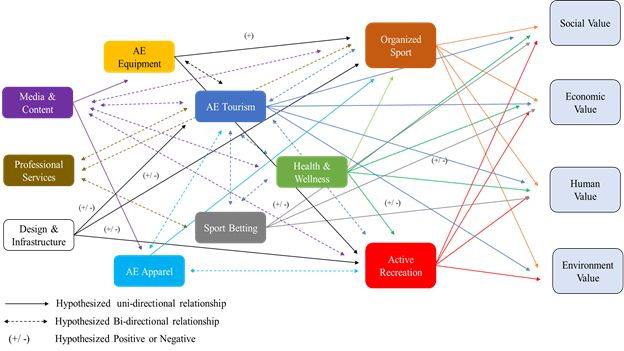

In the third step, we attempted to map the interrelationships of the various factors of the active economy. The categories that we noted earlier didn’t operate in isolation. The potential benefits from the active economy would require interrelationships among the categories. While conceptual, our map showed the series of hypothesized links between different aspects of the ecosystem. For example, environmental value can be gained through the connections from design and infrastructure through active recreation. While complex, this map was central to our understanding of where and how to allocate resources that would generate maximum return on the public’s investment. This was answering City Councillor Gondek’s call for action at the Sport Business Roundtable.

During the mapping phase, we cajoled and recruited a broad cross-section of leaders in which to debate, discuss and consider how the sector could better work together. Due to overwhelming interest from would-be participants in the lead-up to a fall 2019 summit, the venue had to be changed 3 times! The summit was eventually held at WinSport with 300 participants and a waiting list.

Clearly, the idea of an active economy had struck a nerve. After launching an ActiveCITY website, we began to measure the active economy through research. With a team of students and colleagues, we enacted Calgary’s largest public engagement strategy, collecting input from more than 23 000 individuals. In addition, we hosted 20 virtual ‘FutureMaking’ Forums on topics ranging from eSport to First Nations and Indigenous persons in the active economy. We recorded more than 25 podcasts with community leaders discussing the future of Calgary’s active economy. We also helped coordinate province-wide longitudinal research on the intersection of arts, culture, and sports and recreation in a pandemic and post-pandemic environment. We determined that the active economy includes 95% of the 1.5 million people living in the Calgary region, incorporating 4000 enterprises, employing 43 000 people, and contributing $3.3 billion to the regional economy.

This led to the creation of Playbook 2030 and provided direction for Calgary’s support of the active economy.

From pandemic to Playbook 2030

The impact of COVID‑19 can’t be understated. The pandemic is causing seismic economic, human, and social costs to our city and region. Since travel and large gatherings are restricted, our outdoor recreation facilities face unprecedented capacity pressure. This has only accelerated the urgency of creating an integrated master plan for our regional active economy. The resulting master plan is known as Playbook 2030. It’s anchored in a strategic framework that will harmonize resources from across the commercial, social, and public sectors to strengthen our economic, human, social, and environmental prosperity. While Calgary is facing unforeseen challenges, Playbook 2030 identifies unrealized opportunities and unique advantages. The time is right to deliver a renewed vision of our city and region that leverages our greatest natural resource, an active economy.

We presented Playbook 2030 to the community during a virtual online summit on December 2 and 3, 2020. The theme was From Pandemic to Playbook 2030. At the summit, we reviewed the path from the devastation of COVID‑19 to the vision of a world-leading active economy as detailed in the Playbook.

In the press release following the summit, Cynthia Watson, the newly named co-chair for ActiveCITY and Chief Evolution Officer of Vivo for Healthier Generations, noted that “Calgarians challenged us in November 2018 to think differently. They wanted us to look forward, not backward. With the guidance of thousands of Calgarians and insight and inspiration from global leaders, we have defined a city that is not only a player, but a leader in the $3 trillion active economy.”

The Playbook 2030 plan was based on 6 pillars: a shared vision, embedded in life, built on community, innovate and grow, drive sustainability, and inspire others. The plan also returned to the New Zealand Model of Community Prosperity, including links to the human, social, economic, and environmental impacts. For example, under economic impact we referenced a study for the British Columbia Ministry of Health Planning that estimates an annual cost savings of $49.4 million if physical inactivity could be reduced 10 percent.

Conclusion

We’ve attempted to create an ActiveCITY that is inclusive. It brings together volunteers, coaches, entrepreneurs, educators, policymakers, parents and guardians, in areas ranging from tai chi and gardening to soccer and emerging sport technology. What we share is a passion for the unique role that the active economy can play in moving our city and region forward.

For other cities and regions attempting to mirror this process, we offer the current steps being taken to implement our Playbook. The first is to transition the ActiveCITY Collective into a more formal structure. The second is to establish a harmonized governance model for implementing the program. The third step is to deliver a few quick wins with research studies showing benefits of how collaboration has worked. And the final step is to prioritize high-impact, ecosystem projects for Playbook 2030.

To support the implementation of Playbook 2030, the ActiveCITY collective has received a 2-year grant from the Government of Alberta’s Civil Society Fund. The goal of Playbook 2030 is to establish a framework to maximize the impact of Calgary’s regional active economy on both individual and community well-being, and in doing, transform Calgary into Canada’s most livable region. At times, the scope and depth of Playbook 2030 may feel daunting. For this reason, we think it is best to consider Playbook 2030 as a critical step in a ten-year master business plan for Calgary’s regional active economy. As a complex $3.3 billion business that incorporates 4000 enterprises across 10 sectors and impacts 1.3 million people, the business plan must be systematic, rigorous and evidence-based.

Playbook 2030 is uniquely Calgary. Its approach combines academic rigour, community spirit, entrepreneurial optimism, and a belief that this is a promotable differentiator that defines our civic culture and identity for a generation. We’re facing challenges unforeseen and unprecedented. This is a necessary and opportunistic time to be contemplating a new vision for our city and region, based on collaboration and leveraging our greatest natural resource, our active economy.