Sport BC recognizes the importance of volunteers in amateur sport. The significant role volunteers play in their community is celebrated through Sport BC’s Community Sport Hero Awards. The award honours volunteers from Sport BC member and partner organizations who demonstrate the spirit of volunteerism through the years of dedication and commitment they have given to their sport enhancing their local community. The eight recipients will be celebrated during Sport BC’s Community Sport Hero Awards taking place on Thursday, September 14, 2023, in Victoria, BC. Congratulations to the VICTORIA Community Sport Hero Awards Recipients and thank you for all you do for amateur sport in the Greater Victoria area.

Rob Newman, President and CEO of Sport BC says, “I applaud the eight recipients of Sport BC Community Sport Hero Awards, they each believe in the transformative power of sport and are bringing their various skill sets and talents to the amateur sport organizations for which they have volunteered. Volunteering is the backbone of sport in British Columbia and these recipients are inspiring examples of the exceptional people volunteering to deliver amateur sport in the Victoria region.”

Sport & 2023 CSHA VICTORIA RECIPIENTS

Triathlon: Jacqui & Wayne Coulson

Swimming: Jeffrey Stevens

Ringette: Laura Tighe

Archery: Greg Birtwistle

Rowing: York Langerfeld

Ice Hockey Officiating: Kirk Van Helvoirt

Figure Skating: Kailee Bowman

Jacqui & Wayne Coulson

For more than 20 years, Jacqui and Wayne Coulson have officiated at community and higher-level events on the Island with Triathlon BC. Jacqui and Wayne do not hesitate to give up their time at many races each year, and they have mentored plenty of new officials and helped countless athletes. The Coulson’s are an encouragement to others entering the sport and inspire volunteerism throughout the Victoria area.

Jeffrey Stevens

Jeff’s remarkable journey with competitive swimming began over a dozen years ago when his daughters embarked on their developmental swimming journey with Pacific Coast Swimming in 2010. Jeff transitioned from supportive parent to esteemed volunteer, with pivotal roles in event management and leadership positions with Pacific Coast Swimming and Island Swimming Club. His impact as a mentor, official, and educator has left an indelible legacy within the competitive swimming community in Victoria.

Laura Tighe

If it wasn’t for Laura’s dedication and perseverance, the Greater Victoria Ringette Association would not exist. Through trials and tribulations, Laura brought a sport to a community that had no previous knowledge of it. She has successfully created opportunities for children, spaces for young adults, and a long-standing association through her dedication to sport.

Greg Birtwistle

Greg is not one to seek out recognition but is one who undoubtedly should be acknowledged. He is currently the Vice President of the Victoria Bowmen Archery Club. When Greg isn’t volunteering, he can be found building longbows which he often donates for raffles and door prizes. For over 30 years, his passion for archery and his willingness to help wherever he can has impacted many and made him a key person in the sport community.

York Langerfeld

York’s involvement in the rowing community is difficult to summarize. He’s an Umpire and on the Board for Rowing BC, a volunteer on multiple committees, a Treasurer for the Victoria Rowing Society, and a coach for UVIC’s Women’s Rowing program. He is just as likely to be at his desk hammering out financial statements and he is to be on the water, keeping athletes safe. York is someone the sport community can always count on to get things done so that others can enjoy the sport of rowing.

Kirk Van Helvoirt

Officiating for over 30 years, Kirk has volunteered for most of that time. He’s also been the lead in high performance amateur officiating development on Vancouver Island for around 15 years. He has dedicated thousands of hours of teaching, evaluating, coaching, and leading to hundreds of officials. There is not an official on Vancouver Island over the past decade that has officiated beyond their local arena that has not been impacted by Kirk’s leadership.

Kailee Bowman

Kailee has been the head coach for the Special Olympics BC – Victoria Figure Skating Program, the Head Coach Coordinator, Acting Local Coordinator, and most recently, the Local Coordinator. Throughout all her many roles, Kailee brings forward a positive inclusive mindset to make sure athletes and fellow volunteers are a priority. She has made a remarkable impact on her sport community over the years.

About Sport BC

Sport BC believes in the power of sport and is committed to building stronger communities through positive sport experiences. Our goal is to enhance and support sport participation in British Columbia ensuring everyone has the opportunity to thrive. Through our KidSport BC, BC Amateur Sport Fund, and ProMOTION Plus along with our services Sport BC Insurance, and Payroll and Group Benefits; Sport BC supports our sixty plus member organizations. Keep up to date @SportBC.

Community Sport Hero Awards Media Contact

Thursday, September 14, 2023 Allison Mailer

Coast Victoria Hotel and Marina Sport BC, VP Operations

@SportBC allison.mailer@sportbc.com

#PoweringSport 778-839-8576

PV:

PV:  It really annoys me that people think the only way to get people to volunteer is to get down on our knees and say “Please do me a solid. Do it for the kids!” Firstly, that makes it seem like it’s a really bad thing. If we’re desperately begging people to do it, then it’s not sounding particularly desirable. Secondly, if you’ve guilt tripped people into volunteering, they’re more Iikely to put in the minimum effort because you’ve kind of forced them into it.

