Centralizing the voice of the athlete is a critical step in ensuring Safe Sport is realized. This was the primary theme of our talks on the panel “The future of safe sport: Hooked on hope not fishing for problems” at the 2023 Sport Canada Research Initiative (SCRI) conference.

An athlete-centered view of sport, while not a new concept, remains an area of deficiency within management and governance models in sport. This includes athletes’ contributions to policy formation, environmental design, and sport services. Supporting the safe sport movement also requires a deep dive into what athletes experience, their beliefs and the values held as most important which they feel is driving behaviour (both good and bad). As the Canadian sport system grapples with several changes, it is even more critical that the athlete voice comes to the table to be a part of shifting the culture and understanding the various problems while working towards the ideals of safe sport.

An athlete-centered view of sport, while not a new concept, remains an area of deficiency within management and governance models in sport. This includes athletes’ contributions to policy formation, environmental design, and sport services. Supporting the safe sport movement also requires a deep dive into what athletes experience, their beliefs and the values held as most important which they feel is driving behaviour (both good and bad). As the Canadian sport system grapples with several changes, it is even more critical that the athlete voice comes to the table to be a part of shifting the culture and understanding the various problems while working towards the ideals of safe sport.

In Nova Scotia for instance, the voice of the athlete has been an integral piece in policy and safe sport education. In 2021, Sport Nova Scotia held an Athlete Safe Sport Summit to engage athletes throughout the province to discuss their values and to learn what was important to them. Following the Summit, an Athlete Advisory Committee (AAC) was created and, over the last few years, the AAC has been instrumental in creating safe sport education tools and resources which includes a series of podcasts focused on athlete mental health. This diverse group of athletes representing all levels of sport, from across the province, has demonstrated a commitment to fostering the values of “safe, welcoming, and inclusive” sport environments in Nova Scotia.

In addition to the AAC, and with the goal of ensuring athletes’ values are present in fostering safe sport, Sport Nova Scotia, in partnership with the Canadian Centre for Ethics in Sport (CCES) and the Canadian Sport Institute Atlantic (CSIA), created the Nova Scotia True Sport Athlete Ambassador Program (NSTSAAP). In 2020, the partners began working together with the understanding that positive values must be committed to and prioritized throughout sport in Canada. It was recognized that when sport is values-based, it has the power to positively influence behaviour and create a culture that instils character, strengthens communities, and increases opportunities for excellence. The partners choose to champion True Sport as their approach to values-based sport, an initiative of the CCES. Values-based sport places values at the heart of all policies, practices, and programs to ensure that positive experiences foster a culture of good sport in the long term.

In practice, the partners created the NSTSAAP and over the last 3 years have engaged a diverse cohort of athletes each year who use their voices and their passion to share True Sport. These athletes are nominated by their Support4Sport vip coach, a CSI Atlantic program. This program was created to recognize the contribution of coaches in communities across Nova Scotia. vip is not a certification or requirement, but rather a proactive opportunity for coaches to continue to excel in ethical leadership.

The NSTSAAP nomination and selection process is based upon the athlete’s activation of True Sport on and off the field of play. The goal of the NSTSAAP is to increase awareness, understanding and engagement of values-based sport. The NSTSAAP is the first of its kind in Canada and is about to announce its Year 3 True Sport Ambassadors.

The NSTSAAP nomination and selection process is based upon the athlete’s activation of True Sport on and off the field of play. The goal of the NSTSAAP is to increase awareness, understanding and engagement of values-based sport. The NSTSAAP is the first of its kind in Canada and is about to announce its Year 3 True Sport Ambassadors.

Placing values at the core of decision-making is not easy work, especially in a sport system that has placed a considerable emphasis on podiums and winning. However, doing so allows sport organizations and their leaders to reflect on the lived experience of their constituents and to emphasize the process while having an eye on organizational and competition excellence. To do this well, collaboration and communication must remain constant to help address and prevent maltreatment. A values-based approach involves understanding the culture and the perspectives of those most affected creating a need to have athletes help create comprehensive policies, training and support systems needed to shift the culture.

Coaches and administrators are key stewards of a move toward safer sport. They are entrusted with the responsible management and administration of a safe sporting environment through the development, implementation and reinforcement of policy and behavioural practice in their organizations and on their teams. High performance athletes

Coaches and administrators are key stewards of a move toward safer sport. They are entrusted with the responsible management and administration of a safe sporting environment through the development, implementation and reinforcement of policy and behavioural practice in their organizations and on their teams. High performance athletes

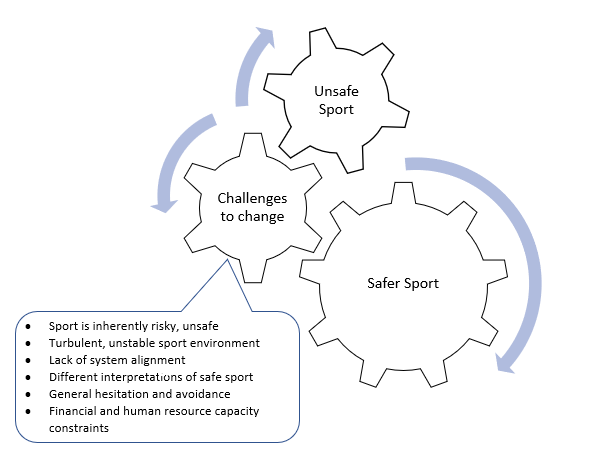

Finally, the leaders highlighted how financial and human resource capacity constrained their ability to develop and implement educational, policy, and reporting practices related to safe sport. One leader summed up the issue as a matter of the organization’s survival:

Finally, the leaders highlighted how financial and human resource capacity constrained their ability to develop and implement educational, policy, and reporting practices related to safe sport. One leader summed up the issue as a matter of the organization’s survival: