Highlights:

- The first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation took place on September 30, 2021. This day honours the survivors of the residential school system, their families and their communities.

- Reflecting on truth and reconciliation in Canadian sport, this article explores mental health considerations for Indigenous sport participants.

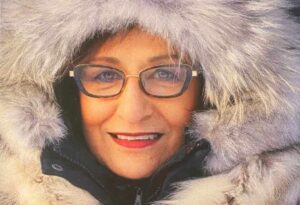

- SIRC sat down with Sharon Anne Firth, one of the first Gwich’in Indigenous women (alongside her twin sister) to compete in 4 winter Olympic Games, and Chantale Lussier, a mental performance consultant and Founder and CEO of Elysian Insight, mental performance solutions.

- We speak about the topic of mental health, Firth’s experience as an Indigenous athlete, and what truth and reconciliation mean for sport organizations and mental health and performance practitioners.

The first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation took place on September 30, 2021. This day honours the survivors of the residential school system, their families and their communities. Shortly after the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, SIRC had the opportunity to speak with Dr. Sharon Anne Firth. Dr. Firth is a residential school and Indian Day School survivor. She’s also among the first Gwich’in Indigenous women, alongside her twin sister, Shirley, to compete in 4 winter Olympic Games. We spoke to Dr. Firth about the topic of mental health, her experience as an Indigenous athlete, and what truth and reconciliation mean to her. We also invited Dr. Chantale Lussier, a highly sought-after mental performance consultant, to be a part of this conversation. Drawing on our conversation, this article explores mental health considerations for Indigenous sport participants, and what those considerations mean for truth and reconciliation.

A conversation with Dr. Sharon Anne Firth (SAF)

SIRC: Tell me about how you got started in sport and what it did for your mental and physical health.

SAF: When my sister, Shirley, and I were first introduced to cross-country skiing in the North, we went out because it was fun and we got to meet new people, even in our community. Then it became an opportunity to travel and see the world. And both my sister and I grabbed on to it, because we came from a family of 13 and there was no way that we would ever be able to travel outside of Inuvik or the Northwest Territories.

And when we joined that sport, it taught us how to take care of ourselves, mentally and physically. It’s a sport that needs a lot of practice and imitation. And it’s important to understand why you’re doing it, what the training is all about, and what the training does for you in the long run. And when you’re in top physical condition, you feel amazing. And everything is easy and fun, and you love what you’re doing. So, it’s a healthy sport. And it’s a healthy way of keeping positive. And we really needed that.

SIRC: Why do you say that sport is something that you needed to keep healthy and positive?

SAF: You know, residential school and Indian Day School helped us in many ways, but it also destroyed us in many ways. It broke down our family unit. And some people benefited from the education, while others didn’t. I thought that I was pretty sound. I thought that I really had a strong healthy mind. But as I got older, I realized how damaged my mental health was due to the horrible, horrible, horrible beatings from the residential school and Indian Day School. And there were separations between Roman Catholic and Anglican students, and you couldn’t play with each other. The non-Indigenous people separated us and then we started finding fault in one another, whereas before we didn’t see those faults. We just saw our friends and family getting together. Even now, as Indigenous people, I think sometimes we have to work harder to be accepted. And I don’t know why. I don’t know why we have to work that hard to be accepted.

SIRC: How does it feel to be among the first Gwich’in Indigenous women, alongside your twin sister, to compete for Canada in the Winter Olympic Games?

SAF: If I go into a room, and nobody knows who I am, I deliberately don’t tell them about my career and my achievements because I want to see how I’m treated. And as soon as someone says, “Sharon’s a 4‑time Olympian,” everything changes. People look at me differently, and they treat me differently.

But not everybody’s going to make it to 4 Olympics. Not everybody’s going to be high on the podium. Not everybody’s going to get into sport. We’re not going to be good at everything. And a lot of times, I tore myself to pieces because my expectations of success were so high. When my sister and I were competing for Canada, it felt like the whole Indigenous population was on our shoulders. People watched us and because we didn’t win gold medals, maybe they thought we weren’t good enough.

So, my sister and I, we learned that, yes, we are representing our people. And it was an honour and privilege to go out there. And to always be open to talking with our people and not to push them aside, to remain humble, because they’re supporting us. And having that support from one another, our family, our communities, it helped us to achieve our potential on our own terms.

SIRC: What were some of the challenges you faced as an athlete? And how do these challenges play a role in mental health?

