An essential part of improving sport service delivery is program evaluation. Program evaluation allows sport organizations to understand how their programs or initiatives work in different ways. However, many organizations receive insufficient training or lack the capacity (staff, funding or time) to engage in evaluative work (Carman & Fredericks, 2010).

One way that sport organizations can boost capacity for evaluation is to involve students and volunteers. Indeed, there are many examples of graduate students partnering with sport organizations to evaluate programs as part of fulfilling their degree requirements. These include evaluations of the True Sport Foundation’s initiatives (Lawrason et al., 2021), Golf Canada’s youth programs (Kendellen et al., 2017), and the Girls Just Wanna Have Fun program for improving life skills (Bean et al., 2014). Research shows that volunteers can also play an important role in providing evaluation support (Rosso & McGrath, 2017).

This blog presents examples of how students and volunteers have engaged in and built capacity for evaluations that support the Canadian sport and physical activity sector. This blog also shares lessons learned.

The benefits of involving students and volunteers

Including students and volunteers in program evaluations has several benefits for sport organizations. For instance, graduate students may have knowledge of frameworks and tools to guide evaluation practices and have the training to produce rigorous and evidence-based results for the sport organization. Additionally, students have access to research papers that are typically behind paywalls for the public, which may help to facilitate specific evaluation methods, such as the use of validated questionnaires.

On the other hand, volunteers are likely to have an intimate knowledge of how the organization functions, including lived experience. Volunteers can also helps organizations to build capacity by increasing the likelihood that they will remain in the organization. Finally, by having volunteers conduct program evaluations, organizations are using their available human resources as effectively as possible.

Lesson 1: Invite, involve and build capacity in students and volunteers

Students are essential to community-research networks. They often lead projects and complete on-the-ground work like relationship-building, data collection and analysis, and writing reports. This provides students with opportunities to expand their skills and connections beyond academia. As a result, students play a key role in building capacity for knowledge translation with community partners.

Volunteers, too, are well-positioned to undertake evaluations in community-research networks. More than one million Canadians volunteer in sport organizations (Doherty, 2005). Although most sport volunteers spend their time coaching (60%) or supervising activities and events (71%), there is significant room for volunteers to conduct research and evaluation activities, especially during the pandemic. Much of the evaluation work can be completed online, and virtual volunteering is becoming increasingly popular while social distancing is required.

Example: The Canadian Disability Participation Project

The Canadian Disability Participation Project (CDPP) is an alliance of university, public, private and government sector partners working together to enhance participation among Canadians with physical disabilities across employment, mobility, and sport and exercise sectors. The CDPP involves nearly 50 cross-sector partners that engage in community-based projects. This leads to resources and publications that partners can use and disseminate.

The Canadian Disability Participation Project (CDPP) is an alliance of university, public, private and government sector partners working together to enhance participation among Canadians with physical disabilities across employment, mobility, and sport and exercise sectors. The CDPP involves nearly 50 cross-sector partners that engage in community-based projects. This leads to resources and publications that partners can use and disseminate.

About 25% of the 239 individuals involved in the CDPP network are students. From 2014 to 2020, students accounted for 227 connections between 14 different researchers (and indirectly, community partners). This shows that students can play a significant role in how a network looks and functions and help to fill in the gaps where projects occur.

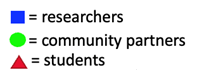

To demonstrate, each icon in the diagrams below represents a person in the CDPP. The line indicates a relationship or someone a person has worked with in the CDPP. The first diagram represents the CDPP network with only researchers and community partners, and without students. The second diagram represents the CDPP network with researchers, community partners and students (red triangles).

Without Students

With Students

For example, one student in the CDPP network completed an evaluation of teaching resources to promote inclusive physical education (Tristani et al., 2019). Since then, a knowledge translation bulletin containing strategies for inclusive education was developed for teachers.

Under the mentorship of academic and community leaders, students can build their evaluation skills to support organizations as they achieve their academic requirements. Involving students allows them to be prepared for post-graduate job opportunities in both the academic and non-academic sectors. Likewise, by equipping volunteers with opportunities and training to conduct evaluations for sport organizations, volunteers can enhance their roles as vital components of sport systems, contributing to the organization, governance and administration, and delivery of sport in Canada (Harvey et al., 2005).

Lesson 2: Leverage the diverse experiences and knowledge of students and volunteers

Students and volunteers come from diverse backgrounds and bring new perspectives to solve tough problems. They are excited to learn new skills and apply their efforts directly in the field. Encouraging students and volunteers to be leaders, be forthright and confident with their ideas, and explore different lenses for analyses can help sport organizations grow.

Reflection: My experience as a student partnering with True Sport

True Sport is a series of programs and initiatives designed to leverage the benefits of sport through a platform of shared values and principles. In 2018, I was part of a research team that partnered with True Sport to conduct a pragmatic evaluation of the True Sport initiatives (Lawrason et al., 2021). The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) Framework (Glasgow et al., 1999) informed the evaluation. The RE-AIM Framework provides a guide of what to evaluate in a program beyond effectiveness. Learn more about how the RE-AIM Framework has been applied in sport.

As a master’s student at Queen’s University, my role in the evaluation was to review literature about the RE-AIM Framework and how to conduct program evaluations with sport organizations. I was also responsible for collaborating with True Sport staff members to assess which questions were realistic to address and how to retrieve data. I then analyzed the data and delivered a report to True Sport regarding recommendations for the initiatives. We also wrote a manuscript and developed a template to help sport researchers and practitioners learn how to conduct evaluations.

One of the biggest challenges was adapting the RE-AIM framework for sport organizations. The RE-AIM framework was developed for evaluating planned, health interventions in research settings, not the dynamic world of sport. However, under the mentorship of my academic supervisors, I was able to shift my perspective and use the framework in non-traditional ways to support the evaluation with True Sport.

From this experience, I became passionate about conducting evaluations and working in partnership with communities to ensure research findings are impactful for end-users. True Sport was able to receive a list of recommendations for their initiatives and better understand how their organization works, such as its distribution of membership over time and resource allocations. Finally, True Sport also continued its partnership with Queen’s University to facilitate a knowledge translation conference to help bridge the gap between research and practice in the sport sector. I coordinated the conference and reported key findings with the goal of fostering community engagement in sport psychology research.

This example shows how student-led evaluations can lead to stronger partnerships, skill development and practical resources for sport organizations more broadly. Given their diverse backgrounds and experiences, volunteers can also aid in bridging the gap between communities and universities for the benefit of the sport sector.

Conclusion

While often overlooked or unused, students and volunteers can be great human resources for conducting evaluations in sport. To harness these resources, partnerships between sport organizations and researchers in university-based settings are a good place to start. Researchers can collaborate with sport organizations to invite, involve and build capacity with students and volunteers. Such collaborations also provide opportunities to leverage the diverse experiences and knowledge that students and volunteers can bring to the table, resulting in benefits for everyone involved.