It really annoys me that people think the only way to get people to volunteer is to get down on our knees and say “Please do me a solid. Do it for the kids!” Firstly, that makes it seem like it’s a really bad thing. If we’re desperately begging people to do it, then it’s not sounding particularly desirable. Secondly, if you’ve guilt tripped people into volunteering, they’re more Iikely to put in the minimum effort because you’ve kind of forced them into it.  The COVID‑19 pandemic has presented sport organizations with an opportunity to ask and answer important questions, including how to adapt sport programming to meet stakeholders’ needs while adhering to public health regulations (Own the Podium, 2020; Patton, 2020). Given the pandemic, a research team at Brock University and the University of Ottawa sought the perspectives of 28 Canadian sport-sector stakeholders from the grassroots level to national sport organizations (NSOs). Their conversations revealed a priority shift in 1 of 2 ways about evaluation practices:

The COVID‑19 pandemic has presented sport organizations with an opportunity to ask and answer important questions, including how to adapt sport programming to meet stakeholders’ needs while adhering to public health regulations (Own the Podium, 2020; Patton, 2020). Given the pandemic, a research team at Brock University and the University of Ottawa sought the perspectives of 28 Canadian sport-sector stakeholders from the grassroots level to national sport organizations (NSOs). Their conversations revealed a priority shift in 1 of 2 ways about evaluation practices: Specific individuals within an organization are sometimes tasked with evaluation. However, applying a team approach that includes diverse stakeholders throughout the process can help to formalize evaluation, monitor activities, and ensure evaluation is aligned with organizational goals. An evaluation team should involve sport stakeholders at different levels, including individuals involved in on-the-ground program delivery, in managerial roles, and external to the organization.

Specific individuals within an organization are sometimes tasked with evaluation. However, applying a team approach that includes diverse stakeholders throughout the process can help to formalize evaluation, monitor activities, and ensure evaluation is aligned with organizational goals. An evaluation team should involve sport stakeholders at different levels, including individuals involved in on-the-ground program delivery, in managerial roles, and external to the organization. Without evaluative thinking, an evaluation may end up being superficial and without intention. Thus, by using evaluative thinking, the evaluation team members can keep themselves accountable for the questions they ask, the activities they engage in, and the way they interpret and communicate findings. In this way, evaluation becomes well-planned, activities are maintained, and the results support program improvement and continuity.

Without evaluative thinking, an evaluation may end up being superficial and without intention. Thus, by using evaluative thinking, the evaluation team members can keep themselves accountable for the questions they ask, the activities they engage in, and the way they interpret and communicate findings. In this way, evaluation becomes well-planned, activities are maintained, and the results support program improvement and continuity. Storytelling can be especially empowering when told through the voices of stakeholders. For instance, coaches may share stories about how they delivered specific program practices, like teaching athletes about the value of team building. Sharing such stories could positively affect the athletes. For example, encouraging them to take initiative by mentoring younger players. An athlete could also share how their role as a captain of a soccer team helped them learn the value of being a leader in their community. By weaving data and statistics into these stories, the narrative can be placed within a program’s greater context.

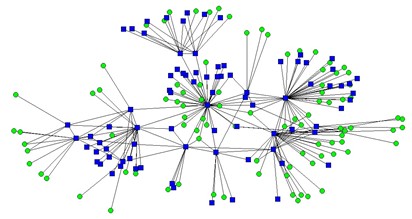

Storytelling can be especially empowering when told through the voices of stakeholders. For instance, coaches may share stories about how they delivered specific program practices, like teaching athletes about the value of team building. Sharing such stories could positively affect the athletes. For example, encouraging them to take initiative by mentoring younger players. An athlete could also share how their role as a captain of a soccer team helped them learn the value of being a leader in their community. By weaving data and statistics into these stories, the narrative can be placed within a program’s greater context. Including students and volunteers in program evaluations has several benefits for sport organizations. For instance, graduate students may have knowledge of frameworks and tools to guide evaluation practices and have the training to produce rigorous and evidence-based results for the sport organization. Additionally, students have access to research papers that are typically behind paywalls for the public, which may help to facilitate specific evaluation methods, such as the use of validated questionnaires.

Including students and volunteers in program evaluations has several benefits for sport organizations. For instance, graduate students may have knowledge of frameworks and tools to guide evaluation practices and have the training to produce rigorous and evidence-based results for the sport organization. Additionally, students have access to research papers that are typically behind paywalls for the public, which may help to facilitate specific evaluation methods, such as the use of validated questionnaires.  The Canadian Disability Participation Project (CDPP) is an alliance of university, public, private and government sector partners working together to enhance participation among Canadians with physical disabilities across employment, mobility, and sport and exercise sectors. The CDPP involves nearly 50 cross-sector partners that engage in community-based projects. This leads to resources and publications that partners can use and disseminate.

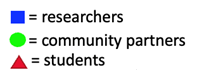

The Canadian Disability Participation Project (CDPP) is an alliance of university, public, private and government sector partners working together to enhance participation among Canadians with physical disabilities across employment, mobility, and sport and exercise sectors. The CDPP involves nearly 50 cross-sector partners that engage in community-based projects. This leads to resources and publications that partners can use and disseminate.

True Sport is a series of programs and initiatives designed to leverage the benefits of sport through a platform of shared values and principles. In 2018, I was part of a research team that partnered with True Sport to conduct a pragmatic evaluation of the True Sport initiatives (Lawrason et al., 2021). The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) Framework (Glasgow et al., 1999) informed the evaluation. The RE-AIM Framework provides a guide of what to evaluate in a program beyond effectiveness. Learn more about

True Sport is a series of programs and initiatives designed to leverage the benefits of sport through a platform of shared values and principles. In 2018, I was part of a research team that partnered with True Sport to conduct a pragmatic evaluation of the True Sport initiatives (Lawrason et al., 2021). The Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance (RE-AIM) Framework (Glasgow et al., 1999) informed the evaluation. The RE-AIM Framework provides a guide of what to evaluate in a program beyond effectiveness. Learn more about