SAF: A lot of times when training, we didn’t have money to buy good quality food. And as poor athletes, sometimes we didn’t eat 3 square meals a day. So doing all that exercise without replacing the calories we lost, you know, it’s damaging. And it does create mental issues because you’re going to bed hungry. And I don’t know if other athletes experienced that, but I know we did.

Getting proper nutrition is a big barrier to physical and mental health for people in the North, and it can create an extra layer of stress for athletes. When we were growing up in Inuvik, all our fresh fruits and vegetables were sent up by barge and you had to eat all those foods before they went rotten. That’s less of an issue now, but food insecurity for communities in the North is still a big problem. And even down south, on the reserves there, they don’t have good water. And without clean water, you’re dead, so to speak, because then you turn to the junk food and the sugary drinks and things like that.

Another challenge is the lack of resources. In some northern communities, healthcare consists of a nursing station with 1 staff member. And that staff member might be a registered nurse or they might be a volunteer. It isn’t the same as down south. And I think the reserves are the same, they don’t have the resources.

SIRC: What can sport organizations do to support the mental wellbeing of Indigenous participants?

SAF: My sister always told me, “We love the human race.” So, let’s show it. We can’t do it ourselves; we need one another. If someone is reaching out for help, we can’t tell them to come back tomorrow and wait to see what happens. Give what you can now because who knows what tomorrow will bring?

My goal since September 30, the first National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, has been to not discriminate against anyone and to accept everyone. For me, it’s important to be as positive as I can. And I’m not always going to be positive, I’m not going to always be happy because we aren’t perfect people. You can’t expect perfection from people because we’re all imperfect. We need to re-learn and re-teach ourselves about friendship because we all want friends.

And sports and education go hand in hand. So, with mental health issues I think it’s important to be very gentle with the information you bring forward, and how we talk to all races because Canada is a multicultural country. It’s important not to discriminate, because we’re all related in one way or another. Focus on the good that you see, not on the flaws. It’s about keeping your mind, heart and words healthy.

SIRC: Do you have any final thoughts you’d like to leave with our readers?

SAF: I remember from some time back, this elderly lady told me we have to blossom where we’re planted. We’re all searching for everything in the world today, and we aren’t going to get all the right answers. And that phrase, blossom where you’re planted, it’s powerful because you have to start thinking, “this is where I’m living, so I have to make the best of it.”

And as for the word “reconciliation,” I don’t even know what that means. With truth and reconciliation, I can seriously work on the truth side. Because we all want truth. So, if we’re going to be helping, we have to be honest with ourselves, and honest with the people we’re dealing with. And sometimes it’s very frightening. It’s very frightening because you think people are going to start judging you right then and there. But we need to really focus on ourselves and what we’re offering society honestly and truthfully because people are going to make their own choice, whether it’s good or bad.

And I can’t think for anybody else. I don’t want to give something I don’t know. All I’m doing in this area is speaking from my own experience. This truth and reconciliation, it’s really confusing, and you can no longer sweep anything under the rug, because some of us don’t have rugs. So, I’m just going to end on that note of ‘we have to blossom where we’re planted.’

Insights from Dr. Chantale Lussier (CL)

SIRC: How do you think mental health is typically viewed or conceptualized in Canada?

CL: I think I’m still trying to understand and define what mental health means to me. A lot of times when we say mental health, we’re actually referring to mental illness or “dis-ease,” and I would put a little dash in the middle of that word. And what I mean by that is that we use the word mental health most often when we’re struggling, and when we’re not okay. But what does mental health look like when I’m well, or when I’m in alignment? I want to try to get away from only looking at mental health in terms of dis-ease, because even though we all struggle, I don’t think human beings are broken. And so, when we’re talking about mental health, I’m always looking for the resilience, the strength, the hope. What is it that makes us come back to life? One word that’s really important to me these days is vitality. When do I feel that life force in me? And how can I cultivate that more? And to me, that’s mental health.

And I think, especially in the Western world, and certainly in southern Canada, we tend to be very much an individualistic society. And we forget that mental health also has a collective component. Do I feel connected? Do I feel like I belong? Do I feel accepted? There are components of mental health that occur at the individual level, but I think we forget that mental health also has a social component. And when we’re thriving, it isn’t just individually, it’s also interpersonally.

SIRC: Hearing Sharon discuss some of the challenges she faced, how do you think access to necessities such as clean drinking water and adequate nutrition play a role in the mental health of Indigenous sport participants?

CL: It’s so important to hear what Sharon just talked about because there are many Canadians who don’t even have access to clean water or who struggle with food insecurities. And what do we tell athletes and coaches? Take care of your bodies. Eat healthy. And when I think of mental health, a lot of times we forget the brain is part of our bodies. So as Sharon talked about, if we aren’t even accessing, for example, good water, but we have a lot of access to pop… our blood sugar might not be consistent, our hydration levels might not feel right. And maybe our stress level is high because we don’t know what our next meal is going to be. And if we’re working in mental health fields, we can’t take for granted that 3 meals a day is the norm for everybody. We can’t take for granted that fresh fruit and vegetables are the norm for everybody. And we’ve got to really consider what’s happening at the brain health level, as well as the cognitive and emotional health of people.

SIRC: What else might we need to consider when it comes to supporting Indigenous athletes’ mental health and wellbeing?

CL: Mental health literacy is really important, and we’re learning it either formally or informally. We’re learning things every day through other people’s modeling of what is or isn’t important when it comes to mental health. For example, I grew up in a family that wasn’t perfect. There were some traumas in my family and some people who struggled with mental health. And I learned certain things about that. So, when we’re talking about barriers to mental health, the first thing we need to ask is: What did I learn growing up (whether it’s through sports, through school, or through my family, that either made it okay to talk about mental health, or that made it taboo)? And are there barriers to even asking for help? The things we learn in our families and in our society about addiction or trauma or grief stay with us. And the experiences that Sharon described with discrimination, residential school, breakdowns in family systems, intergenerational trauma… these are experiences that play into the mental health and wellness of many Indigenous athletes. This is where we must attend to and listen to the communities we want to help.

SIRC: How might the lens we use to approach mental health with Indigenous sport participants need to look different? What’s needed to make current approaches to mental health more inclusive?

CL: For me, there are 3 big things on my radar as a mental performance consultant that I need to continue to be attuned to and learn more about. The first is the idea that there are places and cultures that tend to be more individualistic, and there are places and cultures that tend to be more collectivist. Canada in general tends to be thought of as an individualistic society, and often Canadian approaches to mental health are viewed through an individualistic lens. And I could be wrong, but I don’t think many Indigenous people would view themselves and their communities in an individualistic way. I think right there, that’s where we’re missing the boat when it comes to helping people from diverse backgrounds and cultures in Canada. From cultures where the family and the social structure is such a vital part of identity, let alone mental health.

Second, I think a lot of the field of psychology has been focused on the intrapersonal. It’s been focused on the individual, and that person’s thoughts, feelings, experience and identity. And as a result, the interventions that we use to support mental health tend to be very individually focused as well. And it was only when I was exposed to couples and family systems through a counselling course that I realized mental health doesn’t have to be strictly focused on the individual. Mental health can also be looked at in terms of the couple, in terms of the family unit, in terms of a sports team. Sports teams can bolster mental health because they provide a place of belonging, connection and acceptance. But they can just as easily damage our mental health if they’re toxic, unsafe spaces. So that’s something else that’s been on my mind is that intra- versus inter-personal because as individuals, we aren’t completely disconnected from others. We live in family systems. We live in communities. We play on teams. And mental health is the stuff that happens between us, not just the stuff that happens in us.

And the third thing that’s been on my radar, and that’s been a part of my own journey as a human being, is that my training in sports psychology was extremely secular. Frankly, it wasn’t multicultural at all. And as I started to expand my own knowledge, I took a course in counseling for multiculturalism. Because it’s a multicultural world out there, and as someone who works in the areas of mental health and performance, I need to be well equipped to meet people from many different cultures. And with that, of course, comes faith. Because culture and faith, depending on where we grew up, may or may not be significant. So, when I’m working with a new client, my intake form now includes questions about culture and faith. Did they grow up practising a certain faith? And is that faith important to them? Because for some people, their spiritual life might be an intrinsic part of how they do their sport, and of how they cultivate their mental wellbeing.

SIRC: How do truth and reconciliation play a role in your work as a mental performance consultant?

CL: I’m slowly learning about what we’ve done in Canada. About residential schools. About the truth we’re barely starting to speak of. It’s such an important thing to remember, you know, when doctors take an oath, if I’m not mistaken, part of the doctor’s oath is do no harm. And I think when it comes to mental health professions, we need come back to that first and foremost. I can have the best of intentions in my heart as a practitioner, but as Sharon said, I’m a human being and I’m not going to be perfect. I need to listen and learn before I can intervene. But that requires courage for practitioners who want to help, right? Because it’s scary. I might make mistakes. I genuinely want to help my fellow human beings, but I’m not perfect. So, I always come back to how do I ensure first and foremost that I don’t harm another human being. And how can I really listen to their stories, to their needs. Because then maybe there’ll be an opportunity for me to be of genuine help.